I spent the most formative time of my life, the years 1931-33, as a Gymnasiast and would-be Communist militant, in the dying Weimar Republic. Last autumn I was asked to recall that time in an online German interview under the title ‘Ich bin ein Reiseführer in die Geschichte’ (‘I am a travel guide to history’). Some weeks later, at the annual dinner of the survivors of the school I went to when I came to Britain, the no longer extant St Marylebone Grammar School, I tried to explain the reactions of a 15-year-old suddenly translated to this country in 1933. ‘Imagine yourselves,’ I told my fellow Old Philologians, ‘as a newspaper correspondent based in Manhattan and transferred by your editor to Omaha, Nebraska. That’s how I felt when I came to England after almost two years in the unbelievably exciting, sophisticated, intellectually and politically explosive Berlin of the Weimar Republic. The place was a terrible letdown.’

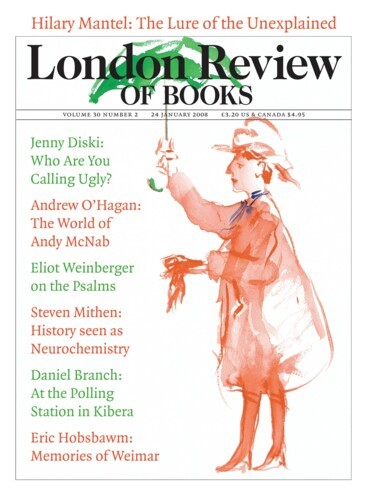

The cover of Eric Weitz’s excellent and splendidly illustrated Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy brings back memories.* It shows the old Potsdamer Platz long before its transformation into a ruin at the hands of Hitler and into Disneyland architecture in the reunified Germany. Not that daytime cafés full of men in trilbys like my uncle were the habitat of Berlin teenagers. We were more likely to think of boats on the Wannsee, a place not yet associated with planned genocide.

It is hard to remember, though Hitler made it the staple of his rhetoric in the ironic plethora of voting that took place in its last year, that the republic lasted only 14 years, and of these just six, sandwiched between a murderous birth-period and the terminal catastrophe of the Great Slump, had a semblance of normality. The massive international interest in it is largely posthumous, the consequence of its overthrow by Hitler. It was primarily this that raised the question of Hitler’s rise to power and whether it could have been avoided, questions that are still debated among historians. Weitz concludes, with many others, that ‘there was nothing inevitable about this development. The Third Reich did not have to come into existence,’ but his own argument drains most of the meaning out of this proposition. In any case, it was clear to those of us who lived through 1932 that the Weimar Republic was on its deathbed. The only political party specifically committed to it was reduced to 1.2 per cent of the vote and the papers we read at home debated what room there was in politics for its supporters.

It was also Hitler who produced the community of refugees who came to play a disproportionately prominent part in their countries of refuge and to whom Weimar’s memory owes so much. Certainly they were far more prominent, except in the world of ballet, than the much larger post-1917 Russian emigration. They may have made little impact on the old entrenched professions – medicine, law – but their impact on more open fields, and eventually on science and public life, was quite remarkable. In Britain émigrés transformed art history and visual culture, as well as the media through the innovations of Continental publishers, journalists, photographers and designers.

For the basic achievements of the Weimar Republic and the reasons non-Germans take an interest in it are not political but intellectual and cultural. The word today suggests the Bauhaus, George Grosz, Max Beckmann, Walter Benjamin, the great photographer August Sander and a number of remarkable movies. Weitz picks out six names: Thomas Mann, Brecht, Kurt Weill, Heidegger and the less familiar theorist Siegfried Kracauer and the artist Hannah Höch. One could as easily add, say, Carl Schmitt on the (rare) intellectual right, Ernst Bloch on the far left and the great Max Weber in the middle.

In 1933 only Thomas Mann and a few films had made much of a stir beyond the narrowest of niche-publics outside Central Europe, and possibly a small homosexual subculture which discovered the attractions of Berlin in the final Weimar years. Mann was, of course, an established master even before 1914. He won the Nobel Prize in 1929, though not for his Weimar masterwork, The Magic Mountain, so much as the more ancient Buddenbrooks. But who in England had heard of Franz Marc, whose blue horses adorned the corridor of my Gymnasium until the new regime removed them, together with our republican headmaster?

