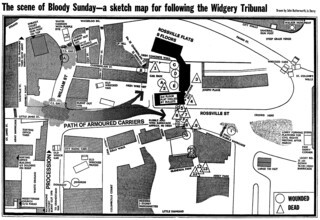

On the night of 30 January 1972, Murray Sayle was sent by the Sunday Times to Londonderry to report on the fatal shooting of 14 unarmed civil rights marchers by British Army Paratroopers. The article he wrote diverged from the official line; it was never printed. Twenty-six years later, his lost copy was unearthed by the new Inquiry. In what follows, he returns to Derry to give evidence. His original article is reproduced in full, along with a map marking the locations of the dead and wounded, and a memo Sayle wrote to the editor of the Sunday Times when the article failed to appear.

Belfast City Airport in early June, all fashionable glass and girders, might have been anywhere the dollar lands. On the baggage carousel the circling aluminium cases and tripod of a TV crew reassured us that we were still in the real world. The tall, London-based CNN presenter Richard Quest, in tailored trenchcoat, waited impressively for his gear. CNN was here for some really significant story – the marriage of Sir Paul McCartney and anti-landmine campaigner Heather Mills, perhaps; a shade less probably, the wedding in St Eugene’s Cathedral, Londonderry, of Gráinne, daughter of Northern Ireland’s Education Minister Martin McGuinness (not yet knighted for his varied public services, but it’s early days), and Sean ‘Harpie’ Hargan, the Derry football hero. The TV wasn’t there, we thought wistfully, to cover us, or the long-running story that had brought us back to Northern Ireland after thirty years: the Inquiry into the fatal shooting of 14 unarmed civil rights marchers by British Army Paratroopers in Derry on 30 January 1972 – the ‘Bloody Sunday’ of Irish legend and British embarrassment.

Ghosts from a painful past – myself from Japan, my friend, colleague on the Sunday Times and journalistic partner on Bloody Sunday, Derek Humphry, from Eugene, Oregon – had flown in at the invitation (and expense) of HMG to help the Bloody Sunday Inquiry in its renewed investigation into what had happened on that never-forgotten, never-forgiven day. Muzak crooned in the arrival hall, stalls offered stuffed leprechauns, Guinness T-shirts and ‘Kiss Me I’m Irish’ buttons. Passengers chatted over caffe latte and croissants. Could this be the Ulster I last laid eyes on thirty years ago? Where were the sandbags, the razor wire, the sniffer dogs of yesteryear? What had become of the intimidating Royal Ulster Constabulary and their ever-ready automatic rifles? All is changed, changed utterly, I noted with borrowed eloquence; a terrible blandness has taken over.

The road out of Belfast took us through neat suburbs fringed with lawns and gardens. The man with the mortgage, we decided, is rarely the man with the mortar. Belfast calls itself the City of the Titanic, as indeed it was, but it has clearly broken out of the dying North Atlantic trading economy whose long decline, and the consequent sectarian battle for working-class jobs, was the economic basis for the current cycle of the Troubles, dating from the hungry 1960s. The Harland and Wolff shipyard, once the busiest in the world, now refurbishes the odd ferry and tugboat. But Belfast and the North generally seem to have found new sustenance in handicrafts, high-tech start-ups, light manufacturing and above all tourists, both history-hunting Europeans and the dollar-laden Ulster diaspora of America, Canada and Australia. The British (and Irish) Isles are fast becoming a theme park for all English-speakers, and picturesque, unpolluted Ulster is finally getting some of its rightful cut. Massive EU subsidies and London-financed public works (some Catholics call them ‘conscience money’) have helped. Compared with the economic disaster area of the 1970s, and the even bleaker early 1980s, the Six Counties are doing nicely.

Not that passion is altogether spent. Otherwise there would be little justification for the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, which has already lasted two years and cost a reported £50 million – with two more years ahead, it seems likely to top the £80 million poured into the DeLorean sports car fiasco. To what end? Violence routinely erupted in inner Belfast during our visit, and the Loyalist (meaning Protestant, in the tribal sense) paramilitary boss Mark ‘Swinger’ Fulton, his life’s work in ruins, hanged himself in Maghaberry Prison, Co. Antrim. Emerging into the smiling farmlands south of Belfast we sped, on an excellent new road, between flagpoles alternating the Union Jack and the Red Hand of Ulster, which might have been there to mark the Golden Jubilee, and might not; and then, in noticeably poorer country, Irish Republic tricolours, their green-white-orange optimistically symbolising reconciliation between Catholic and Protestant. Signs reading UDA and RIRA (both, in our understanding, illegal organisations) suggested that Ireland is not quite there yet, as did our first roadblock, between Armagh and Omagh, and thus in debatable territory. We were in the right country after all, we decided, faintly miffed to be waved through. Too old for terror? The new Northern Ireland Police Service, in pale green shirts, were looking up the tailpipes of pulled-over cars, but the flavour was more ritual than real, we thought. They even smiled at us.

