Conceived and researched during the 1990s, these two books nevertheless make important contributions to our understanding of today’s international turbulence and uncertainty. Taken together, they help unravel one of the deepest mysteries of American policy towards Iraq: namely, why dissent inside the US has been so tame and equivocal. Why have the keenest protests against Bush’s strategically unnecessary unilateralism come from the internationalist wing of the Republican Party (Brent Scowcroft, James Baker) rather than from the Democrats or the Left? Samantha Power and David Halberstam did not set out to solve this riddle, but they have unintentionally provided an important part of the answer.

Power was motivated to study the history of disappointing US responses to genocide by her indignation at the Clinton Administration’s belated reaction to mass killings in Bosnia, where she worked in the early 1990s as a young freelance reporter. She was understandably appalled by what happened after the carnage began in 1992: ‘Despite unprecedented public outcry about foreign brutality, for the next three and a half years the United States, Europe and the United Nations stood by while some 200,000 Bosnians were killed.’ The book’s bitterly ironic title distils her feelings about this period of inaction. It was Warren Christopher who called genocide ‘a problem from hell’, implying basically that butchery in the Balkans was a public relations fiasco for the Administration. Cynically or not, the West sat on its hands, refusing to undertake even relatively costless gestures, such as knocking out the emplacements around Sarajevo. This particular lapse reminds Power of the Allies’ refusal to bomb the rail lines into Auschwitz during the Second World War. The analogy is meant to sting. The Western countries that did nothing between 1992 and 1995 were the same ones that, with great solemnity, had opened museums to memorialise the Holocaust and, of course, had repeatedly promised ‘never again’.

To get some distance on the Bosnian catastrophe and to comprehend the dynamics underlying American non-intervention, Power decided to study the history of US responses to atrocities abroad. She returned from her historical quest with a tale of cowardice and mendacity, stretching from the massacre of the Armenians in 1915 to the slaughter of the Tutsi in 1994. Her basic theme is ‘America’s toleration of unspeakable atrocities, often committed in clear view’. It turned out that ‘the United States had never in its history intervened to stop genocide and had in fact rarely even made a point of condemning it as it occurred’. She hammers home the premeditated nature of US policy with instructive studies of Washington’s passivity in the face of mass murder in Rwanda, Cambodia and Iraq as well as Bosnia.

Here is a typical passage: ‘The Rwandan genocide would prove to be the fastest, most efficient killing spree of the 20th century. In a hundred days, some 800,000 Tutsi and politically moderate Hutu were murdered. The United States did almost nothing to try to stop it.’ Not only were no US troops dispatched or UN reinforcements authorised: no high-level US Government meetings were held to discuss non-military options, such as jamming Hutu radio broadcasts. No public condemnations were uttered. And no attempt was made to expel the genocidal Government’s representative from the Security Council, where Rwanda held a rotating seat at the time.

Endeavouring to remain hopeful even while detailing America’s refusals to rescue foreign victims of mass slaughter, Power alleges that pessimism of the intellect comports easily with optimism of the will. But the historical picture she paints is dark almost to the point of misanthropy. Basically, one US Administration after another stood idly by, feigning ignorance and impotence, while preventable genocide occurred. She freely reports this finding even though it blunts her indictment of the Clinton Administration, whose reluctance to intervene militarily on humanitarian grounds comes across, in the end, as exactly what one would expect.

Not the US alone, we are also given to understand, but every powerful nation looks first to its economic and strategic interests, embarking on missions of mercy only rarely and unreliably. All responses to injustice are selective, and the principles of selection are invariably tainted with the partiality of power-wielders towards themselves and their friends. During the Cold War, for instance, the US eagerly dwelt on Soviet violations of human rights. Today, by contrast, the US plays down Moscow’s behaviour in Chechnya, out of respect for the two countries’ shared confrontation with Islamic terrorism. Power is not the first to discover it: but, in international affairs, the factual distinction between ‘them’ and ‘us’ overshadows the moral distinction between just and unjust.

