After the death of Henry James’s father in 1882, his sister-in-law Catharine Walsh, better known as Aunt Kate, burned a large quantity of the family papers, including many letters between Henry James senior and his wife. Henry James himself in later life made a number of bonfires in which he destroyed a great quantity of the letters he had received. He often added an instruction to the letters he wrote: ‘Burn this!’ To one correspondent, he wrote: ‘Burn my letter with fire or candle (if you have either! Otherwise, wade out into the sea with it and soak the ink out of it).’ In two of his stories, ‘The Aspern Papers’ and ‘Sir Dominick Ferrand’, valued letters are turned to illegible ashes – ‘as a kind of sadism on posterity’, in the words of his biographer Leon Edel. James was fully alert to the power of letters, having paid close attention to the published correspondence of Balzac, Flaubert and George Sand, and alert to the power of editors. After reading Sidney Colvin’s edition of the letters of his friend Robert Louis Stevenson, he wrote: ‘One has the vague sense of omissions and truncations – one smells the thing unprinted.’

In the years after James’s death, his family in the United States was concerned about his reputation, especially about what Edel called his ‘relaxed homoerotism’; thus they refused Hendrik Andersen, whom, as Edel put it, James ‘loved in so troubled a way’, the right to publish James’s letters to him, and these have appeared only in recent years in a bilingual Italian edition, Amato Ragazzo, edited by Rosella Mamoli Zorzi, and also in Letters to Younger Men, edited by Susan Gunter and Steven Jobe.

The first letters by James to be published came in two volumes, overseen by the James family and edited by Percy Lubbock; they contained 403 letters and appeared in 1920, just four years after the novelist’s death. Lubbock found Mrs William James, the formidable widow of Henry James’s elder brother, moving ‘in a cloud of fine discretions and hesitations and precautions’. She disliked Edith Wharton ‘thoroughly – and morbidly’, as Edel put it, and this meant that Wharton or anyone else deemed disreputable could not be involved in any aspect of the estate. Miss Bosanquet, James’s highly intelligent final amanuensis, thought this a pity and recorded in her diary that Lubbock ‘joined with me in a regret that Mrs Wharton hadn’t been left in charge. He feels that it’s awfully difficult to offer advice to people like the Jameses and yet they do need some very badly!’ The text of Lubbock’s two volumes was gone over by three of William James’s children and by their mother. ‘The family scrutiny was thorough,’ Edel wrote.

As the children of William James, they had been brought up by their father to believe that their Uncle Henry in England was slightly silly, but now, as Harry James, William’s son, read these letters he was deeply impressed at their tone and their gravity. He wrote to his sister Peggy:

It will, I rather think, make Uncle Henry count very much more than he did already. For it’s full of literature as well as character. In fact I suspect that these letters will become, in the history of English literature, not only one of the half-dozen greatest epistolary classics, but a sort of milestone – the last stone of the age whose close the Great War has marked. They are a magnificent commentary on the literary life of his generation, and they’re done in a style which will never be used naturally again.

In the years that followed Harry James was contacted by many people who had bundles of letters from his uncle. Having allowed two slim volumes of these to appear, both of which he came to dislike, he was hesitant thereafter to grant permission for any more collections. Even as late as 1955, when Edel edited a Selected Letters, his work was still overseen by the family. ‘I remember removing a letter dealing with Guy Domville from the Selected Letters,’ Edel wrote, ‘because Billy James’ – another nephew – ‘found it too sad.’ Between 1974 and 1984 Edel published a four-volume edition that included 1100 letters, noting that ‘the large James archives in many libraries will provide opportunities for amplification and further collections in the years to come.’

In 1999, when Philip Horne edited Henry James: A Life in Letters, which remains the best single selection of James’s letters – the greatest hits, all 296 of them, superbly annotated and put in context – he pointed out that half of the letters he had included had not been published before. He estimated that there are between 12,000 and 15,000 letters by James in existence and suggested that many more may still be in private hands (he calculated that James may have written as many as 40,000 letters in his lifetime, many of them now lost). Some further unpublished letters had by then appeared in other editions, notably a single volume of letters between Henry and his brother William, and another single volume of letters between Henry and Edith Wharton. Jobe and Gunter, in their ‘Online Calendar of Henry James’s Letters’, updated in 1999, listed the letters they could locate: they were scattered in more than 200 books and journals, with the originals in 140 repositories and private collections.