We bowled into Derry at lunchtime, in a chilly drizzle. The official guidebook calls it ‘Londonderry (also known as Derry)’ and signposts cautiously read ‘LDerry’. Many locals refer to it affectionately as Stroke City. The Derry part is the Irish word dáire, meaning ‘wooded island’. The London prefix dates from 1613 when James 1 granted a charter to the Society of Governors and Assistants, London, of the New Plantation of Ulster, known then and now as the Honourable The Irish Society. The Hon. The Irish Society was strictly a business proposition, like the East India Company, and being surrounded in Derry, as the Protestants still are, by fierce native Irish, they reckoned a stout wall would be a good investment. The walls of Derry still stand, still belong to the Hon. Society – which remains discreetly in business in the City of London – and figured prominently in the events of Bloody Sunday, as the Inquiry has been hearing.

A prosperous trading outpost, Derry attracted people too numerous, or of the wrong religion, to live inside the walls. The Protestant planters and their co-religionists settled on the right, in both senses, bank of the River Foyle, a well-situated salubrious suburb called Waterside. The native, and therefore Catholic, Irish came to live under the city walls in the Bogside, whose name confirms that it was not the most sought-after location in all Ulster. The action of Bloody Sunday took place in the Bogside, overlooked by the walls, and it was in the then nearby City Hotel that the press, including myself and Derek, stayed, drank and worked untangling Bloody Sunday. But the old City Hotel was blown up in 1974 and its site is still vacant – some trouble about who owns the utilities underneath. A new, four-star City Hotel is due to open nearby in August this year. Meanwhile, the Inquiry put us in the Quality Da Vinci’s, part of a standardised, globalised, American chain.

Raining or not, our first order of business was a nostalgic, memory-refreshing visit to the scene of the shootings, marked on the tourist maps as Free Derry Corner and the Bloody Sunday Monument. Most of the familiar buildings and the narrow alleys around them have gone, but the killing ground is still there, etched into Irish (and my) memory. The house-ends facing the Corner have giant murals in powerful, Guernica-style black and white. One shows a body lying lifeless on the pavement below. Another depicts Bernadette Devlin MP, as she then was, throwing down stones to build a barricade. Another has a British soldier breaking into a house with a sledgehammer; while on the house-end next door a Republican hero stands beside a gaunt, suffering Christ. The effect is that of a secular Stations of the Cross.

Near the wall announcing ‘You Are Entering Free Derry’ is a roll of the IRA lay saints who have starved themselves to death in British captivity down the years, from (as I read my rain-stained notes) Vol. – Volunteer – Thomas Ashe, who died in Mountjoy Prison 25 September 1917, to Vol. Michael Devine, INLA, who died in the Maze 20 August 1981. Above is a dove of peace caged in barbed wire; below the quote: ‘I’ll wear no convict’s uniform, nor meekly serve my time.’ Less ringing, and not attributed to the IRA, is the nearby Bloody Sunday Monument itself, a column on a podium with, when we were there, a wreath in the tricolour of the Irish Republic. The face of the column has a list of the dead, a tinted version of the Sunday Times map, and underneath, the terse legend ‘who were murdered by British Paratroopers 30 January 1972’.

Alongside the list of names is an admonition: ‘A debt of justice and truth is still owed to the victims, to the bereaved and to the people of Derry. The British military, the British judiciary, the British Government and the Stormont regime – all must accept responsibility for Bloody Sunday and its consequences. Only then can the wounds of that day finally be healed.’ Walking back, we saw that the Bogside and its environs are dying. Houses are vacant, pubs shuttered, betting shops closed. All over Ireland the old working class is becoming middle class, and the Derry Bogside is no different. Bogsider Martin McGuinness at his daughter’s fashionable wedding is staying in step with the aspirations of the people he leads.