Another example of this shameful but persistent pattern makes arresting reading today. George H.W. Bush’s largesse towards Iraq outdid Ronald Reagan’s, even after Saddam Hussein’s murder of a hundred thousand Iraqi Kurds had been amply documented. The credits provided by Bush ‘freed up currency for Hussein to fortify and modernise his more cherished military assets, including his stockpile of deadly chemicals’. In 1989-90, Bush Sr gave financial support to the vicious dictator in Baghdad not only in order to curry favour with American farmers, eager to peddle their crops abroad, but also because of Tehran: that is, because the US President assumed platitudinously that the enemies of his enemies were his friends.

Homicidal rulers are sometimes toppled, it is true, but rarely by good Samaritans. Power summarises her dispiriting conclusion this way: ‘Unless another country acts for self-interested reasons, as was the case when Vietnam invaded Cambodia in 1979, or armed members of the victim group manage to fight back and win, as Tutsi rebels did in Rwanda in 1994, the perpetrators of genocide have usually retained power.’ But what about the decision of the US and its allies to intervene belatedly in Bosnia and, more rapidly, in Kosovo? According to Power, these are simply the exceptions that prove the rule.

The eventual decision to intervene militarily to halt the Balkan atrocities was the product of a coincidence of factors very unlikely to be repeated. For one thing, might does not even listen to right unless the latter occupies a fashionable address in Washington DC. In this case, according to Power, the influential American Jewish lobby, galvanised by TV images of emaciated white men behind barbed wire, set to work and put irresistible domestic pressure on the White House. Not universal morality but group politics cut the ice: ‘Jewish survivors and organisations put aside Israel’s feud with Muslims in the Middle East and were particularly forceful in their criticism of US idleness.’ And the apparent reason why ‘American Jewish leaders pressed for military action’ was that ‘the Bosnian war brought both a coincidence of European geography and imagery.’ To emphasise the decisive role played by ethnic particularism, despite all talk of moral universalism, Power adds: ‘one factor behind the creation of the UN war crimes tribunal for the former Yugoslavia was the coincidence of imagery between the Bosnian war and the Holocaust.’

Apparently, Clinton’s desire not to appear weak also influenced the US’s ultimate choice to intervene in the Balkans: ‘This was the first time in the 20th century that allowing genocide came to feel politically costly for an American President.’ Nato’s dread of losing its raison d’être and Europe’s anxieties about refugees combined with such domestic US factors to provide the necessary boost for a policy of humanitarian intervention. Such concerns gave the intervening states, or their leaders at the time, their own stake in military action. Moral conscience had been demanding intervention for several years. But only when political pressure built up simultaneously on several fronts did forcible intervention occur.

Before turning to her gruesomely detailed case studies, Power devotes three strangely sunny chapters to the story of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Here she temporarily discards her political tough-mindedness to extol the good intentions of Raphael Lemkin, the indefatigable Polish-Jewish activist who crafted the Convention and lobbied for its passage. She eulogises Lemkin as a hero of liberal internationalism, devoted to ending atrocities everywhere, if not to ensuring perpetual peace, by means of laws and treaties and international courts. She pays little attention, at this point, to the sheer improbability of Lemkin’s utopian project, given the harsh realities of international politics, but her uncritical approach to such idealism provides her with a moral pulpit from which to observe and condemn the indescribable savageries she is about to recount: just how rickety this utopian platform turns out to be is left for the reader to discover.

Approved by the UN General Assembly in 1948, the Genocide Convention came into force in 1951, and was guardedly ratified by the United States in 1988. Ratifying states are required to adopt legislation making genocide a criminal offence, even for heads of state. Trials for genocide must be held either in the country where the genocide occurred or at an international penal tribunal, if such a court is ever established. These and accompanying provisions at first sound anodyne and easily doable. But in fact the Genocide Convention represents an improbable attempt to modify several basic principles that have dominated international law since the Treaty of Westphalia. It aims, above all, to curb the sovereign right of national governments to decide, without being second-guessed by foreigners, what domestic threats they face and what responses, on their own territory, are available to meet such real or imaginary threats.

