You know you’re getting old when sleeping with a vampire no longer gives you a sickly thrill. At the age of ten or eleven, having absorbed the requisite number of creaky old Bela Lugosi films, I evolved such a baleful Dracula-fear that I began sleeping every night with one arm slung backwards over my neck. This neurotic and slightly awkward posture – still habitual, I’m embarrassed to say – was meant to be prophylactic: even while snoozing, I figured, I’d be ready to fend off any emissaries from the undead who tried to bite me.

Now I wonder, though, if it wasn’t also a bit of perverse provocation, part of the prepubescent come-hither act. The great thing about vampires, after all, was that they really cared about you. They were interested in you personally! So much so in fact that they would rise up out of their coffins, wamble over long distances (all the way from Transylvania) and sneak into your very own bedroom just to suck the blood out of you. It was weird but peculiarly gratifying.

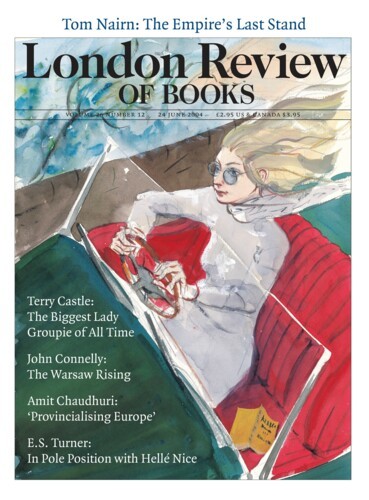

Reading about Mercedes de Acosta, poet, playwright, memoirist, Hollywood screenwriter and lesbian seductress extraordinaire, brings it all back. By all accounts, de Acosta (1893-1968) was a serious lady ghoul. So lamia-like her sartorial mode – she favoured black silk cloaks and trousers, tricorn hats, blood-red lipstick and cadaverish white face-powder – Tallulah Bankhead was not the only acquaintance to nickname her ‘Countess Dracula’.

Yet such was de Acosta’s sinister allure she managed to bed just about everybody who was anybody in the sapphic world of her time: from Isadora Duncan, Alla Nazimova, Pola Negri, Tamara Karsavina, Katharine Cornell, Marie Laurencin, Michael Strange and Eva Le Gallienne in the 1920s and 1930s to Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Hope Williams, Libby Holman, Ona Munson (Belle Watling in Gone with the Wind), Poppy Kirk (a Schiaparelli model and prominent diplomat’s wife) and many others in Hollywood, Paris and New York in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. She had ‘a small white body, like a small marble park’, an infatuated Janet Flanner wrote, ‘in which her eyes lived as brown nightingales’. Her hair was a ‘lignous’ coiled black, like a ‘combed bush’. De Acosta boasted that she could steal any woman from any man.

Garbo, who allowed herself to be briefly seduced then struggled for twenty years to extricate herself from de Acosta’s succubus clutches, called her ‘Miss Black and White’; a cynical yet mesmerised Alice B. Toklas admired her ‘dear Mercedes’s’ indestructible chic. According to Truman Capote, de Acosta was by far the best card to hold in the café society game known as International Daisy Chain, the goal of which was to ‘link people sexually, using as few beds as possible’. (With one lucky stroke you could ‘get to anyone from Cardinal Spellman to the Duchess of Windsor’.) And even in her troubled later years – she took to wearing a Wotan-like eyepatch in the 1950s, after pouring cleaning fluid into her eye instead of eyewash – she retained her dark charms. Living a hand-to-mouth existence in New York after the failure of various literary projects in the early 1960s, she nonetheless continued picking up nubile girls with aplomb, including (says Robert Schanke) a ‘tubercular young British actress who was a waitress in a coffee shop’.