Over dinner at Da Vinci’s, distinctly upmarket from the fish, chips and suet pudding of the old City Hotel, we discussed some implications. The IRA monument speaks bitterly of the past, of Terence MacSwiney, Bobby Sands and the long line of Irish Nationalist martyrs. The tragic Celtic hero and the physical force Republicanism he inspires is passing into history, but he will be remembered for a long time yet. His cause, however, is fast losing whatever appeal it had to the living, and to generations to come. The gun, whichever side uses it, is not going to decide the destiny of Ireland. The Bloody Sunday Monument strikes a rather different note. It speaks of the future, of possibly healing wounds, even of the conditions under which that could happen. Maybe, we decided, there was some point to our long journey beyond evening old scores and setting a twisted record straight. We turned in early, ready for a long day in court.

The Guildhall stands on flat ground between the city walls and the River Foyle, well away from the Bogside. Begun in 1890, destroyed by fire in 1908 (accidents can happen, even in Derry), it was rebuilt in the imperial neo-gothic style and reopened, much as it is now, in 1912, the year of the Titanic, when the North Atlantic economy was at its zenith and Great Britain was the world’s sole superpower. Witnesses are inspected by a marble Queen Victoria as they enter, sharp at nine, and pass through the metal detector with its even more penetrating gaze. The lift, however, is a creaking Edwardian museum piece. Upstairs, we get a nervous cup of tea and last-minute advice from the helpful Witness Liaison Team of lawyers and Northern Ireland Office civil servants. Yes, we can affirm, like principled people, instead of swearing by Almighty God; yes, the proceedings are judicial and thus privileged like any court hearing; yes, we can lunch together as long as we don’t discuss our evidence. Then I am called to the witness stand, and Derek goes off to the public gallery to listen. Later, when he testifies, we will reverse our positions.

The Guildhall as fitted out for the Inquiry is quite a sight. The high vaulted ceiling soars above magnificent stained glass windows glowing with harps, crowns and Union Jacks: mementos of the Home Rule that was delayed by the First World War, to be followed instead by the Rising, Partition, and all the capitalised Troubles that eventually brought us here. It looks like a C of E garrison church minus regimental flags, but only down to floor level. Instead of pews and prayer books the floor of the hall is a dense crowd of lawyers and their clerks and assistants, half-hidden by the computer screens at which they all sit. It could be a stock exchange, or even William Hill’s. Bigger screens let the spectators follow the proceedings and, via a landline, do the same for the media in their own separate room where, at the touch of a button, they can get interesting passages printed out from the simultaneous transcript marching across the screen. Reporting was never as effortless as this, at least technologically, in the days of the real Bloody Sunday.

Testifying was, as much of modern life, like watching TV. The chairman, Lord Saville, politely introduced himself and his two colleagues of the tribunal, Justices William Hoyt of Canada and John Toohey of New South Wales, the last a member of a well-known Catholic family of lawyers, journalists and brewers. All three wore business suits and asked occasional sharp questions. Behind the bench loomed the ninety-odd volumes of Widgery Tribunal transcripts1 and the two hundred-odd days of this one so far – well over two million words, and much more to come. Counsel assisting the Inquiry, Christopher Clarke QC, acting as a kind of master of ceremonies, opened the proceedings by saying that everyone present had read my various witness statements (and, later, Derek Humphry’s) and that he and other counsel representing interested parties had some points to clear up. My witness statement then appeared on the big TV screen in front of me, and a red arrow danced over the page marking the sentence under discussion. When the scene of Bloody Sunday was mentioned a virtual representation of the Bogside as it then was flashed up, and the arrow roamed over its features as they were mentioned. The map shown below followed, then statements from other witnesses with more arrows. Two years ago this was the most advanced technology for conducting judicial proceedings in the world, and may still be – at least until the many foreign lawyers who have come to study it can produce their own versions, minus, of course, the late-imperial splendour of the Guildhall.