Before the Convention was ratified, the Western powers had intervened episodically to protect co-religionists in the Ottoman Empire, China and elsewhere. But international law did not expressly recognise any remedy against atrocities committed by a government against its own citizens within its borders. Because there is no unambiguous right without a reliable remedy, it follows that, under traditional international law, citizens had no right not to be brutally murdered by their governments within their state’s sovereign frontiers. Every government was master in its own house, and mass murder was an internal affair. As Power points out, this was a morally repulsive and even ‘maddening’ conception, although it accurately reflected political realities. The same doctrine prevailed even at Nuremberg. Although the tribunal there prosecuted German officials for crimes against Germans inside Germany, the proceedings did not satisfy Lemkin. The Nazis were charged first of all with the crime of aggressive war. And they were held responsible for atrocities against German citizens only when these crimes occurred after German armies crossed international borders. In other words, the Nuremberg precedent still assumed that borders were in some sense sacrosanct. Like the UN Charter, it still accepted the principle of national sovereignty as the basis of international order.

That Lemkin’s hopes of upending this traditional order and imposing humanitarian norms on powerful international actors have not been fulfilled is amply documented by the 1990s, a decade when copious talk of universal human rights mingled abhorrently with the most brazen crimes against humanity. The road to hell is apparently paved with good conventions. The decision to declare genocide a crime, against the older tradition of international law that exempted a state’s treatment of its own citizens within its own borders from the jurisdiction of international tribunals, has had little noticeable effect on the behaviour of homicidal maniacs in power. There are various reasons for this failure.

For one thing, the leaders of large and internationally powerful states such as China and Russia remain confident that, however they behave in, say, Tibet or Chechnya, they will not be dragged before the kind of international penal tribunal reserved for fallen tinpot dictators such as Slobodan Milosevic. For another thing, although cruel leaders of lesser states, faced with the threat of prosecution for genocide, may, it is true, be deterred, they are just as likely to cling ferociously to power whatever the cost in human lives. Stimulated to think ahead, inveterate adventurers may even plot to eliminate any witnesses who might testify against them. Power herself suggests that anticipation of future trials and fear of incriminating testimony may have encouraged Hutu officials to widen the circle of their killings. If this is true, it suggests that the effect of the Genocide Convention on the behaviour of bloodthirsty leaders is not only observably weak and erratic, but is in principle indeterminate.

As these chapters also reveal, the Genocide Convention defines mass murder from a unique and even morally contestable point of view. The Convention’s departure from Enlightenment universalism is already suggested by the origins of the idea of genocide in attempts to criminalise the massacre of Armenians: ‘Most Europeans identified with the Armenians’ suffering because they were fellow Christians. But when the Russians suggested condemning “crimes against Christianity”, it seemed too parochial, and the phrase “crimes against humanity and civilisation” was chosen instead.’ Since partiality may hide its face without losing its grip, this change in wording did not necessarily signal a shift in attitudes. Whatever international law stipulates on paper, crimes against whites and Christians still receive greater attention from Western powers than crimes against non-whites and non-Christians.

The Genocide Convention is one-sided not merely in its selective implementation, however, but also in its very conception. First of all, the Soviets succeeded in excluding mass murder for political reasons from the definition of genocide: ‘the law did not protect political groups. The Soviet delegation and its supporters, mainly Communist countries in Eastern Europe as well as some Latin American countries, had argued that including political groups in the convention would inhibit states that were attempting to suppress internal armed revolt.’ As a consequence, Power remarks, the death of ten million Africans between 1880 and 1920 as a direct result of Belgian colonialism might not have counted as genocide: ‘Leopold’s crimes were mammoth, but . . . they were not aimed at wiping out one particular ethnic group. Any and every African slave was vulnerable.’ Because the victims were of mixed ethnicity, their killings may have added up to mass murder, but not to genocide, as Lemkin explicitly conceived it.