Once one might have welcomed such a seduction, fang marks, TB and all. I remember much relishing de Acosta’s gossipy 1960 autobiography, Here Lies the Heart, when it was reissued by an American gay press in the 1970s. (The deeply closeted Eva Le Gallienne, appalled by de Acosta’s lack of discretion, said it should have been called ‘Here the Heart Lies and Lies and Lies’.) The book was for some years an underground lesbian classic, not least on account of de Acosta’s breathless description, complete with deliciously amateur Brownie snapshots, of a clandestine love-tryst she had with Garbo in 1931 at a summer cabin in the Sierras owned by the film actor Wallace Beery. In one brazen snap, the epicene GG poses topless in sneakers and tennis shorts, a sweater around her neck and an adorable little white beret perched stylishly on her head. She’s brown, louche and Amazonian, and more distressingly beautiful than in any official studio publicity shot I have ever seen. O, for such beings to play ping-pong with! When the book came out, Garbo never forgave de Acosta for what she considered the extraordinary, sottish violation of her privacy.

But after reading the new biography and a few of de Acosta’s quite staggeringly awful plays one is tempted to demur. Seductive she may have been – Pola Negri? Isadora? Garbo and Dietrich? – but also dumb, spoiled, a headcase, and in the end oddly tedious. Once she got past one’s defences, Cuban heels a-clicking, she seems rapidly to have palled. I guess that’s the problem with erotomaniacs (and Schanke is convinced she was one): they wear out their welcome in a hurry. (If you’re middle-aged and female, by the way, you definitely need to worry about this disorder: like that of adult diabetes, the ‘average age of onset’, Schanke grimly warns the reader, ‘has been found to be between 40 and 55’.) ‘She’s done me such harm,’ Garbo complained to Cecil Beaton, ‘has gossiped so and been so vulgar. She is always trying to scheme and find out things and you can’t shut her up.’

Despite the Lugosian looks, Garbo concluded, de Acosta was ‘hopelessly feminine’, someone who needed ‘to possess and envelop one – with marriage or the equivalent’. A vampire, in other words, with a girlish hankering to settle down. She revealed as much in 1935, when, desperate to please her increasingly skittish inamorata (the ‘Swedish servant girl with a face touched by God’), she purchased an estate for herself and Garbo in Beverly Hills – it had a croquet lawn, a ten-foot-high privacy fence and separate entrances. In this fantasy retreat, which Garbo rejected peremptorily as soon as the work was done, saying she vanted a tennis court instead of a stoopid old cwoquet lawn, one sees de Acosta’s pathology writ large. What she really longed for was a sweet little vault somewhere, an apron to tie on over her Dracula cape, and a hellish little oven in which to bake blood-soaked pies for her lady love.

Schanke’s biography does little to dispel the banality of it all. Indeed, in a peculiar kind of coup, he manages to make de Acosta sound even more tiresome and foolish than she was. Even now, like a rhetorical Wonderbra, Here Lies the Heart has its moments of uncanny uplift – as, for example, when de Acosta describes her disquieting ‘moaning sickness’, an odd lifelong tendency to jolt awake every morning at 5 a.m. in a state of ‘painful bewilderment’, like someone just returning ‘from a long and fatiguing journey’:

Everyone has fallen asleep and awoken with a jerk. Eastern teaching tells us that this indicates a too sudden parting of the astral from the physical body. In my own experience, I believe I have gone out so far on the astral plane that it has been hard for me to find my way back, so that when I woke up I was dazed and felt lost. I believe this is an explanation of much of my moaning sickness and morning depressions, which in turn have caused my migraine headaches.

Schanke makes little of such charming lunacy. Despite dedicated sifting in a newly opened hoard of de Acosta manuscripts and theatrical memorabilia in the Rosenbach Museum in Philadelphia, all he really succeeds in evoking – in painfully gravity-bound prose – is the strange nullity of her existence. De Acosta was someone who lived her entire life through other people: you don’t get to be ‘the dyke at the top of the stairs’ (as Garbo’s friends called her) otherwise. But her relentless, obtuse, often clammy devotion to the famous women she pursued, the elusive Greta above all, makes for dispiriting reading. Surely vampires can’t be this dull and inane? What’s the point then of trying to get to know one?