My evidence and cross-examination concerned the unpublished article and memo reproduced on the following pages, and can be read in toto on the Inquiry’s website www.bloody-sunday-inquiry.org.uk, which also defines the Inquiry’s broad brief: to investigate the events of 30 January 1972 and relevant circumstances. The Inquiry is not, however, a Truth and Reconciliation exercise on the South African model. Immunity from prosecution in return for truthful testimony was discussed early on, and rejected. By any reading of the conflicting evidence someone has to be guilty of perjury at least, and probably graver offences as well. The Inquiry therefore hides under its genial tone some of the adversarial aspect of a trial, or rather of many trials: of the IRA; of the Army, from the high command down to individual Paratroopers; of the media; and of those involved in authorising and justifying the operation, extending as far as the late Lord Widgery and the frail Edward Heath, British PM at the time, who has agreed to give evidence when the Inquiry transfers (and re-creates its technology) in Central Hall, Westminster, later this year, to hear what amounts to the Army’s case for the defence.

Are the usual penalties for perjury applicable to evidence given to the Inquiry? Does the normal protection against self-incrimination apply? I have not found firm rulings on these matters, and the imprecision is, I think, deliberate. Nothing like the Bloody Sunday Inquiry has ever taken place in Britain or a Commonwealth country before, and there are no precedents. No Royal Commission or equivalent has ever had its final findings reopened, for obvious reasons. While it is insisted that the present Inquiry is not trying to re-Widgery Widgery, the name of the Lord Chief Justice crops up constantly, and for good reason. The new Inquiry addresses exactly the same questions Lord Widgery did, and for that matter the ones we faced in the confused few days after Bloody Sunday, before his Tribunal was announced and reporting ended. Was there, or was there not, an Army plan to arrest those at the head of the civil rights demonstration? Was a gun battle with the IRA expected, and provided against? Were civilian casualties expected, and was the illegality of the march an element in accepting that risk? (As I said in my evidence, death is not, as far as I know, the penalty for illegally demonstrating in a British city.) Did the anticipated firefight take place? Which officer satisfied himself that the IRA were indeed present, and gave the order to execute the plan? Based on what intelligence? At least a thousand close eye-witnesses were present, but none saw the whole action. In the end only the Army and the IRA can shed light on these questions. Our article presents, in summary, evidence for the case to be answered. This, I believe, was why Derek and I were called.

I was therefore not surprised to be sharply, and skilfully cross-examined by Edwin Glasgow QC, counsel representing a number of the soldiers. I hope he will forgive me for saying that he deployed sarcasm, can-you-please-answer-yes-or-no and other classic devices for rattling hostile witnesses. The exchange can be read on the Inquiry’s website, but an extract will give the flavour:

MR GLASGOW: Mr Sayle. I know it is a long day; did any civilian give you any account of seeing any other civilian with a weapon, or shooting on that day other than the account you had of the .38 pistol at William Street, or the firing that took place late in the day after the Army had effectively ceased –

A. I do not recollect anybody saying that, I do not recollect it.

Q. If they had, presumably as an honest journalist you would have recorded it?

A. (Witness laughs) Yes –

Q. You shrug and laugh, but did you take it that seriously?

A. I am flattered that I am described as an honest journalist, I expect you are not wholly sincere about that, but never mind. No, of course, but we are discussing here what I was trying to do, looking for serious – people can be mistaken about what they see, right, particularly civilians when there is shooting going on, and so on. I have no recollection because otherwise it would have occurred in our piece.

And so on. Derek, in his evidence, confirmed my account of how our article was written. Like many journalists he declined to name either the head of the Provisional IRA in the Bogside on Bloody Sunday, or the young woman who was present when the PIRA decided to do nothing as the shooting broke out, in both cases on the grounds of preserving the confidence of sources. As he concluded his testimony Lord Saville informed him that there was a possibility that he would be asked to return and required to give these names, ‘and you would be entitled at Government expense to legal advice and representation.’ ‘I hear you, sir,’ Derek said.

Driving back to Belfast through the politically unpolluted, flag-free Antrim moors, we discussed the implications. How, or what the Inquiry will find, or even when, we have no idea. What responsibility any of the parties indicted on the Bloody Sunday Monument may accept we cannot predict, or whether there is any prospect of wounds healing any time soon. Proud father Martin McGuinness, for one, is co-operating with the Inquiry, which may indicate that the Nationalist mainstream would like to undercut its own irreconcilables’ best argument, and move forward. At least, everyone in Ireland can see that, unlike Widgery, the Inquiry is ready to listen to anyone and everyone, for as long as it takes. The vast majority, North and South, hopes for reconciliation, at home and over the Irish Sea. This prospect alone, we thought, goes some way towards justifying the expense, and our own small part in it.