As legally defined, in effect, genocide refers to the massacre only of certain communities. It is a crime committed not against members of ethnically or racially or religiously diverse groups but only against members of ethnically or racially or religiously homogeneous groups. For this reason, Power admits, the mass murder of two million Cambodians by the Khmer Rouge does not fit Lemkin’s definition perfectly, even though she, for her own reasons, includes that case here. According to the Convention Lemkin drafted and shepherded into existence, ‘If the perpetrator did not target a national, ethnic or religious group as such, then killings would constitute mass homicide, not genocide.’ This point often gets lost in discussions among non-specialists. The Genocide Convention does not criminalise attempts to destroy a multicultural community such as Sarajevo. It was not meant to cover a mass-casualty attack on ethnic, racial and religious patchworks such as London or New York City. It was drafted to protect homogeneous groups not heterogeneous groups.

Lemkin himself seems to have believed that killing a hundred thousand people of a single ethnicity was very different from killing a hundred thousand people of mixed ethnicities. Like Oswald Spengler, he thought that each cultural group had its own ‘genius’ that should be preserved. To destroy, or attempt to destroy, a culture is a special kind of crime because culture is the unit of collective memory, whereby the legacies of the dead can be kept alive. To kill a culture is to cast its individual members into everlasting oblivion, their memories buried with their mortal remains. The idea that killing a culture is ‘irreversible’ in a way that killing an individual is not reveals the strangeness of Lemkin’s conception from a liberal-individualist point of view.

This archaic-sounding conception has other illiberal implications as well. For one thing, it means that the murder of a poet is morally worse than the murder of a janitor, because the poet is the ‘brain’ without which the ‘body’ cannot function. This revival of medieval organic imagery is central to Lemkin’s idea of genocide as a special crime. Moreover, the idea that rape of a woman by a man of another ethnic background is essentially distinct from rape of a woman by a man of her own ethnic group implicitly treats the female body instrumentally, as a vessel reserved for perpetuating into the future an unalloyed racial stock.

All this is fascinating and disturbing. But the most eye-catching feature of ‘A Problem from Hell’ is Power’s palpable frustration with multilateralism and legalism. An important clue to this aspect of her thinking is the approval with which she cites Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle, two unilateralist hawks associated with the current Bush Administration. During the 1990s, they both urged US military intervention in Bosnia and Kosovo outside the framework of the UN and contrary to its Charter. Power thinks they were perfectly right. The Rwanda debacle was partly a result of UN dithering and incoherence. Indeed, the UN’s credibility had earlier been severely damaged on the streets of Mogadishu. In the 1990s, therefore, human rights advocates did not speak deferentially about the UN. On the contrary. Uncertain of their mandate in Rwanda and focused on self-protection, the hapless Blue Helmets allowed themselves to be disarmed before ten of their number were brutally murdered. Referring to the passivity of the US as the catastrophe unfolded in Rwanda, Power remarks: ‘The United States could also have acted without the UN’s blessing, as it would do five years later in Kosovo.’ Formulated more pungently, acting decisively sometimes requires a great power to extricate itself from the hopeless mishmash of multilateralism.

Liberals now lambast Bush daily for failing to act through multilateral institutions and in accord with international law. He is thereby gratuitously alienating potential partners from America’s just anti-terrorist cause, they explain. But that is not the way they felt in the 1990s. In those days, liberals were the ones calling multilateralism a formula for paralysis and inaction. They pointed out, for example, that the exquisitely multilateral EU, left to its own devices, was pitifully unable to mount a serious operation in the Balkans. Recently, when Morocco tried to seize a bit of Spanish territory, the EU proved unable to act decisively for the simple reason that its member states could not agree among themselves. (Colin Powell resolved the crisis by phone.) Today, on the question of Iraq, the three leading members of the EU have taken three mutually inconsistent positions. One could even argue that the US’s turn to unilateralism is a natural consequence of Europe’s embrace of dysfunctional multilateralism. For how can Washington act in concert with allies who are fused at the hip but cannot settle internal differences in a timely fashion? And how wrong was Bush when he suggested to the General Assembly in September that without US leadership and law enforcement capacity the UN risks becoming another League of Nations?