It was obvious that a collected edition of James’s letters was needed. The project was first discussed by scholars in the early 1990s. This was made easier by the fact that, as the editors state in their general introduction to Volume I of the Complete Letters,

Leon Edel was at the very end of his career and exerted far less control over access to and publication permission for Henry James’s letters than when he was younger. The executorship of the James papers had been passed from Alexander R. James to his daughter, Bay James, following Alexander James’s death. Whereas some of her predecessors, at times at Edel’s urging, had limited full access to and publication permission for Henry James’s letters, Bay James encouraged open access and full permission.

The first two volumes, which cover James’s correspondence from his earliest known letter through to 1872, when he was 29, contain 161 letters, of which 52 are published for the first time. The final edition of the letters – 10,423 are in the editors’ hands, but more are expected to come to light – will be in more than 140 volumes.

These two volumes are dominated by the James family’s European wanderings, and then by Henry James’s first visit alone to Europe, especially his travels in England and Italy. They throw much light on his relationship with his family and his country of birth while at the same time helping us towards some understanding of his health problems, such as they were. Some of the letters from Italy are small masterpieces of description; they are alert and sensitive and full of astute judgments. Sometimes, too, James is funny, irreverent and outspoken, especially in his letters to his family but also to literary friends from Newport and Boston such as Thomas Sergeant Perry and Charles Eliot Norton.

To Norton on Germans, for example: ‘Such men – such women – such children! … Even the comparatively good-looking ones suffer from the ugliness of the others & are injured by the hideous contagion.’ To his brother William on Venetians: ‘In the narrow streets, the people are far too squalid & offensive to the nostrils, but with a good breadth of canal to set them off & a heavy stream of sunshine to light them up, as they go pushing & paddling & screaming – bare-chested, bare-legged, magnificently tanned & muscular – the men at least are a very effective lot.’ To his sister, Alice, on Pope Pius IX: ‘When you have seen that flaccid old woman waving his ridiculous fingers over the prostrate multitude & have duly felt the picturesqueness of the scene – & then turn away sickened by its absolute obscenity – you may climb the steps of the Capitol & contemplate the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius.’ To his father: ‘When the Pope, clad in shining robes crept up to the altar & in the midst of that dazzling shrine of light, possessed himself of the Host & raised it aloft over the prostrate multitudes, I got a very good look at him by poking up my head & confronting that terrible toy.’ To Alice on the view from St Peter’s in Rome: ‘I’m sure I saw one of the pontifical petticoats hanging out to dry.’ To William on the Italian past: ‘I conceived at Naples a tenfold deeper loathing than ever of the hideous heritage of the past – & felt for a moment as if I should like to devote my life to laying railroads & erecting blocks of stores on the most classic & romantic sites.’ To William on the women in Malvern: ‘I am tired of their plainness & stiffness & tastelessness – their dowdy heads, their dirty collars & their linsey woolsey trains.’

These letters were written before James developed his views on the thinness of the American experience, before his attempts to justify his own exile in England, before his efforts over many years to soak up, for the sake of his fiction, the atmosphere in France and Italy. In 1860, at the age of 17, he wrote from Bonn to Thomas Sergeant Perry in the sort of patriotic tone that he would satirise more than forty years later in The Ambassadors: ‘I think that if we are to live in America it is about time we boys should take up our abode there; the more I see of this estrangement of American youngsters from the land of their birth, the less I believe in it. It should also be the land of their breeding.’ Seven years later he wrote again to Perry:

One feels – I feel at least, that he [Sainte-Beuve] is a man of the past, of a dead generation; and that we young Americans are (without cant) men of the future… We are Americans born – il faut en prendre son parti. I look upon it as a great blessing; and I think that to be an American is an excellent preparation for culture.

Five years later, he wrote to Charles Eliot Norton: ‘I exaggerate the merits of Europe. It’s the same world there after all & Italy isn’t the absolute any more than Massachusetts. It’s a complex fate, being an American, & one of the responsibilities it entails is fighting against a superstitious valuation of Europe.’

