Throughout the summer of 1763, a succession of Indian chiefs journeyed through the forest west of the British colonial town of Albany, New York, all heading for a single destination. Tuscaroras, Onondagas, Cayugas, Senecas and others: all of the Six Nations of the famed Iroquois Confederacy were represented. The focus of their attentions was a white man living in their midst, whose father had died the previous winter far away in Ireland.

They would arrive in groups at this man’s large and stately home, and would enact for him their ancient tribal ceremonies of ‘condolence’. They would adorn his face and body with long belts of wampum beads, and give him ritually purified water to drink, and chant doleful songs of mourning. ‘As you now sit in darkness,’ they would finally intone, ‘we remove all the heavy clouds that surround you, that you may again behold light and sunshine.’ Some months later, to fill the void left by parental death, they would offer him a young woman recently captured from an enemy tribe. The recipient of these demonstrations, for his own part, would know exactly how to respond – in their languages, and according to the traditional forms. Not a step would be missed on either side.

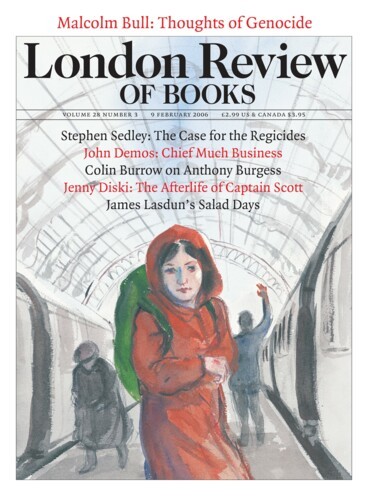

This elaborate scene, a virtual apotheosis of cultural boundary-crossing, opens Fintan O’Toole’s White Savage, on the fascinating career of William Johnson in 18th-century British America. Though well-known to scholars, Johnson’s story has not hitherto received the notice it deserves from the general readers who are clearly targeted here. O’Toole plans two follow-up volumes; his overall project is to unravel ‘America’s myth of itself, and the part played by one particular culture – that of Ireland – in its creation’.

William Johnson’s life began on a farm not far from Dublin in 1715. His father, Christopher, the man whose death a half-century later would be so fulsomely acknowledged in the American wilderness, was ‘head tenant’ for part of a large estate owned by a branch of his relatives, the Warrens. Through them, the Johnsons were linked to a cadre of prominent Catholic families, some of which had figured strongly in the doomed Irish rebellions of the preceding century. They lived now in a kind of Jacobite backwash, still prominent and still true to their past, but aspiring as well to accommodate themselves to the political and social realities of English rule. The sine qua non of such accommodation was conversion to Protestantism, a step taken by (among others) an uncle of William’s, Peter Warren. Warren would ultimately become admiral of the fleet and famous as a British naval hero; he would also serve as a model, and patron, for his nephew.

By marrying into a leading family of Dutch New Yorkers, the Delanceys, Warren acquired a direct stake in the American colonies, and began amassing vast amounts of property there, both on Manhattan Island and in the hinterland to the north. In the mid-1730s he proposed that his nephew ‘settle’ and develop a large portion of these holdings; the young man (now just past 20) fairly leapt at the chance. Soon William had converted to Protestantism, and left Ireland – for good, as it turned out – in order to begin a new career overseas.

Having reached the Warren lands alongside the Mohawk River, with a dozen Irish tenant families in tow, William bent to his task: clearing forest, planting hay, corn and other grains, raising herds of sheep and cattle. But he was also immediately drawn to the lure of trade with the native peoples living nearby. Thus began an almost meteoric rise in his fortunes. Textiles, ironware, guns and other products from overseas flowed in large quantities towards his warehouses along the Mohawk, there to be exchanged for animal skins provided by indigenous hunters. Within a scant few years he had joined the topmost tier of colonial ‘Indian traders’. This enabled him to cut loose from his uncle’s sponsorship; in short order, he obtained much more land, built himself a handsome house, and became fully his own man.

Johnson’s trade with the Indians ripened steadily into a deeper form of connection. He seemed to have an instinctive feel for their cultural ways, especially those of his closest neighbours, the Mohawks. He learned their language, their diplomatic protocols, their intricate ritual performances. He adopted their traditional dress (at least on some occasions) and joined in their political councils. They, in turn, reciprocated his interest and friendship; their partially Europeanised chief, Hendrick, became his special partner in all sorts of intercultural exchange. In due course they formally adopted him into their nation, and gave him a suitable Mohawk name, Warraghiyagey, meaning ‘a man who undertakes great things’, or, in a looser translation, ‘Chief Much Business’. Johnson’s New York contemporary and friend Cadwallader Colden would later comment that there was ‘something in his natural temper suited to the humour of the Indians’. As a result, ‘he made a greater figure and gained more influence’ among them ‘than any person before him’.