Be this as it may, the proponents of humanitarian intervention, in the 1990s, were among multilateralism’s least forgiving critics. Power writes in this spirit. Clinton embraced ‘consultation’, she tells us, whenever his Administration lacked a clear policy of its own. In that sense, too, multilateralism is a sign of weakness. When it comes to atrocities, she implies, the US should simply have told its allies what it was going to do. From the same perspective, she also comments unflatteringly on the Yugoslav war crimes tribunal. The tribunal was initially established, she correctly explains, in order to avoid taking military action. In emergency situations, more generally, legalism can prove as debilitating as multilateralism. Due process can get in the way of an adequate response to genocide. We need to move swiftly and flexibly against the worst international villains even if this means unleashing lethal force on the basis of hearsay testimony and circumstantial evidence: ‘an authoritative diagnosis of genocide would be impossible to make during the Serb campaign of terror.’ Indeed, pre-emptive deployment of troops on the basis of clues collected by operatives in the field might be the only way to stave off a Rwanda-style massacre. The very idea of a war against genocide probably implies a relaxed attitude towards mens rea: ‘Proving intent to exterminate an entire people would usually be impossible until the bulk of the group had already been wiped out.’ Careful observance of procedural niceties will impede any speedy response to an unfolding massacre.

Deference to public opinion is equally inappropriate, Power continues, especially when the electorate is self-absorbed, parochial and fixated on body-bags. One wonders if her lack of sympathy with the widely reported public aversion to military casualties might have anything to do with the infrequent human contact between human rights activists and the families of the grunts who would be asked to die to uphold vaguely worded international laws. In any case, she also suggests that chronically reticent military should be rolled over by morally attuned civilian leaders in order to confront wicked forces in the world. Faced with humanitarian atrocities in distant lands, any American official or citizen who claims to see shades of grey or two sides of the story, or who claims not to know exactly what is happening in the interior of a distant country, is probably feigning ignorance to deflect calls for action and to get the US off the hook. Some of those who declare murderous situations inside closed societies to be indecipherable by distant foreign observers are simply liars, while others are accomplices to genocide. If Power does not say exactly this, she comes close.

Needless to say, the 1990s advocates of humanitarian intervention are marginal actors on today’s political scene, with little or no influence on current policy. But that does not mean that their way of thinking has been without effect. They have, on the contrary, unwittingly muffled the voices of Bush’s critics. This is the principal relevance of ‘A Problem from Hell’ to contemporary political debates. Power helps us understand a neglected reason for the near paralysis of the American Left in the face of the pre-emptive and unilateralist turn in American foreign policy. The Democrats’ embarrassingly weak grasp of the differences between al-Qaida and Saddam Hussein and their election-year fear of being branded unpatriotic are not the only pertinent factors. Having supported unilateralist intervention outside the UN framework during the 1990s, liberals and progressives are simply unable to make a credible case against Bush today.

Formulated differently, the 1990s advocates of humanitarian intervention have unintentionally bequeathed a risky legacy to George W. Bush. They have helped rescue from the ashes of Vietnam the ideal of America as a global policeman, undaunted by other countries’ borders, defending civilisation against the forces of ‘evil’. By denouncing the US primarily for standing idly by when atrocity abroad occurs, they have helped repopularise the idea of America as a potentially benign imperial power. They have breathed new life into old messianic fantasies. And they have suggested strongly that America is shirking its moral responsibility when it refuses to venture abroad in search of monsters to destroy. By focusing predominantly on grievous harms caused by American inaction, finally, they have obscured public memory of grievous harms caused by American action.

To be sure, Power discusses the petty complicities of the US with various wicked regimes. The generous aid that Bush père provided to Iraq has already been mentioned. For similar reasons, to please China and displease Vietnam, ‘Carter sided with the dislodged Khmer Rouge regime,’ orchestrating a vote in their favour in the UN credentials committee. She also mentions other cases in which, for geopolitical and economic reasons, the US cynically consorted with the perpetrators of mass killing, including Nigeria in 1968 (one million Christian Ibo killed) and Pakistan in 1971 (almost two million Bengalis killed). But her principal stress throughout is on the immorality of the bystander who does nothing to prevent other peoples’ crimes. In 1975, for example, ‘when its ally, the oil-producing, anti-Communist Indonesia, invaded East Timor, killing between 100,000 and 200,000 civilians, the United States looked away.’ It is typical that she gives greater attention to this ‘looking away’ than to the weaponry and other active support that the US supplied, say, to Suharto ten years earlier, when he killed perhaps a million people in his campaign against the KPI.