His valuation of Europe may have ended as an artistic one, but its allure, at least in these early years, may have been much simpler: it was a beautiful way of getting away from his family. These letters make clear, more than anything, how necessary that was, and how difficult. Despite his father’s interest in his schooling, it was obvious to him, even at the age of 16, that he was not being prepared for a profession, or for anything much at all. He wrote to Perry while briefly at school in Geneva: ‘The School is intended for preparing such boys as wish to be engineers, architects, machinists “and the like” for other higher schools, and I am the only one who is not destined for either of the useful art[s] or sciences, although I am I hope for the art of being useful in some way.’ The following year he wrote to Perry from Bonn about the family’s return to Newport: ‘I have not the remotest idea of how I shall spend my time next winter … I wish, although I’ve no doubt it is a very silly wish, that I were going to college.’

His problem was that he had nothing to do. This led to intense periods of reading and writing, but it also led to his needing an alibi as he grew into his twenties, something with which he could justify himself and which would also match his parents’ needs. His famous bad back thus arose from a malady more serious perhaps than an actual physical injury, the malady of being a member of the James family with no escape route. By 1867, the question of James’s back and other mysterious illnesses was appearing with regularity in his letters, slowly becoming an excuse for him to be sent to Europe, or at least somewhere else. In November he wrote to William from the family home in Cambridge, Massachusetts:

It is plain that I shall have a very long row to hoe before I am fit for anything – for either work or play … An important element in my recovery, I believe, is to strike a happy medium between reading & social relaxation. The latter is not to be obtained in Cambridge – or only a ghastly simulacrum of it. There are no ‘distractions’ here.

Once in Europe, he made sure to pepper each letter home in which he told of the sights he saw with accounts of the state of his condition, some of them very vague. From London in March 1869 he wrote to his sister: ‘There is no sudden change, no magic alleviation; but a gradual & orderly recurrence of certain phenomena which betray the slow development of such soundness as may ultimately be my earthly lot.’ To William he wrote soon afterwards: ‘I feel every day less & less fatigue. I made these long recitals of my adventures in my former letters only that you might appreciate how much I am able to do with impunity … I mentioned all the people & things I saw, without speaking of the corresponding intervals of rest, which of course have been numerous & salutary.’ From Malvern, where he had gone to take the waters, he wrote to William again a month later: ‘The place is unfortunately built up & down hill & whenever one goes out it is always (in some degree) a perpendicular trudge – which for a man with my trouble is a circumstance to be regretted.’

In this letter, James made clear what one of the problems really was, having hinted at it in an early letter to his mother. He was plagued with constipation. Soon, however, as things began to improve, he told William that he ‘had a movement every day for a month – & at Oxford two daily’. But as soon as he reached the Continent, things grew worse. From Florence he wrote in October: ‘I may actually say that I can’t get a passage. My “little squirt” has ceased to have more than a nominal use. The water either remains altogether or comes out as innocent as it entered.’ Pills he took did not help, he wrote again, they brought ‘a species of abortive diarrhoea. That is I felt the most reiterated & most violent inclination to stool, without being able to effect anything save the passage of a little blood.’ He saw a doctor who ‘examined them [his bowels] (as far as he could) by the insertion of his finger (horrid tale!) & says there is no palpable obstruction. He seemed surprised however that I haven’t piles; you see we have always something to be grateful for.’ At the end of the letter, he wrote: ‘Having opened up the subject at such a rate, I shall of course keep you informed – To shew you haven’t taken this too ill, for heaven’s sake make me a letter about your own health – poor modest flower!’

At this stage Henry James was 26 and his brother 28. They would both live to be old, remaining vigorous, active and healthy all of their lives, dying eventually from the same type of heart disease. In April that same year, in a letter from Malvern, Henry James wrote to William: ‘Of course I have been sorry to think that you have been unable to write before by reason of your back & have greatly missed hearing from you.’ Illness within the James family was like money in some families, or worldly success or religious devotion in others. It was discussed in hushed and reverent tones, and those who did not benefit from it won no brownie points. William and Henry were lucky; they knew how far to go with it, how to refer to it enough but not too much; they understood how much to invent and how much to make of what was real. Unfortunately, Alice, their sister, who all her life made illness into a mysterious fine art, knew simply that she would need to be ill to survive her father’s erratic, chattering presence and her mother’s suffocating and controlling care, but she did not know how to stop it when it was not necessary as her two elder brothers did.