At that time Paris was the unquestioned capital of the visual arts, Vienna still the native home of both heavy and light music. German was not widely spoken in the West outside the transatlantic diaspora or read outside classical scholarship. Even today only German speakers recognise Brecht not just as a dramatist but as one of the great 20th-century lyric poets. About the only branch of Weimar literature that broke out of the Central European enclosure was the anti-war fiction of the late 1920s, headed by Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front. Naturally, it was filmed by Universal, the only Hollywood studio headed by a native German.

What, looking back, was so characteristic about the culture of a shortlived German republic that nobody had really wanted and most Germans accepted as faute de mieux at best? Every German had lived through three cataclysmic experiences: the Great War; the genuine, if abortive German revolution which overthrew the defeated Kaiser’s regime; and the Great Inflation of 1923, a brief manmade catastrophe that suddenly made money valueless. The political right, traditionalist, anti-semitic, authoritarian and deeply entrenched in the institutions carried over from the Kaiser’s Reich (I still remember the title of Theodor Plivier’s 1932 book, The Kaiser Went, the Generals Remained), refused the republic totally. It regarded Weimar as illegitimate, the Versailles Treaty as an undeserved national shame, and aimed at getting rid of both of them as soon as possible.

But almost all Germans, including the Communists, were passionately against Versailles and the foreign occupiers. I can still recall as a child seeing from the train the French flag flying on Rhineland fortresses, with a curious sense that this was somehow unnatural. Being both English and Jewish (I was ‘der Engländer’ at school) I was not tempted into the German nationalism of my schoolfriends, let alone into Nazism, but I could well understand the appeal of both to German boys. As Weitz shows, the authoritarian right was always the main danger both politically and, through their persistent and popular hostility to ‘Kulturbolschewismus’, culturally.

The major centrist thinkers – Mann, Max Weber, Walther Rathenau, none of them instinctive democrats, but urged on by fear of the gun-happy right – managed to justify a democratic republic as the necessary successor to an unrestorable Reich. So, of course, did the main parties of the system: the majority Social Democrats, who had not actually wanted the Kaiser to go, and the Catholic Centre, transformed by the revolution from a confessional pressure group into a government party. Beyond these the political left, shaped largely by revulsion against the Great War, shock at the failed revolution of 1918, and hatred of the old ruling class that survived it so well, was no less rejectionist than the right. Joined by half of the anti-war independent breakaway from the Social Democratic Party, the Communist Party acquired a mass base of intransigent working-class opposition. Large enough to block the fashioning of a lasting non-right Weimar regime, this left did not wish to contribute anything to its practical politics except disgust.

For understandable reasons creative artists, radicalised by the horrors of war and the hope and fury left behind by lost revolution, were attracted to it; indeed, there are Weimar figures whose lasting achievement rests primarily on the force of their distaste for the republic. Even genuine high talents like George Grosz and Kurt Weill ceased to be very interesting when, after 1933, they arrived in the US and felt at ease. This was even more the case with lesser talents among the Expressionist writers and artists moved by pain and outrage to find temporarily memorable ways to express humourless emotion at the top of their voices. It was partly against these that Weimar found the nearest thing to its own voice after the Great Inflation, hard-nosed, unsentimental, passionate but cabaret-cool, in the ‘Neue Sachlichkeit’ (‘New Sobriety’). For me, Weimar still speaks now, as it did in 1932, with the voice of Mahagonny and The Threepenny Opera, of Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, of the underrated Erich Kästner, or of the pawky political chansons of Erich Weinert.

But Weimar was more than a German phenomenon. Weitz, whose book is a superb introduction to its world, probably the best available, gets so many things about it right: not least the Berlin-centredness of Weimar culture, as distinct from pre-1914 Germany with its flourishing artistic centres in Munich and Leipzig. Yet he underestimates its role as a crucible for what after 1917 was the major generator of intellectual and artistic innovation: post-revolutionary Central and Eastern Europe. The prestige of Paris, ‘capital of the 19th century’, obscured the fact that it no longer had major innovations to offer between the wars except for Surrealism, itself largely derived from the multinational Dada of the Zurich Central European refugees.