Unseen for thirty years, the two documents that follow are published, exactly as written, for the first time. The map, intended to illustrate the article by Derek Humphry and myself, was published in the Sunday Times a week after Bloody Sunday, but without the article it conveys little meaning. The intra-office memo from myself to Harry Evans, then editor of the Sunday Times, and other colleagues at the outstanding paper for which both Derek Humphry and I then worked, has never been published before. At a minimum, the two documents add to the historic record.

On the night of 30 January 1972, Harry Evans telephoned me at home in London and instructed me to proceed to Londonderry as soon as possible to report on the deaths of 13 civil rights demonstrators,2 for publication the following Sunday, 6 February. He added that Derek Humphry was also going and that other colleagues might be joining us as the story developed. Humphry and I arrived late that night and booked into the City Hotel. The following morning, after a quick reconnaissance of the area of the shooting, Humphry and I drew up the plan of investigation I report in my memo of 19 February 1972.

I was at the time the paper’s most experienced war correspondent and had just returned from Vietnam. I had had considerable experience of disputed civil-military clashes in such places as Israel, 1967, Prague, 1968, Jordan (Black September), 1970, and Bangladesh, 1971. I had also covered Northern Ireland extensively, beginning in 1965, and in particular the riots that followed the internment of IRA suspects and others in August 1971. I had never been in Londonderry, however. Humphry, on the other hand, had often worked in Derry and had developed many contacts on both sides, particularly in the predominantly Catholic Bogside. We divided our investigation as described in my memo, conveyed our findings to the Sunday Times artist John Butterworth, wrote the report together in a room at the City Hotel, and filed it by telephone on Thursday 3 February. The next day the Widgery Tribunal was announced, making meaningful reporting on what had happened sub judice. Word reached us late on Friday 4 February that the article would not be published, although the Butterworth map and many photographs by the young French photographer Gilles Peress appeared in the Sunday Times on 6 February. Humphry returned to London and I remained in Derry, as described in my memo. I have not subsequently discussed the non-publication of the article with Harry Evans, although he did tell me in New York in 1999 that he had not read it when the decision was made.

The copy I wrote in Derry was discarded, or lost, as I assumed that the text would be on file in London. But I failed to find it in the Sunday Times office after my return from a new assignment in Pakistan, despite careful searching by myself and my then girlfriend, long since my wife. The report was not among the documents deposited in the Public Record Office in Kew after the Widgery Inquiry, and neither Humphry nor I was called to give evidence to Widgery. Twenty-six years later, in February 1998, and much to my surprise, the long-missing report spat out of my fax machine in Japan. The sender was a Derry academic, Dessie Baker, who had been present at Bloody Sunday as a teenager and has since been active in the long search for the truth of the incident. The document was not in the form we had written it, nor in the format then used by news copytakers, but had been retyped, perhaps for some legal purpose. Baker thought it might be a forgery. However, Humphry and I instantly saw that it was word for word what we had written. Baker explained that it had been found, by whom he did not say, among the records of the National Council for Civil Liberties held at Hull University. I have checked with the librarian, Bryan Dyson, who confirms that the report is in the NCCL file, but neither he nor Liberty, the successor to the NCCL, is able to say how it got there.

With our permission, Baker published much-abbreviated extracts from the article in Fingerpost, a small magazine covering the Catholic community in Derry, in April 1998. Baker also published a series of e-mails I sent him setting out my views on the importance of our article. ‘Whether we were right or wrong all those years ago doesn’t matter to either Derek or myself now, from a personal or professional viewpoint,’ I wrote. ‘We are far away now, and busy with other things. But what we [the Sunday Times] had already managed to do in Northern Ireland, and what we did not manage to do on that occasion, has long weighed on my mind, and I think on Derek’s, too.’ On the non-publication of the article Baker quoted me again: ‘Murray Sayle does not blame Harold Evans for not publishing the story: he said in 1992 that he “did not carry the editor’s heavy responsibility and the law is the law.” However, he does think that “such publication might have saved much subsequent bloodshed.”’ In the same exchange Baker quoted me again. ‘If the official explanation – that the Paras were sent to Derry to “control hooligans” and were ambushed by the Provisional IRA – was remotely credible then we would not be having this correspondence. There must be some other explanation. There are only two that are remotely possible: a deliberate massacre or a monumental bungle. There is the fork in the road.’