Thus Henry James’s constipation could be described by himself in detail as well as his position as someone who, because of his back, ‘shall certainly never get beyond having to be minutely cautious’. When William wanted to be nasty, as he often did, it was Henry’s back he went for. In June 1869, for example, he wrote: ‘The condition of your back is totally incomprehensible to me.’ But Henry managed always to dramatise his plight, mentioning on his return to Malvern symptoms that were ‘powerful testimony to the obstinacy of my case’ and later his ‘invalidism’, his ‘slowly crawling from weakness & inaction & suffering into strength & health & hope’. When, at one point in his European sojourn, Henry’s general condition seemed to get worse, he wrote to his father about himself as though he were translating from the heightened language of a Greek text: ‘Don’t revile me & above all don’t pity me … Dear father, if once I can get rid of this ancient sorrow I shall be many parts of a well man.’ He ended the letter by suggesting that there was a family pool of illness, or a seesaw on which they all sat waiting their turn on top. ‘I have invented for my comfort a theory that this degenerescence of mine is the [the word ‘the’ is then crossed out] a result of Alice & Willy getting better & locating some of their diseases on me – so as to propitiate the fates by not turning the poor homeless infirmities out of the family. Isn’t it so? I forgive them & bless them.’

He did not stop. In letter after letter to his parents, to William and to Alice, he remembered to mention the poor state of his health. He even tried it out on his friend Grace Norton, the sister of Charles Eliot Norton. Sometimes, when he had been giving breathless descriptions of places seen and excursions made, you realise that he had best mention it soon or they will send for him or stop believing him. In some cases it reads like an afterthought. At other times it is like an excuse. When he was accused of spending too much money, for example, he wrote: ‘My being unwell has kept me constantly from attempting in any degree to rough it.’ When he wished to travel further, spending even more money, it was his health he gave as his motive. From London he wrote to his father attempting to justify this urge:

When I left Malvern, I found myself so exacerbated by immobility & confinement that I felt it to be absolutely due to myself to test the impression which had been maturing in my mind, that a certain amount of regular lively travel would do me more good than any further treatment or further repose … I have now an impression amounting almost to a conviction that if I were to travel steadily for a year I would be a good part of a well man.

And in case that was not enough, he had to make them believe that he missed them. From London in March 1869 he wrote: ‘What is the good of having a mother – & such a mother – unless to blurt out to her your passing follies & miseries … Yes – I confess it without stint or shame – I am homesick – abjectly, fatally homesick.’ He mentioned how sad he was not to be ‘lolling on that Quincy St sofa … with my head in mother’s lap & my feet in Alice’s’. But by the end of the letter, to ward off any suggestion that he should come back at once to cure his homesickness, he cheerfully announced: ‘Cancel, dearest mother, all the maudlinity of the beginning of my letter; the fit is over; the ghost is laid … I assure you I shall do very well.’ From Geneva in the same year the 26-year-old tried it on again: ‘I feel my weekly palpitations at letter-time. I assure you dearest mother, they are violent. I am chronically, desperately, mournfully, shamelessly homesick.’

Henry James’s letters home can be read as sly and manipulative, but he wrote them for a good reason. He had been haphazardly educated by his parents to prepare him for nothing; they had kept him away from America for some of the crucial years of his adolescence, so his circle of friends, as these letters show, was extremely limited, many of his associates being also friends of the family. His parents had effectively banished their two younger sons, Wilkie and Bob, in whom they never had any great interest. They had made Alice, their only daughter, an invalid. And one evening in 1876 their father came home from an outing to announce that he had met the woman whom his son William would marry, whose name was also Alice. William duly married her. (Forty years later she became that same widow who disapproved of Edith Wharton.) In other words, the parents of Henry James had to be watched very carefully. Escaping them was an imperative. If illness, real or imaginary, kept them at bay, distracted them from doing damage, then it was a small price to pay. Had Henry James not managed them so carefully, he might never have got away. Or might never have managed the parting with such ease, such a lack of rancour, making clear to them once he had left for good that he loved them and missed them, and basking in the glow of their love and approval, but from afar.