This influence came to be felt in the halls of power – from the province of New York, westwards to trans-Appalachia and northwards to French Canada, and from there across the ocean to the court in London. In fact, Johnson became an increasingly vital cog in the machinery of colonial governance. Time after time his estate provided the setting for large conferences with Indian leaders; treaties were made, and alliances formed, under his direct supervision. He was knighted for his services to the Crown, and made a baronet, and was later appointed ‘sole superintendent for Indian affairs’ in British North America; in addition, he served as a major general in charge of various military forces during the decade-long struggle known in the colonies as the French and Indian War (1754-63).

His wealth and social standing grew in parallel to his political importance. He eventually owned some 170,000 acres, a total matched by few, if any, of his colonial contemporaries. (Most of this, to be sure, was deep wilderness.) The last of his three successive residences, finished in 1763 and known as Johnson Hall, was an elegant Georgian structure, surrounded by satellite ‘lodges’ and other outbuildings; close by was the village of Johnstown, which he had founded for the benefit of his many tenants and retainers.

His personal life was no less extraordinary. He loved many women, and married none. His first clearly identified paramour was a runaway German servant-girl, who bore him three children during the 1740s. Then, towards the end of the same decade, he began his longest and most important relationship, with a Mohawk woman called Molly Brant, who would soon become his mistress in several senses: sharing his bed, hosting his tribal conferences, and presiding in matriarchal fashion over his ever-expanding household. With her, Johnson fathered and raised eight more children. He had still other lovers (French, Indian, English) more briefly encountered, and other offspring less fully acknowledged.

It was, above all, in his home that these various life-threads converged. There was elegant imported furniture, silverware and china to grace his table, paintings to hang on the walls, along with buffalo skins strewn on the floors, and a startling array of Indian artefacts. He received a steady stream of literary journals and books from England, and maintained a strong interest in applied science. He founded a school in Johnstown for both white and Indian pupils, and raised his own mixed-race children in the manner of European aristocrats. His retinue included a physician, an attorney, a farm manager, assorted clerks and scribes, a small band of house musicians (including a ‘dwarfish’ fiddler and a blind Irish harpist), Indian servants, African slaves, and a rotating line-up of (mostly Irish) cronies and gofers. He was also frequently visited by native chieftains with their councillors and families – sometimes on errands of trade or diplomacy, but often enough for the sake of sheer sociability.

The reputation of Johnson, and of ‘this wild place’ (as he sometimes called it), spanned half the world. A popular English novel of the period was based on his life. A London gentleman (and former New York governor) wrote to him of widespread speculation as to the number of ‘Indian concubines you had’; the same gossip ‘fixed upon you . . . as many children . . . as the late Emperor of Morocco . . . which I think was 700’. Friends and strangers alike came to view the scene for themselves, ‘from parts of America, from Europe, and from the West Indies’. One visitor left an especially detailed description of everyday life at Johnson Hall:

The gentlemen and ladies breakfasted in their respective rooms, and, at their option, had either tea, coffee or chocolate, or if an old, rugged veteran wanted a beef-steak, a mug of ale, a glass of brandy, or some grog, he called for it, and it always was at his service. The freer people made, the more happy was Sir William. After breakfast, while Sir William was about his business, his guests entertained themselves as they pleased. Some rode out, some went out with guns, some with fishing-tackle, some sauntered about the town, some played cards, some backgammon, some billiards, some pennies and some even at nine pins. Thus was each day spent until the hour of four, when the bell punctually rang for dinner, and all assembled.

He had besides his own family, seldom less than ten, sometimes thirty. All were welcome. All sat down together. All was good cheer, mirth and festivity. Sometimes seven, eight or ten of the Indian sachems joined the festive board. His dinners were plentiful. They consisted, however, of the produce of his estate, or what was procured from the woods and rivers, such as venison, bear and fish of every kind, with wild turkeys, partridges, grouse and quails in abundance. No jellies, creams, ragouts or sillibubs graced his table. His liquors were Madeira, ale, strong beer, cider and punch. Each guest chose what he liked, and drank as he pleased. The company, or at least a part of them, seldom broke up before three in the morning. Everyone, however, Sir William included, retired when he pleased. There was no restraint.

The key sentence here is the last one. Johnson’s mystique – the word does not seem too strong – was rooted in his apparent freedom from the scruples and conventions that framed the lives of other Britons. He made his own rules, and pursued his own interests, exactly as he pleased. There was indeed ‘no restraint’ on him.