The natural result of focusing on atrocities that the US did nothing to prevent is to nudge other forms of wrongdoing and miscalculation into the background. Above all, it helps the current Administration achieve one of its principal ideological goals – namely, to erase from public memory the chastening lesson of Vietnam. In a footnote, to be fair, Power recollects the US’s own crimes at Mai Lai: ‘Although not one villager fired on the US troops, the Americans burnt down all the houses, scalped or disembowelled villagers, and raped women and girls or, if they were pregnant, slashed open their stomachs.’ But the overall effect of the book is to blur such memories, to obscure how the use of US military force abroad, perhaps admirable in its original purpose, sometimes mires America in local struggles that it cannot master, radically weakens the democratic oversight that a chronically parochial public can exercise over a secretive military operation, involves our own soldiers in savage acts, and undermines the country’s capacity to deliver some modest help to distressed peoples elsewhere in the world.

If we are responsible for our incredulity, as Power claims, are we not also responsible for the credulity that our good intentions create in others? If human rights activists push an interventionist policy that cannot be politically sustained, what have they done? If the international community coaxes the Bosnian Muslims to sit unarmed in a ‘safe area’, but does not come through when Srebrenica turns into a shooting gallery, who is responsible for abandoning those in whom we have nurtured unrealistic dreams of rescue? Are we responsible when we awaken false expectations by earnest talk? Are human rights advocates responsible when they initiate a policy that they know cannot be sustained politically, given domestic indifference to foreign affairs and the paralysing array of political forces back home? Power mentions this problem, to be sure. In fact, she explains that, because the West had promised bombing, the Muslims of Srebrenica did not reclaim the tanks and anti-aircraft guns that they had turned over to the UN in 1993 as part of a demilitarisation agreement. But she does not draw out the implications of this appalling bait-and-switch story for her depiction of humanitarian intervention as a politically shaky but morally obligatory cause.

In a battle with ‘evil’, no means seem impermissible. In the midst of a humanitarian catastrophe, the downstream consequences of short-term strategies do not occupy the centre of attention. The ghastly sight of mutilated corpses disinterred from mass graves is psychologically incompatible with calculations about scarce resources, opportunity costs and trade-offs. That is what we mean by moral clarity. Max Weber called it the ethics of conscience. But a sickened heart does not necessarily exempt us from taking responsibility for what happens after we intervene. What if the side on whose behalf we bomb urban areas subsequently commits ethnic cleansing under our military protection? Even if it begins with moral clarity, humanitarian intervention may gutter into moral ambiguity once the interveners find themselves, as in Kosovo, on the side of ethnic cleansers or propping up an unseemly local ‘elite’ infested with gangsters and drug smugglers.

Putting an end to atrocities is a moral victory. But if the intervening force is incapable of keeping domestic support back home for the next phase, for reconstructing what it has shattered, the morality of its intervention is ephemeral at best. If political stability could be achieved by toppling a rotten dictator or if nations could be built at gunpoint, this problem would not be so pressing. Human rights cannot be reliably protected unless a locally sustained political authority is in place. But how well prepared is the United States for rebuilding a domestically supported political system in, say, Iraq, where a multi-ethnic society has, so far, been glued together by a regime of fear administered by a minority ethnic group? A functioning state can be built only with the active co-operation of well-organised domestic constituencies. It cannot be imported by an occupying military force. Where are such constituencies in Iraq? Do we believe that militarily powerful outsiders with minimal understanding of Iraqi society can conjure well-organised pro-democratic groupings out of thin air? Or is the Bush Administration, despite its rhetoric about democracy, planning to establish a government in postwar Iraq by, of and for the US military? The failure to think through, in advance, cogent answers to these questions is part of the dubious legacy bequeathed by genuinely well-meaning humanitarian interventionists to the considerably less well-meaning non-humanitarian interventionists who bestride the Potomac today.