Managing his family with slow doses of deceit was also useful to James as a novelist for whom secrecy and subterfuge was a great theme, the bedrock on which his best novels were built. Manipulating others, bending them with subtlety towards your will, sweetly deceiving them, was something his characters would do with considerable skill. Sometimes, as with Chad Newsome in The Ambassadors, it would be done with something approaching innocence; at other times, as with Madame Merle in The Portrait of a Lady or Kate Croy in The Wings of the Dove, it would be done out of dark need; in the end, as with Maggie Verver in The Golden Bowl, it would be done with aplomb and so stylishly that no one was sure they had noticed.

During this first visit alone to Europe, which began in February 1869 and ended in April 1870, James saw a great deal. Many of his visits to painters and writers were set up for him by Charles Eliot Norton, 16 years his senior, who had published his early essays in the North American Review and was one of the founders of the Nation. Norton and his family were also in Europe at the time of James’s visit. (Some of James’s most stilted and insufferable letters in these two volumes were written to members of the Norton family.) With the Nortons in London, James saw Leslie Stephen, whom James’s father had also known, and met Charles Dickens’s daughter, who was, he reported to Alice, ‘plain-faced, ladylike (in black silk & black lace)’, and visited William Morris and his family. Mrs Morris was ‘a figure cut out of a missal … It’s hard to say whether she’s a grand synthesis of all the pre-Raphaelite pictures ever made – or they a “keen analysis” of her – whether she’s an original or a copy. In either case she is a wonder.’ With Charles Eliot Norton he visited Ruskin’s house and saw his paintings, and later, went with the Nortons to see Charles Darwin (Charles Eliot Norton’s sister-in-law, Sara Sedgwick, would later marry Darwin’s son). ‘Darwin,’ he wrote to his father, ‘is the sweetest, simplest, gentlest old Englishman, you ever saw … He said nothing wonderful & was wonderful in no way but in not being so.’

Soon before he left England in May 1869, James went with Sara Sedgwick and Grace Norton to see George Eliot. His father, who received a description of her from Henry, had a right to feel that you could send the young lad anywhere and it would be money well spent:

To begin with she is magnificently ugly – deliciously hideous … Now in this vast ugliness resides the most powerful beauty which, in a very few minutes steals forth & charms the mind, so that you end as I ended, in falling in love with her. Yes behold me literally in love with this great horse-faced blue-stocking. I don’t know in what the charm lies, but it is thoroughly potent.

James then tried to list her characteristics: ‘a broad hint of a great underlying world of reserve, knowledge, pride & power – a great feminine dignity & character in these massively plain features – a hundred conflicting shades of consciousness & simpleness – shyness & frankness – graciousness & remote indifference – these are some of the more definite elements of her personality.’

After much prevarication in Switzerland, James finally made his way into Italy at the end of August 1869, noting ‘the delight of seeing the north slowly melt into the south’, unaware of what a momentous occasion this was, this small step over the border that summer, for the novels he would write. This sense of him wandering innocently and voraciously, not knowing how important some of these places would become both for him and his readers, makes these pages thrilling. It is hard not to shiver when he writes to his mother in November from Rome of his visit to

that divine little protestant Cemetery where Shelley & Keats lie buried – a place most lovely & solemn & exquisitely full of the traditional Roman quality – with the vast grey pyramid inserted into the sky on one side & the dark cold cypresses on the other & the light bursting out between them & the whole surrounding landscape swooning away for very picturesqueness.

Nine years later he would bury his character Daisy Miller in this graveyard, ‘in an angle of the wall of imperial Rome, beneath the cypresses and the thick spring-flowers’. By the end of the century he would often find himself standing in the cemetery at the grave of his friend Constance Fenimore Woolson, who committed suicide in Venice in 1894; her grave was close to those of the sculptor William Wetmore Story, about whom he would write a book, and John Addington Symonds, on whom he would base his story ‘The Author of “Beltraffio”’.