The Fingerpost article came to the attention of the reopened Bloody Sunday Inquiry, and in December 1998 Humphry and I were invited to London to make witness statements, the substance of which is in my memo. In mid-1999, Daniel Lee, assistant solicitor to the Inquiry, informed me that he had discovered the memo in a ‘trawl’ of documents sent to the new Inquiry by the present Sunday Times management, and asked whether I could identify it. Indeed I could, I replied. The memo was then added to the report as the documents I would be asked to identify to the Inquiry. More recently, I was asked to identify the Butterworth map as the one mentioned in my memo, which I was able to do. As I told the Inquiry, I have heard no reason to change the argument of either our unpublished report or my memo, and much to confirm their conclusions. I hope they may help bring Northern Ireland a little closer to peace and lasting reconciliation.

The Unpublished Article

Copy filed 3 February 1972

Murray Sayle and Derek Humphry

To understand the origins of the massacre we need to follow the four separate and sometimes twisted threads which met at Rossville Street. They are:

1. The inner conflicts of the anti-Internment movement among Ulster Catholics, deeply split about how to oppose a policy which every Catholic in Ireland thinks is wrong. 2. The changing attitudes of the IRA towards peaceful protest. 3. The fluctuating efforts of the Faulkner Government to appease the right wing of the Unionist Party. 4. The development by the Parachute Regiment of a plan to eliminate the IRA leadership in Londonderry – which in the result disgraced the Regiment’s record for a very long time to come and presented the IRA with the most resounding moral victory they have had since 1916.

Operating independently of each other, these four strands finally met on the bloody pavement of the Bogside last Sunday.

The Army’s version is not only denied by every eye-witness we have spoken to, many of them not Catholic and/or not Irish; it fails completely to answer any of these difficulties: we can find no evidence that any shots, petrol or nail bombs were fired at the Army, or that any of the crowd of civil rights marchers were armed; no wounded soldiers have been produced and none were shot; none of the wounded survivors of the shooting, supposed to be IRA suspects if not members, were searched; no guard was placed over them at Altnagelvin Hospital; we can find no trace of the two alleged by Army spokesmen to have admitted that they were armed, and no trace of arms; four of the dead men and two of the wounded were shot in the back or from behind.

1. Anti-Internment. There were two major movements: the Northern Resistance Group, which evolved out of the People’s Democracy, and stars Bernadette Devlin MP and her one-time militant student friends from Belfast University. The NRG staged a march the day before Bogside, retracing the route of the original civil rights march in 1968 from Dungannon to Coalisland. This march, at which there were British soldiers present but no violence, was illegal – the Faulkner Government’s six-month ban on marches does not expire until 9 February and will be renewed – and was considered a moral victory for the Catholic anti-Internment movement. The fact that it took place at all enraged right-wing Unionist opinion.

The next day, last Sunday, another illegal march was planned for Londonderry by the rival of NRG, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association. To the extent that it has any political direction at all, NICRA is principally under the influence of the Northern Ireland Communist Party and the official wing of the IRA. The NICRA has never had much support in Derry – it has in fact only six paid-up members in the Bogside – and in order to stage a meeting after last Sunday’s march (the meeting never took place) the organisers had to import both a chairman (Kevin McCorry from Belfast) and a principal speaker (Rory McShane from Newry, supported by Lord Brockway from London).

The leadership of the march was thus on the weak side, as Ulster political demonstrations go – which may have played a part, although a very small one, in the subsequent disaster.

However, passions against Internment continued to run high, and the march and planned meeting attracted at least ten thousand people – more than two-thirds of the inhabitants of Bogside, with many visitors from around Derry and over the Border.

Bogside people both feel passionately about Internment and love marches, and many people joined on the spur of the moment: as the procession passed Brandywell Recreation Ground where the Derry Harps were playing football against Letterkenny Rovers both teams abandoned the game and joined the marchers.

2. The march, which was evidently going to be a great success, posed a problem for both wings of the IRA in the Bogside.

The IRA has never had much success in Londonderry until last Sunday. Catholics in Londonderry, who are in the majority, do not fear attacks by armed Protestants; in the past their main fears were a punch-up with the police after the annual Orange March on 12 August. With the Irish Republic only a few miles away, they have never felt surrounded and cut off and at the mercy of Protestant pogroms as have the Catholics in Belfast, although their complaints against gerrymandering and discrimination were even louder, and these the IRA had no answer to.