By any superficial measure one might have expected more. De Acosta’s background was Iberian and exotic; she claimed to be descended from the fabled dukes and duchesses of Alba. Her father, Ricardo, was a wealthy steamship company executive who fled his native Cuba for New York under mysterious circumstances in the 1850s. De Acosta liked to maintain he was a heroic supporter of Cuban independence who had escaped a government firing squad – literally – by diving off the ramparts of Morro Castle into shark-infested Havana Bay, where he was picked up by an American schooner. It seems more likely, however, that he was a political snitch working on behalf of American and Cuban business interests and had to be hustled out of the country for his own safety. De Acosta’s mother, the romantic Micaela, an orphaned Spanish heiress living in New York, married him when she was 16. The couple subsequently had eight children, of whom Mercedes was the last. Despite her parents’ fanatical Roman Catholicism, the young de Acosta grew up a pampered member of New York high society. The family owned a lavish house on 47th Street, with Vanderbilts, Harrimans and Roosevelts for neighbours; her mother’s live-in cavaliere servante – and de Acosta’s godfather – was Ezequiel Rojas, the former president of Venezuela.

The pattern of de Acosta’s life – of her sentimental disorder – was established early. As various grisly poems unearthed by Schanke attest, her adolescent attachment to her mother was both pious and grandiose:

Pure as a lily, as white as snow,

Spreading sunshine, where e’re she may go,

Spotless beautiful, and sweet,

Giving her wisdom to whom she may meet.Lovely as the morning sun;

Bewitching as the evening sky,

Always striving, working to conquer,

At least to try.

Alas, poor Mercedes: she couldn’t have foreseen how the metrical dying fall in the last line would a century later ineluctably evoke the Monty Python song about the highwayman ‘Dennis Moore, galloping o’er the moor’:

Dennis Moore,

Dennis Moore,

Mr Moore.

None of Micaela’s odd childraising methods, which included dressing Mercedes up as a boy, telling her her real name was ‘Rafael’, and later, when her daughter got stroppy and confused, sequestering her in a convent boarding-school where she was forced to carry love notes back and forth between various mutually besotted nuns, could shake de Acosta’s affection. About her father she was less enthusiastic: she remained unmoved when he abruptly jumped into a gorge – with fatal results – at J.P. Morgan’s deluxe holiday camp for plutocrats in the Adirondacks in 1907. ‘He did not interest me as a person,’ she wrote later in her autobiography.

Yet most important of all to de Acosta was her flamboyant older sister Rita. Rita Lydig – her second husband was a wealthy New York businessman, Philip Lydig – was like one of Edith Wharton’s spoiled anti-heroines: sexy, insane, theatrical, improvident and entrancingly beautiful. She appears – a wanton in Worth gowns – in countless memoirs of Old New York. Men held her in near-cultic regard. Sargent and Boldini painted her; Rodin sculpted her. Puccini was supposed to have left his seat at the New York premiere of The Girl of the Golden West to sit behind her in her box, transfixed by the sight of ‘her provocative back’. (She is said to have worn the first backless evening dresses in modern fashion history.) A butch little sister – Mercedes was 18 years younger and seems to have played the role of tomboy mascot to Rita’s rackety grande dame – might only marvel and gawp.

In the romance department, Wharton’s Undine Spragg had nothing indeed on Rita. Mrs Lydig went through lovers with the same abandon she displayed during month-long shopping sprees in Paris, London and New York. (At her death in 1929, she had 150 pairs of shoes, 75 Spanish fans, an 11th-century lace petticoat that had cost her $9000 and a houseful of Renaissance paintings, including Botticelli’s Venus. The last-mentioned inspired one of de Acosta’s first plays, about an imaginary love affair between the painter and his model.) Though Rita’s last years were troubled – her health was frail and she went broke in 1927 when Callot Soeurs sued her for non-payment of bills – she never lost her talismanic (and one suspects eroticised) place in her sister’s imagination.