During this first visit to Italy he was stepping lightly on places he and his characters would subsequently grow to know intimately, to suffer in, to haunt. He studied churches and pictures and pieces of sculpture with enormous care. There is a constant impression in these months of his eye feasting on things, his sensibility sharpened and refined by travel and solitude; he is ready to make sweeping, confident, discriminating judgments for the benefit of the folks at home. Some of these letters, with their tone of pure youthful delight, have a greater urgency and fluency than the essays in Italian Hours. At the end of 1869, for example, he wrote to William about the Raphaels he had been seeing in Rome:

There was in him none but the very smallest Michael Angelesque elements – I fancy that I have found after much fumbling & worrying … the secret of his incontestable thinness & weakness. He was incapable of energy of statement … this energy – positiveness – call it what you will – is a simple fundamental primordial quality in the supremely superior genius … I felt this morning irresistibly how that M. Angelo’s greatness lay above all in the fact that he was this man of action – the greatest almost, considering the temptation he had to be otherwise – considering how his imagination embarrassed & charmed & bewildered him – the greatest perhaps, I say, that the race has produced.

James spent most of his time in Italy alone. It is possible that these months spent contemplating great monuments and looking at paintings in detail marked a crucial change in his ambitions. This tour was not merely about getting away from his family or tackling his so-called health problems; it also offered him a much grander and richer scenario than had come his way among his Boston associates. Michelangelo’s ‘high transcendent spirit’ rescued James from the limited universe of the Jameses, the Nortons and the Sedgwicks, the dull world of Boston letters. When, two years after his return from Europe, William and some of his friends in Boston founded a club, James wrote to Charles Eliot Norton: ‘My brother & various other long-headed youths have combined to form a metaphysical club, where they wrangle grimly & stick to the question. It gives me a headache merely to know of it.’ A few months earlier he had written to Norton about his friend William Dean Howells:

His talent grows constantly in fineness, but hardly, I think, in range of application. I remember your saying some time ago that in a couple of years when he had read Ste Beuve, he would come to his best. But the trouble is he never will read Ste Beuve, nor care to. He has little intellectual curiosity; so here he stands with his admirable organ of style, like a poor man holding a diamond & wondering how he can wear it. It’s rather sad, I think, to see Americans of the younger sort so unconscious and unambitious of the commission to do the best.

As James wrote these letters from his parents’ house in Boston, it was clear that he could not stay much longer in such a city, where ambition was limited and young intellectuals stuck to the question; within four years he would be gone for good.

James did not find his family interesting enough to use them much as models in his fiction; it is possible to find traces of Alice in The Bostonians and The Princess Casamassima, but of William there is hardly anything. William Dean Howells’s unworn diamond became useful when James needed an American character for The Ambassadors whose sensuous nature had been stifled by America to be woken – too late – by the glory of Paris. By the time he left America, James’s knowledge of its society was deeply limited and seriously etiolated. This lack of deep roots was an enormous help, a great gift, to him in his fiction; it forced him to concentrate on character and style and saved him from writing dull novels about changing social mores or failed dreams in American society.

He based his early Americans on himself and then when he needed a few more models he did not look far. His cousin Minny Temple gave him the basis for characters in a number of short stories, including Daisy Miller, and for Isabel Archer in The Portrait of a Lady and Milly Theale in The Wings of the Dove. Friends from Boston whom he befriended again in Italy, and who also appear in these letters, Francis Boott and his daughter, Lizzie, gave him Gilbert Osmond and his daughter, Pansy, for The Portrait of a Lady and Adam Verver and his daughter, Maggie, for The Golden Bowl. He needed only four Americans and himself to feed his rich imagination. And he needed a couple of ideas, the sort of ideas that William’s friends in his metaphysical club would not have much interest in. These came to him easily and simply; he formulated them, on the basis of his feelings and his observations, in a letter to William written from Malvern in 1870. He was attacking English women:

I revolt from their dreary deathly want of – what shall I call it? – Clover Hooper has it – intellectual grace – Minny Temple has it – moral spontaneity. They live wholly in the realm of the cut & dried … I find myself reflecting with peculiar complacency on American women. When I think of their frequent beauty & grace & elegance & alertness, their cleverness & self-assistance (if it be simply in the matter of toilet) & compare them with English girls, living up to their necks among comforts & influences & advantages which have no place with us, my bosom swells with affection & pride.

The name of his cousin Minny Temple, who was two years younger than James, appears regularly in these letters. In the summer of 1865, after the Civil War, she tried to find a room for James and Oliver Wendell Holmes Junior, who would become one of her admirers, where she was staying in North Conway, only to find that there was only one bed in the room they would have to share, which caused James to write to Holmes: ‘If you don’t mind it, I don’t as the woman said when the puppy dog licked her face.’