Replete with colourful anecdotes, David Halberstam’s book also provides a measure of analysis and interpretation. His main story concerns US military interventions after the Cold War, with special focus on Clinton’s reluctant use of force in the Balkans. He says he wants to help us understand ‘the contradictions and the ambivalence of America as a post-Cold War superpower’. He therefore describes how the sudden collapse of the USSR and the 1990s economic boom led to ‘an era of consummate self-indulgence’, luring Americans into lowering their collective defences. Foreign policy, he explains, loses its focus in a time of peace.

The entertainment culture, we are also told, has gobbled up the American broadcast media, rewarding ‘journalistic feather merchants’ and sidelining the kind of serious reporting of foreign news that could help the US exercise responsibly its unparallelled global power. The flattering and teasing portraits Halberstam paints of personal friends, such as Richard Holbrooke, reveal the extent to which this is an insider’s tale, a story recounted by someone with enviable access to the Washington political scene. Based on long private conversations with the powerful, the book is meant to make readers feel that they understand the way Washington thinks.

Halberstam catapulted to fame in the early 1970s with The Best and the Brightest, his account of the US’s catastrophic involvement in Vietnam. He has written many other books in the interim, but it is not surprising that here, returning to foreign affairs, he still has a great deal to say about ‘the ghosts of Vietnam’. He writes very well, for instance, about the military’s lingering fear of being lured into an impossible quagmire and then being abandoned by a sauve-qui-peut civilian leadership. He is also eloquent about the psychological torment of Tony Lake and other onetime anti-war activists who came to power under Clinton and, faced with genocide, learned to jettison their youthful doubts about American military interventions abroad.

This brings us to the principal reason for reading Halberstam alongside Samantha Power. War in a Time of Peace inadvertently reveals the story of the author’s own dramatic metamorphosis. A beacon to the anti-war generation, Halberstam, too, re-emerged in the 1990s having shed his distrust of American power. He has gone so far in this direction that he seems genuinely dazzled by the high-tech weaponry he describes. The reason for this about-turn is important to notice. For he, like many others, sees in humanitarian intervention an irresistible moral cause that authorises the use of what he had once considered forbidden means. This same change of heart, incidentally, prepared him to compose a patriotic preface to his book after 11 September. He swaggers there about the ‘muscularity and flex in American society’ and informs the world that ‘our strengths, when summoned and focused, when the body politic is aroused and connects to the political process, are never to be underestimated.’

The Washington DC we discover in these pages, however, is not exactly the self-assured capital of a global empire. Muscularity and flex are not much in evidence. Instead, Halberstam’s Washington seems like a small town racked by palace intrigue, grandstanding, back-stabbing, information hoarding, careerism, cronyism, bureaucratic inertia, lack of focus and supine inattention. Sometimes decision-makers are excessively cautious, at other times they are madly reckless. We also hear of scandal-mongering, vested interests, tunnel-vision NGOs, obsolete mindsets, CNN-driven policy-making, and self-destructive envy for individuals of exceptional talent. In election years, politicians thrash around blindly in an attempt to humour or captivate public opinion. Overstretched policy-makers feign control when they are actually flying by the seat of their pants. Cabinet members appearing on Sunday morning talk shows are apprised of their own Administration’s policies only after placing frantic Saturday evening phonecalls.

Incoherence and strife, too, are ubiquitous. Tensions between civilians and the military run so deep that they seem cultural rather than merely a matter of turf. Political parties, Congress, the executive branch and the military are all internally divided as well as at war with each other. Halberstam’s ruminations on the ideological or normative basis of paralysis in US foreign policy are especially relevant today. Oversized egos are not the only sources of confusion and immobility. Even more important is the war of analogies: namely, the battle between conflicting narratives or interpretative frameworks. Which image will dominate American foreign policy over the next decade: Munich or Vietnam? What should we fear most: appeasing a dictator who will eventually strike us without warning or being dragged into a quagmire? In this ongoing struggle, there is something to be said on both sides. That it cannot be reduced to a battle between reckless warmongers and spineless appeasers is one of Halberstam’s wisest claims.