Tellingly, especially given what would become a lifelong interest in spiritualism, de Acosta’s devotion to Rita seems at times to have verged on the paranormal. In Here Lies the Heart she describes a freak injury her sister suffered during one of her many surgeries:

When she was about to be wheeled into the operating room, I had a remarkable presentiment. I did not know then, and I do not know now, whether it is customary to put patients on an electric pad during an operation. I only know that, just in that second, I saw in my inner eye Rita burned on an electric pad.

I rushed after the nurses as they wheeled her down the hall and cried out: ‘Don’t put my sister on an electric pad!’ Rita heard the fear in my voice. She put her hand out to mine from under the blanket and said: ‘Don’t worry so, darling. Everything will be all right!’ I persisted and cried out again: ‘Don’t put her on an electric pad!’ A nurse half-nodded to me as one would to a tiresome child, and the doors of the operating room closed. I stood alone in the hallway. A cold sweat broke out all over me and I began to cry.

(Uh-oh, spaghetti-o’ . . .)

I waited so long that I knew something had gone wrong. I walked up and down that room and wrung my hands. I fell on my knees and prayed. Suddenly a nurse came in looking very disturbed. She said: ‘There has been an unfortunate accident. They put Mrs Lydig on an electric pad during the operation. It short-circuited and deeply burned the base of her spine. I am afraid it is a very bad burn.’

(Eeeek! I TOLD you not to put her on an electric pad!)

Although the burn led to serious complications – her ‘beautiful back’ was scarred for life – the lovely Rita never sued for damages. ‘She was too generous to do this,’ de Acosta writes: ‘she did not wish to hurt the surgeon’s reputation.’ (Water-cooler close-up of gorgeous, suffering Rita in hospital bed, forgiving sheepish-looking doctor.)

Somehow, with the scenery-chewing Rita in the picture, it’s no surprise that de Acosta became the biggest lady groupie of all time. Mercedes was a born sidekick: the loyal Gal Pal (with a dykey twist) whose most gratifying career moment comes when she is nominated for Best Supporting Actress in some tasteful, soon-to-be-forgotten ‘woman’s film’. In dedicating herself fairly squalidly to various Great Ladies of Stage and Screen she found a familiar (and comfortable) subjection. With every gasp of exaltation, each giant bouquet sent sailing over the heads of the orchestra, every slavish vigil at the stage door, she re-enacted – compulsively, one feels – the ecstasy and pathos of life with Big Sis.

De Acosta didn’t have to work her way up the celebrity ladder. Thanks to Rita’s friends and connections, who included the society decorator Elsie de Wolfe and her lover, the Broadway producer Elisabeth (Bessie) Marbury, she started right at the top, with the bisexual Russian-Jewish actress Alla Nazimova and then Isadora Duncan. The liaison with Nazimova – celebrated Ibsen actress and so-called ‘First Lady of the Silent Screen’ who was later to star (at a winsome 42) in the notorious 1922 all-gay Natacha Rambova film of Wilde’s Salome – began in 1916, when de Acosta saw her in the popular one-act melodrama War Brides. (She had already been intrigued by Nazimova’s gymnastic just-off-the-steppes act at a patriotic Madison Square Garden benefit on behalf of the Russian war effort. ‘As the band struck up the Imperial Anthem, Nazimova waved the Russian flag as a great spotlight played over her. Then the music changed to a wild Cossack strain and . . . she ran . . . around the arena, leaping into the air every few steps.’) Their fling was brief but Nazimova supported de Acosta’s novice playwriting efforts and remained a lifelong friend. Later, in Los Angeles, when both had become hardy perennials on the Hollywood lesbian circuit, Nazimova would try (to no avail) to wean de Acosta off her Garbo-fixation by dangling one of her own many ex-lovers, the unfortunate Ona Munson, in Mercedes’s direction.