With its seven thousand-plus periodicals, 38,000 books (in 1927) and the most formidable movie industry outside Hollywood, Germany was a vast market. With the fall of the Habsburg Empire it naturally absorbed the large surplus talent of what remained of Austria. Where would Weimar films be without Vienna, without Fritz Lang, G.W. Pabst, Wilder, Preminger or, for that matter, Peter Lorre? Its stable of stars – Conradt Veidt, Emil Jannings, Marlene Dietrich, Elisabeth Bergner – were trained under the Viennese Max Reinhardt, the chief influence on the German-language theatre business. In Berlin my family, themselves migrants from Vienna, went on living a social life largely centred on other Austrian expatriate relatives and friends.

For different but equally obvious reasons Germany was Russia’s major window to the west. Berlin was both the main centre of the anti-Soviet emigration and the first stop on the western excursions of the new Soviet intellectuals and artistic revolutionaries, some of whom published a multilingual review there. Nor indeed should we forget that, in vain expectation of the German revolution, the official language of the Comintern was not Russian but German.

Inevitably, this cultural mix fertilised Weimar and eventually Western culture. The Bauhaus was throughout its existence a collective of Germans, Austro-Hungarians, Russians, Swiss and Dutch. It is characteristic that what amounted to a ‘Constructivist international’, as John Willett described it, was set up by a collection of Hungarians, Dutch, Belgians, Romanians, Soviet Russians and Germans at a meeting in Weimar with prospective headquarters in Berlin. This was the culture that German émigrés imported into their countries of refuge.

The central international role of Weimar Germany in 20th-century science is equally easy to overlook. Einstein and Max Planck gave glory to Berlin, while Göttingen under Max Born was, with Cambridge, the catalyst of the revolution of quantum mechanics, the ‘boy physics’, whose communal idiom, like the language of international Communism, was German. Heisenberg, Pauli, Fermi, Oppenheimer, Teller all worked or studied there. The most dramatic evidence for the centrality of Weimar Germany are the 15 science Nobel Prizes won by Germans in its 14 years, a number it took the subsequent fifty years to equal.

This was the last time Germany was at the centre of modernity and Western thought. It might have held out better if the Weimar Republic had been followed not by Hitler’s wrecking crew but by a more traditional reactionary government. Yet in retrospect this option was as unreal as was the prospect of stopping Hitler’s rise by a comprehensive anti-Fascist union. The fact is that no one, right, left or centre, got the true measure of Hitler’s National Socialism, a movement of a kind that had not been seen before and whose aims were rationally unimaginable. Not even his intended victims fully recognised the danger. After the summer election of 1932 which left the Nazis as much the largest party, but short of a majority, the (Jewish) editor of the Tagebuch, a left-liberal weekly we took at home, published an article whose headline struck me even then as suicidal. I still see it before me: ‘Lasst ihn heran!’ (‘Why not let him in!’) A few months later, with very different intentions, the reactionaries around the aged President Hindenburg manoeuvred Hitler into office thinking that he could be controlled.

All attempts to make the Weimar Republic look more firmly established and stable, even before the world economic cataclysm broke its back, are historical whistling in the dark. It moved briefly through the debris of a dead but unburied past towards a sudden but expected end and an unknown future. For our parents it promised only an unrecoverable past, while we dreamed of great tomorrows; my ‘Aryan’ schoolmates in the form of a national rebirth, Communists like myself, as the universal revolution initiated in October 1917.

Even its few years of ‘normality’ rested on the temporary quiescence of a volcano that could have erupted at any time. The great man of the theatre, Max Reinhardt, knew this. ‘What I love,’ he said, ‘is the taste of transience on the tongue – every year might be the last.’ It gave Weimar culture a unique tang. It sharpened a bitter creativity, a contempt for the present, an intelligence unrestricted by convention, until the sudden and irrevocable death. Moments when one knows history has changed are rare, but this was one of them. That is why I can still see myself walking home from school with my sister on the cold afternoon of 30 January 1933, reflecting on what the news of Hitler’s appointment as chancellor meant. A few days later someone brought the duplicating machine of the SSB, my Communist schools organisation, to store under my bed. They thought it would be safer in the flat of a foreigner. But from now on nowhere was safe. Still, it was a strange and wonderful time in which to discover oneself and the world in a Berlin that looked like the potential capital of the 20th century, until the barbarians took over. When I go there today, I still feel it has never recovered from 1933.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.