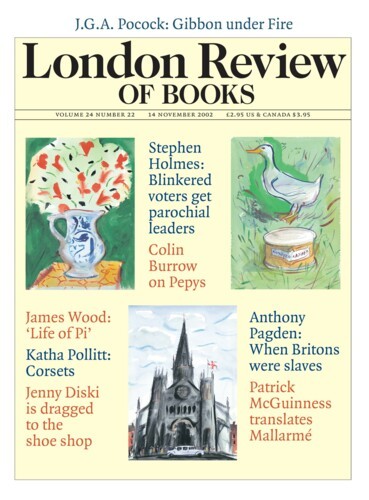

Dampened or disciplined by the Cold War, such conflicts flowered luxuriantly after 1991. Flummoxed by an illusion of peace, the US lost its foreign policy bearings. No one managed to formulate a comprehensive doctrine to replace containment and deterrence. Clinton’s unsleeping critics attributed the confusion to a leadership vacuum, to the inability of a domestically oriented President to frame foreign policy issues forcefully. But this problem cannot be laid exclusively at Clinton’s feet. In 2000 just as in 1992, a former governor with no foreign policy experience was elected to the Presidency by an electorate profoundly uninterested in the rest of the world. Intervention in the Balkans came so late for the perfectly democratic reason that ‘there was little in the way of a constituency, either in or outside the Government, for taking military action against the Serbs.’ Blinkered voters get the parochial leaders they want rather than the worldly leaders they presumably need.

Revealingly, Halberstam’s book illustrates several of the shortcomings it purports to dissect. It is a Washington-centred study, for one thing, in which voices from Europe or the Balkans are almost never heard. This is not necessarily Halberstam’s doing. He spoke to everyone who is anyone in Washington and apparently no one ever mentioned that people elsewhere in the world see things somewhat differently from the way Americans see them. In his concluding remarks, he rather defensively explains: ‘This book was always premised to be about America, not about the Balkans or any other foreign country.’ To study the use of US military force abroad, intimate knowledge of our allies or even of the countries in which American forces are deployed is apparently optional. Why should the student of American intervention know more about the rest of the world than those who plan and carry out the action?

This attitude may explain why Halberstam leaves unmentioned various interpretations of Nato’s Kosovo operation that are widely diffused in the region itself: for instance, that Nato did exactly what Milosevic wanted and that the latter’s only mistake was to underestimate the fatigue of the Serbian population that would afterwards drive him from office. The claim that Nato was reading from a script written by Milosevic builds on the premise that, before the war, Kosovo presented Belgrade with an irresolvable dilemma. As a poor Albanian province where few Serbs wished to live, it could not be integrated into Yugoslavia. But Milosevic could not simply grant independence to Kosovo, because of the province’s critical role in Serbian national mythology. The ideal solution, from his point of view, was to have Kosovo ripped away by Serbia’s overwhelmingly powerful foreign enemies, allowing him to cut loose the province while appearing to be an unwavering defender of national honour. My point is not that this interpretation of events is accurate or even plausible, merely that it is a commonplace in the Balkans. Halberstam’s failure to mention it suggests that what is commonplace in the rest of the world can be totally unheard of in Washington DC.

Today, the US is steadily cutting back its commitment of troops and treasure to the Balkans, despite the unsettled situation in Macedonia, and handing over responsibility to the uncertainly prepared Europeans. Here again Halberstam follows Washington’s lead. He, too, turns away from the region, revealing scant interest in the aftermath of military intervention. His few remarks on Bosnia today, for example, indicate a shaky grasp of what it means for international authorities to try to impose a multi-ethnic democracy on three peoples who, after the horrors of 1992-95, have no stomach for knitting together a common life. Having canvassed the opinions of America’s foreign policy elite, Halberstam has nothing to say about managing the consequences of US intervention in the Balkans. His book therefore helps us see the world from an increasingly prominent point of view. It provides a window into the mindset of those for whom ‘regime change’ means destroying a wicked system, full stop, rather than replacing a rotten government with a moderately better one that has a sporting chance to endure.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.