De Acosta met Duncan in 1917 when Duncan was living on Long Island. The account of their relationship in Here Lies the Heart is full of Mercedes’s usual self-serving B-movie twaddle. (‘When I saw Isadora Duncan for the first time in my life she waved a scarf at me, and the last time I saw her she waved a scarf at me. And it was a scarf that killed her!’) On one unforgettable occasion, de Acosta wrote, Duncan danced for her privately for hours, barefoot and bacchante-like in ‘her customary Greek costume’:

I don’t know how long she danced but she ended with a great gesture of Resurrection, with her arms extended high and her head thrown back. She seemed possessed by the dance and utterly carried away. When she finished she dropped her arms to her sides and stood silently . . . . In that pause I think we both lived many lives. Then Isadora seemed to return from a far land and again she became conscious of me. I moved toward her and in a mutual gesture we flung our arms around one another, and stood there clinging to each other in silence and tears.

The reality was perhaps less sublime: the Indian dancer Ram Gopal, a friend of de Acosta’s in her later years, remembered her boasting that ‘Isadora liked to kiss my breasts and lick the moisture between my legs.’ Je me lance vers la gloire indeed.

The infatuation with the actress Eva Le Gallienne – her most important lover before Garbo – began in 1920, three days before de Acosta’s marriage to the New York society painter Abram Poole. As is often the case, marriage proved no impediment to sapphic love: the wealthy Poole both tolerated de Acosta’s female attachments and generously, if mysteriously, supported her until his death. (They lived most of their married life apart.) Le Gallienne, who was British, was then having her first runaway Broadway success, the lead role in Ferenc Molnár’s Ibsenesque drama Liliom, and was ambitious to extend her fame further. Though de Acosta at that point had had only one play produced – a feeble little farce entitled What Next! – Le Gallienne persuaded herself that she had found the ideal artistic collaborator. De Acosta’s conspicuous lack of talent was no deterrent: Mercedes would write the plays, Eva would star in them.

To judge by the works reprinted by Schanke in the companion volume to his biography, Le Gallienne has a lot to answer for. Sandro Botticelli is bad enough: an orotund costume drama in which Le Gallienne played the part of Simonetta Vespuccia, a Florentine courtesan with whom the painter falls tragically in love. It flopped miserably when it was produced in New York in 1923 and it is easy to see why. In the era of Shaw, O’Neill and Strindberg, de Acosta still worked almost entirely – as if obliviously – in the obsolete vein of 19th-century melodrama. In the opening scene, when various foppish courtiers gossip about Simonetta – she is supposed to be the mistress of Giuliano de Medici – one of them intones in a furtive stage whisper that ‘a beauty like hers seems almost a dangerous thing.’ ‘Yes,’ another rejoins, ‘it is like the beauty of an exquisitely sharp knife. The hilt may be jewelled, but if one comes too close, the blade draws blood!’ Delicious perhaps – the sort of thing one might say about a favoured old flame – but also pure Scarlet Pimpernel.

Other joint dramatic ventures fared equally badly. Jehanne d’Arc was staged in Paris in 1925, with Le Gallienne again in the lead role, a set design by Norman Bel Geddes, and luminaries such as Arthur Rubenstein, Cole Porter, Ivor Novello, Dorothy Parker and Mrs Vincent Astor in attendance on opening night. It closed after a few snaggle-toothed performances. In Jacob Slovak (1923), the one de Acosta play to have some success (John Gielgud appeared in a short-lived London production), Mercedes again depicted doomed heterosexual love. The heroine is a New England village girl who has a clandestine affair with her shopkeeper father’s Jewish assistant. (The drama was meant to be an indictment of anti-semitism.) It’s tempting, again, to recite some of the lines aloud, as when the love-struck Myra tells a startled Jacob how much she wants him:

I told yer I couldn’t help comin’ here – it’s like that, I couldn’t help this neither. Yer see with a woman it’s different – she’s got ter keep things all in here (she touches her brow), tormentin’ and tormentin’ her. I tried ter explain ter yer – I’ll try now. It started long ago. I used ter lay in bed night after night and think about this – my body hot. The branches of the trees knockin’ against the winder – I’d think it’s a man – a man knockin’ there – tryin’ ter get in. It never was a special man. I’d try ter put a face on his body, but no face I knew was right. I’d see him climbin’ through the winder and comin’ toward me – I’d throw the covers off – and, and clutch my pillow and cry. And then yer came, and my man’s body got a face – yer face. It got yer face because I loved yer – from the very first time I saw yer . . . So somehow I jest had ter have yer – ter make it true. Yer real body against mine. I had ter. I had ter.

It’s hard ter be readin’ and reviewin’ such stuff: I guess I jest had ter.

Finally, the lachrymose Mother of Christ, possibly the worst play ever written, was never staged at all, despite having had a reading by Eleonora Duse, who agreed to play the main part. (Luckily the Duse dropped dead before things got very far.) Blasphemously enough, the play depicts the Virgin Mary, ‘mother of the whole suffering world’, neurotically offering herself to Pontius Pilate as a substitute for her son, who is to be crucified the next day. In the climactic scene she visits Jesus in his dungeon and tries to guilt-trip him, in stereotypical Jewish mother-style, into letting her take his place. (‘You are the only thing I have in the world; the only one I love – yet you are the only person I do not understand, the only one who wounds me.’) After the crucifixion, as the curtain falls, Mary sits by the sepulchre praying that people will someday embrace her son’s message of ‘compassion, tolerance, understanding and forgiveness’. Schanke, generous to a fault, sees the scene as wistfully autobiographical. ‘As a woman who was living a complicated life with both a husband and a female lover, Mercedes was undoubtedly expressing her own dreams.’ My dumb husband and bossy girlfriend: what a cross I have to bear!

The gush seems to have been what doomed her in the end with Garbo. After breaking up with Le Gallienne, de Acosta moved to Los Angeles, eager to make money as a screenwriter in Hollywood. (She didn’t.) She met Garbo in 1931 through the writer Salka Viertel. She was struck at once by the actress’s ‘classical’ legs (‘not the typical Follies girl legs or the American man’s dreams of what a woman’s legs should be . . . They have the shape that can be seen in many Greek statues’) and supernatural likeness to her sister Rita. By the time of the tryst at Wallace Beery’s cabin, the excitable Mercedes had given herself over, body and soul, to her new love. Garbo, as she wrote in Here Lies the Heart, was like ‘some radiant, elemental, glorious god and goddess melted into one’.

But the torture began soon enough. Garbo, increasingly strange and wilful, made no bones about sleeping with anybody she fancied, including a series of comically improbable men. The more one reads about her the more one is forced to conclude she had one of the most jaded sexual personalities ever. Mercedes had to bite her lip and look away while her new paramour carried on, fairly cynically, with Leopold Stokowski, Cecil Beaton, the director Rouben Mamoulian, and George Schlee, the husband of her dress designer. De Acosta was reduced to trundling around the world in Garbo’s wake, waiting for the phone to ring. Every now and then Garbo would send her – without explanation – moronic cartoons clipped out of the newspaper.

Once de Acosta fell for Garbo her life was essentially over. True, she would live on for thirty more years, canoodling around and putting a semi-brave face on things. The rebound fling with Dietrich in 1932 must have been a tonic, especially if it is true, as one biographer believes, that Garbo and Dietrich had themselves had an affair long ago in Berlin and loathed one another with especial spite. (Some of Dietrich’s choicer comments on Garbo, preserved in a letter she wrote to her husband after meeting de Acosta, have the hard-edged Hausfrau bitchiness one associates with having been around the block a few times with someone: ‘I saw Mercedes de Acosta again. Apparently Garbo gives her a hard time, not just by playing around – which by the way is why she is in the hospital with gonorrhoea.’) Dietrich apparently comforted de Acosta in the requisite manner: in the Dietrich box in the Rosenbach archive Schanke found several scarves imprinted with the name ‘Marlene’, one of Dietrich’s yellow ankle socks, ‘bearing a lipstick smudge at the edge of the heel’, and a ‘single seamless stocking’. But after a few months, it seems, not even the obliging Blonde Venus could bear any more of the endless ‘droning on about Garbo’.