All this and more appears in the pages of White Savage. The story is intrinsically and indubitably compelling. But how does it fare as popular history? And what is popular history anyway? Perhaps this book can serve as an instructive case-in-point.

First and foremost is the centrality of specific events. Popular history, here and elsewhere, unfolds as a sequence of happenings: of decisions made, steps taken, successes achieved, sufferings endured, results attained. At times this progression can be lively and informative; event-driven history has at least the advantage of motion. Yet it can also be mind-numbing, as in the lengthy middle chapters of White Savage, where Johnson’s political, military and diplomatic activities are minutely detailed, one after another after another.

Ideas and interpretations, meanwhile, receive short shrift. And when they do appear, their presence seems forced, their positioning incongruous. In White Savage, Johnson’s Irishness drops heavily in and out of view, used to explain things as disparate as his sympathetic attitude towards Indian spirituality, his gifts as a negotiator, his comfort with cultural borderlands, his ability to ‘broadcast simultaneously on many channels’ (this in contrast to the ‘monophonic . . . voice’ of a ‘straightforward Englishman’), and the ‘unrestrained’ atmosphere he created at Johnson Hall. Irish this, Irish that, Irish the other: it becomes tiresome and, finally, implausible. By the same token – but on the opposite (Indian) side – a careful depiction of ground-level trading practices suddenly explodes into a bald characterisation of Iroquoia as a ‘consumer society’, featuring ‘increased individualism’ (thanks to the introduction of European firearms), a ‘new sense of self’ (thanks to European mirrors), and a rise in ‘male vanity’ (thanks to imported cosmetics). Such claims are asserted rather than demonstrated; to a reader they feel like interpretive missiles launched without plan or preparation from some authorial place-on-high.

Other elements of popular history, also evident here, can be more briefly mentioned. For the most part, character and personality trump situation and circumstance. Johnson above all, but also Hendrick, Molly Brant, General Jeffrey Amherst, and a host of lesser figures in a large cast seem to push things ahead by force of their own will and explicit purposes. By contrast, little is said about the wider political and imperial framework within which all these individuals – especially Johnson himself – were obliged to operate, and even less about such obviously important contextual factors as the prevalent economic culture and the natural environment. Put differently: the story as presented here makes its various characters stand free of their appropriate, and necessary, surroundings.

Yet the work proceeds in an entirely confident, declarative, almost declamatory mode. There is no room for questions or debate, and thus little engagement with (or even acknowledgment of) other scholarship. The footnotes suggest at least a degree of acquaintance with previous Johnson-related writings, but none of this enters the text. Moreover, White Savage is – again, like most popular history – openly partisan. Johnson himself appears consistently heroic, and Hendrick has the status of a ‘great sachem’. British generals, however, come off poorly; Amherst is portrayed as narrow-minded, and given to ‘genocidal fantasies’, while his colleague James Abercromby displays nothing less (or more) than sheer ‘idiocy’. Such undisguised preferences add a certain bite to the story, but they also close off the chance for independent judgment.

Popular history requires a snappy prose style. Writerly effects are to be expected; and here White Savage does not entirely disappoint. From time to time it offers phrases and sentences of real power: naming Lake George, in eastern New York, ‘after the British monarch turned this thin, sharp stretch of clear water into a symbolic dagger thrust towards the enemy’ – the enemy is Canada. Yet for every clever bit, there is another that falls flat. Consider the book’s very first line: ‘One thing leads to another. Causes have their effects.’ Well, yes.

A final characteristic of popular history is a predilection for past-to-present connections; in this regard, White Savage goes way over the top. Its subtitle, ‘William Johnson and the Invention of America’, can be considered an early warning. Hints of such ‘invention’ are scattered through the intermediate sections; then, in a concluding chapter entitled ‘The Afterlife’, the matter is fully laid out. Here we confront Johnson’s supposed ‘legacy’ to American culture at large (and ever since). As glimpsed through the writings of two (only two) 19th-century novelists, Johnson becomes ‘the archetypal republican hero’, an exemplar of ‘a specifically American style of manly virtue’, the embodiment of ‘a new political order’, a ‘harbinger of . . . democratic revolutions to come’ and even, finally, ‘the American superman’.

Enough. This is the same Johnson who so fascinated his contemporaries because of his singularity (as opposed to his ‘archetypal’ significance), who considered himself an especially loyal British subject, who would be remembered by succeeding generations as an opponent of the movement for an independent America. His death in 1774 foreclosed what would probably have been a central role with Crown forces fighting to suppress the revolution. Moreover, Molly Brant, who outlived him, together with his various children, warmly embraced ‘loyalism’, and fled to Canada when that cause was lost. His legacy, as Molly and others would later preserve it, was more Tory than ‘democratic’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.