As James began to travel in Europe in 1869, Minny, who was slowly dying of tuberculosis, was still hoping to visit Italy; she had come close to asking him to take her there. But he was travelling alone. From Brescia in September 1869 he asked in a PS, ‘What of M. Temple’s coming to Italy?’ and he asked the same question again a week later from Venice. Once more the following February from Malvern he wrote: ‘A[unt] Kate mentions that Mrs Post [a cousin] has asked Minny to go abroad with her. Is it even so?’ And then later that month in a letter to Alice he said: ‘I have been very sorry to hear of Minny’s fresh hemorrhages – & feel glad to have lately written her a long letter.’ When his father wrote in March 1870 to tell him, still in Malvern, that Minny was very ill, he replied: ‘I was of course deeply interested in your news about poor Minny. It is a wondrous thing to think of the possible extinction of that immense little spirit … But something tells me that there is somehow too much of Minny to disappear for some time yet – more life than she has yet lived out.’

Minny died a few days later, while James was still at Malvern. When he heard the news he wrote two letters, one to his mother and one to William. These letters, which are in the Houghton Library, where many James family papers are housed, are among his most remarkable and ambiguous. Odd and confused in tone, they remain open to many interpretations. It is interesting that a note at the bottom of the first of them as it appears in these volumes states: ‘The original ms is now damaged. The bracketed, italicised insertions are taken from an examination of HJL 1’ – Leon Edel’s edition. ‘It is possible that Edel saw the undamaged manuscripts.’ A note at the end of the second uses a small variation: ‘It is possible that Edel worked from an undamaged manuscript.’

These two letters have become even more interesting because of the sharp and fascinating commentary on them by Lyndall Gordon in A Private Life of Henry James: Two Women and His Art (1998), which is the best single book about James. In the letter that broke the news, James’s mother expressed her regrets for ‘dear bright little Minny’. Gordon wrote about James’s reply: ‘James grovelled over this morsel of praise: “God bless you dear Mother, for the words. What a pregnant reference in future years.” This young man, who had savaged Dickens and Whitman, could contemplate his mother’s banality as a marvel of insight – a measure of her power over him at the age of 27.’ Gordon also considered those brief questions about Minny which James had asked in his letters from Brescia and Venice. ‘There was a wilful blindness in the way he would not grasp the gravity of her illness and the urgency of her pleas to him to take her on.’

After Minny’s death, Gordon wrote, James ‘tried to impress on his conscience the fact of loss, but what he actually felt was all gain … He told William: “While I sit spinning my sentences she is dead.” In some way her death and his act of writing were linked, as though her vitality had passed to him.’ Gordon is superbly interesting about James as an artist mourning his cousin in the short time after her death and then suddenly working out ways in which he would make use of her life in the future. In Gordon’s version of this story, which is carefully argued and not easy to summarise, James felt ‘enlarged’ by Minny’s death: ‘She was to fill, not empty, his life.’

James’s way of handling his mother, however, praising her banality ‘as a marvel of insight’, was not only a sign of her power over him, but of his over her. The tone he took with her was a necessary refusal to take her seriously, a way of keeping her at a distance. It is what many young men do with their mothers. Also, James at 27 had never before experienced the death of anyone he knew well. (‘I have been hearing all my life of the sense of loss wh. death leaves behind it: – now for the first time I have a chance to learn what it amounts to.’) While he could read several languages and make many fine distinctions, he was, from an emotional point of view, unusually inexperienced; this mixture of pure intelligence about books and places and real obtuseness about difficult emotions was, as it remains, quite a common condition for a young man of his type.

It should also be made clear that he was three thousand miles away, unable to express his responses to his cousin’s death in normal conversations over days with others who had known her. (‘I wish I were at home to hear & talk about her.’) Instead, he had to put his thoughts down on paper. No one should be surprised that his thoughts were confused and that his tone suggested, as he tried to let the fact of her death soak in, many contradictory feelings. James sought to console himself by the thought that some good might come of her death, that she might live fruitfully in the memory of those who had known her, or that she had been destined not to live and would not have been happy in full healthy adulthood.