As de Acosta’s life began spiralling downward in the later 1930s and 1940s, she became increasingly nutty, fretful and gullible. Her screenwriting career having stalled out (she would complain bitterly to the end of her life that Salka Viertel had stolen her idea for a film on Queen Christina of Sweden in which Garbo would star), she supported herself during and after the Second World War as a magazine writer and editor. In between love affairs, often with younger women, she searched for spiritual solace. She lived for a brief period in an Italian convent, the acolyte of a certain Sorella Maria, then turned to theosophy and the mystic East. She met the Hindu guru Sri Meher Baba at a Hollywood party in 1934 and, impressed by his message of cosmic detachment, agreed to collaborate with him on a film of his life. He quickly disappointed her, however, by showing an unswamilike interest in the success of their movie. ‘Thinking and working on MY story would be BEST if you would just try to persevere,’ he wrote to her – no doubt annoyingly – when he thought she was wasting time and brooding too much over Garbo.

In desperation she switched her allegiance to Sri Ramana Maharshi, a rival yogic practitioner whose Truth Revealed (1935) had become a Beverly Hills bestseller. He played the holy man role more convincingly. In 1938 she made a pilgrimage to his ashram in Ceylon, where she found him, surrounded by tame monkeys, meditating in a darkened hut and naked ‘except for a loincloth’. She sat with him in silence for three days and immediately felt the veil of Garbo-maya lifting: ‘He moved his head and looked directly down at me, his eyes looking into mine,’ she wrote in Here Lies the Heart. ‘I felt my inner being raised to a new level – as if, suddenly, my state of consciousness was lifted to a much higher degree. Perhaps in this split second I was no longer my human self but the Self.’

Alas, though, such transcendence was fleeting. Once back in the United States, de Acosta reverted to her bad old human-self ways. Her last years were dismaying. Writing projects foundered; friends and lovers died (Ona Munson committed suicide in 1955); de Acosta herself had a physical and mental breakdown. Her income drastically reduced: when her ex-husband died in 1961 his executors at once cut off her allowance; she was forced to sell her papers to the Rosenbach museum to stay solvent. She had a brief return to the limelight in 1960 with the publication of Here Lies the Heart (‘Greta Garbo’s Pal Has Much to Tell,’ read one review) but the book also put paid – for good – to her troubled relationship with the eccentric screen star. When they met by accident in a health food store in New York in the early 1960s, Garbo stalked away without speaking. In an attempt to revive their aborted passion, de Acosta sent her a little blue spruce Christmas tree and a gift basket ‘full of toys, mistletoe and vodka’. Garbo kept the tree and the vodka but sent the toys and mistletoe back without comment. When de Acosta died in May 1968 – an event passing mostly unremarked in that otherwise busy month – neither Eva Le Gallienne nor Garbo attended her funeral.

What to make of it all? Schanke, unsurprisingly, is unable to find much dignity in de Acosta’s story. His attempts at pathos don’t help matters greatly. ‘With her beloved in Sweden,’ he writes at one point, ‘Mercedes walked alone the deserted roads they had walked together. Her hands ached for her lover, and her lips scorched [sic] from repeating her name.’ Despite the access to new archival material (the lipstick-smudged yellow sock, for instance), he brings little to the de Acosta/Garbo/Dietrich saga that hasn’t been treated better elsewhere – in Hugo Vickers’s Loving Garbo (1994) and Diana Souhami’s Greta and Cecil (1999). The attempt to rehabilitate de Acosta as a lesbian rebel and ‘role model’ – ahead of her time in her supposedly guilt-free embrace of same-sex desire – is unconvincing. The epithet in the book’s title is from Cecil Beaton’s diaries: after attending a Broadway premiere with a tricorn-hatted de Acosta in 1930, Beaton worried that people would gossip about seeing him with ‘that furious lesbian’. Unfortunately, That Furious Lesbian sounds more like an obscure 1970s American television sitcom than the name of a serious life study. Schanke regrets that de Acosta did not live to see the rise of ‘the new Gay Liberation Front, chanting "out of the closets and into the streets”’ – as if that would have mitigated any of the sludginess.

For the truth is, de Acosta wasted her life and was too dumb to understand how it happened. It’s not so hard, after all. For many years I have admired J.H. Plumb’s brazen three-word dismissal of George IV (in The First Four Georges) as ‘a worthless dandy’. Such judgment, however arguable, is thrilling in its moral confidence. And in the case of de Acosta one wants to be similarly free and cruel. She had money, looks, privilege, ambition and undoubted sexual allure. Late in life, at least according to one biographer, Garbo is supposed to have said of her that she possessed ‘a great knowledge of love. She excited me in everything she did.’ It’s hard not to enjoy – in the pimply, nocturnal, deeply credulous way that one does – such fantastical anecdotes as that related by Antoni Gronowicz in Garbo: Her Story (1990):

One evening in their hotel room, Garbo wept as she related to Mercedes how the late director Mauritz Stiller ‘had been in absolute control of her life’ and how his memory still haunted her. Mercedes proceeded to extract from her luggage small statues of the Virgin Mary, Saint Teresa, Saint Francis of Assisi and Buddha. She placed the statues in the corners of the room, lit candles, knelt in the middle of the room, and stripped. ‘Come here, kneel beside me, and get undressed,’ she urged. ‘Let the fragrant smoke and my prayers touch your naked body and protect you.’ The two naked women knelt and addressed each of the saints. Garbo fell into a deep trance and slept. When she awoke, Mercedes and she were lying together in bed.

We might as well be reading some 15th-century book about abbesses and marvels and spontaneously bleeding relics.

But huge squandering also went on. Thirty years were trifled away while she schemed at getting attention. The ‘greatest starfucker ever’, it turns out, was a fool. She was a pre-Enlightenment person in a post-Enlightenment age. She could never bring herself to give up on daydream or romance or superstition. The Garbo fiasco grew precisely out of this morbid resistance to insight. For theirs was fundamentally a clash of sensibilities. Along with everything else that made her great, Garbo was ruthlessly, corrosively modern, as thorough in her irony and disillusionment as Gibbon or Voltaire. Her comical habit of referring to herself in ordinary conversation as male – as in sentences beginning, ‘when I was a young boy in Sweden’ – was her own private Dadaist joke on the world, and symptomatic of her profoundly intransigent spirit. De Acosta, by contrast, was a throwback, a figment out of the Dark Ages, wedded to unrealities, unaccountably undead (and still perambulating) in an age of science and scepticism.

In this regard, surely the most haunting and pathetic item preserved in the Rosenbach archive is de Acosta’s family Bible, inscribed in her hand with verses from Matthew, including: ‘He that findeth his life shall lose it: and he that loseth his life for my sake shall find it.’ At some point in the 1930s, de Acosta began cutting out old fan-mag pictures of Garbo and plastering them into the Bible’s front matter. One or two of the photos are of Garbo kissing someone, the recipient of the kiss in each case having been carefully excised, so that the actress appears to look up, lips oddly pursed, into empty page-space. The result is a weird scrapbook, Countess Dracula’s Album of Sacred and Profane Love. By this point the ravening and battening had become crazy and compulsive. But at least for this (once-beguiled) reader it’s now impossible to care very much. Like most vampires and blood-suckers, Mercedes de Acosta was an incorrigible dolt. Best run a stake through her heart and have done with it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.