Nonetheless, there is something odd in his telling his mother in the opening of his letter on the death of Minny that he had ‘been spending the morning letting the awakened swarm of old recollections and associations flow into my mind – almost enjoying the exquisite pain they provoke’. He moved in the letter from pure sorrow and regret to attempt to say more complicated things. Referring to the fact, for example, that Minny had no personal fortune and could not have thrived within the confines of the domestic sphere, he wrote: ‘No one who ever knew her can have failed to look at her future as a sadly insoluble problem – & we almost all had imagination enough to say, to ourselves at least, that life – poor narrow life – contained no place for her.’ He ended his letter: ‘My letter doesn’t read over-wise; but I have written off my unreason.’

It was clear in his letter to William, however, that he had a good deal more unreason to get out of his system. ‘A few short hours have amply sufficed to more than reconcile me to the event & to make it seem the most natural,’ he wrote,

the happiest, fact, almost in her whole career. So it seems, at least, on reflection: to the eye of feeling there is something immensely moving in the sudden & complete extinction of a vitality so exquisite & so apparently infinite as Minny’s. But what most occupies me, as it will have done all of you at home, is the thought of how her whole life seemed to tend & hasten, visibly, audibly, sensibly to this consummation. Her character may be almost literally said to have been without practical application to life. She seems a sort of experiment of nature – an attempt, a specimen or example – a mere subject without an object. She was at any rate the helpless victim & toy of her own intelligence – so that there is positive relief in thinking of her being removed from her own heroic treatment & placed in kinder hands.

It is hard at this point not to wish that someone from Porlock had arrived in Malvern to distract James as he wrote, or that someone at the Houghton Library had further damaged the manuscript of this letter before Edel got his hands on it. Because it gets worse:

Among the sad reflections that her death provokes, for me, there is none sadder than this view of the gradual change & reversal of our relations: I slowly crawling from weakness & inaction & suffering into strength & health & hope: she sinking out of brightness & youth into decline & death. It’s almost as if she had passed away – as far as I am concerned – from having served her purpose – that of standing well within the world, inciting & inviting me onward by all the bright intensity of her example.

James, like most artists, knew what he was doing only some of the time. He did not know at the time of Minny’s death that he would devote his life to the writing of fiction, although he might have guessed. He did not coldly and ruthlessly set out to use his cousin. His plans for his work were mostly tentative. Minny made her way into his fiction gradually and then forcefully, precisely because her life and her death haunted him in complex ways. He saw what he could make her become. ‘Greatness in a novelist,’ Gordon observed, ‘is a power to see people not only as they are but as they might be.’ In the creation of Isabel Archer, James freed Minny from death, from economic constraints – but most important, as Gordon points out, he freed her imagination.

Her memory, in turn, freed James’s imagination. It is a part of his mixture of deep self-absorption and steely and manipulative determination, much of which is evident in these letters, that he took what she gave him without any hesitation. In his travels, as in his childhood, he had learned something besides Boston decorum. In 1880, when the serialisation of The Portrait of a Lady began, he received a letter from Boston, from Grace Norton, saying that the story interested her but suggesting that James had based Isabel on his dead cousin. James, in his reply, stood his ground as a novelist in the most magisterial way, using a tone, managing ‘an energy of statement’, that might put Boston back in its place: ‘Poor Minny was essentially incomplete and I have attempted to make my young woman more rounded, more finished. In truth, everyone, in life, is incomplete, and it is [in] the work of art that in reproducing them one feels the desire to fill them out, to justify them, as it were. I am delighted I interest you; I think I shall to the end.’

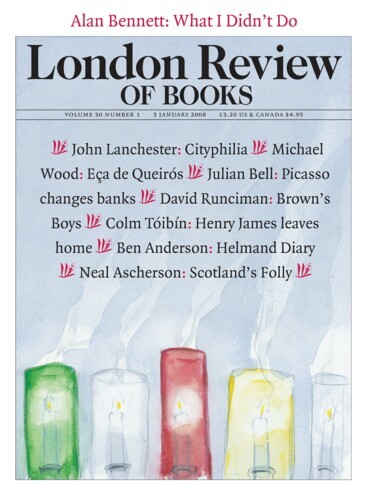

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.