The quasi-intellectual, diluted Marxist approach of the Official IRA had little appeal for the Bogside people, and the movement barely existed in Derry until Willy Kelly of the Provisional IRA, boss of the New Lodge estate in Belfast, and his lieutenant Barney Canaven arrived in the Bogside in June last year to organise the movement. They had an unexpected bonus when two Bogside men were shot by the police the following month – Cusack (certainly not IRA) and Beatty (very doubtfully so).

Internment last August caught one important Bogside IRA leader, Sean Kenny, but because most of his comrades-in-arms had just joined they were on no one’s list of suspects and few were caught. Internment was rather seen by Bogsiders as an arrogant gesture by the Faulkner Government and as such bitterly opposed.

So both IRA wings decided they could hardly abstain from last Sunday’s march, and both decided to attend – without their guns. This decision, in some distorted form, got through to the ears of British Army Intelligence, probably through RUC Special Branch informers.

3. But the imminent (and illegal in Stormont eyes) march posed a particular problem for Brian Faulkner. Derry shelters some of the most bigoted and reactionary of all Orangemen: what Nuremberg was to the Nazis, Londonderry the Maiden City is to the Orange militants and die-hard Unionists.

A particularly noisy group, led by a Protestant clergyman, calls itself the Democratic Unionist Association (the ‘democracy’ of the title is the idea that Protestants have the right to rule Northern Ireland for ever because the Border has been drawn to give them a majority). This movement also planned a march for last Sunday, as a counterblast to the NICRA march from Bogside, which was to have culminated in a meeting in Guildhall Square (a no man’s land, by Londonderry custom). The day before Bogside, the Democratic Unionists issued a statement (published on Saturday night in the Belfast Telegraph) that after ‘consultation with security forces’ they had called off their Sunday march after being assured by Brian Faulkner that the civil rights march would also be prevented, if necessary by force. Faulkner, in other words, had got off a Protestant extremist hook by promising to get tough with the Catholics – the type of compliance which has spilt rivers of blood in Northern Ireland in the past fifty years.

4. The last strand was supplied by the British Army, and notably by the Parachute Regiment. In recent weeks the Army has been claiming that it was winning the military confrontation with the IRA, ‘flushing out the gunman’ and so on. These claims have been made so regularly since Internment that few people have taken them seriously – but evidently both Brian Faulkner and Edward Heath did.

The military appreciation which has been going to Faulkner and Heath in past weeks is that the IRA is all but beaten in Belfast, where indeed there have been no serious riots since the weeks of Internment, and where the Parachute Regiment has claimed that its tight street-fighting tactics, built on delivering hard, unexpected blows at high speed to groups of IRA suspects, have achieved success.

This, according to the military planners, left only one major problem: the nest of IRA militants in the Londonderry Bogside. Military Intelligence asserted that there were about eighty hard-core militants; if they were killed or locked up, the IRA problem would be, according to the reports, as good as over.

But tactics were difficult. If one of these men were ‘lifted’ in a surprise dawn raid, the other 79 would flee over the Border, only a few miles away. If the Army invaded the Bogside in strength, a blood-bath like that of the Ardoyne in Belfast last August would probably result, and in the ensuing political protest British Embassies might be besieged or burned all over the world.

The Parachute Regiment staff planners believe they had the answer in the last weeks of the old year – a solution which in fact produced a massacre.

The idea – worked out, we believe, by Lieutenant-Colonel Derek Wilford on lines of thinking propounded by Brigadier Frank Kitson, British Army counter-insurgency expert – was based on the military principle that the way to bring your enemy to battle is to attack something that, for prestige reasons, he will have to defend: the Germans attacking Verdun in the First World War or the same firm attacking Stalingrad in the Second. Brought to battle, he will then be annihilated by superior strength.

The civil rights march, the Parachute Regiment planners believed, was just such an objective the IRA would have to defend, or lose its popular support in the Bogside – either way the IRA would be finished.

If the IRA gunmen could be induced to stand and fight while other demonstrators fled, a snatch squad – but it would have to be a large one – would be able to kill them or take them in. So, for some weeks the Paras have been drilling and rehearsing the company-size snatch squad – at about one hundred men, the biggest one ever used in the present Ulster fighting.

So it all came together: the Civil Rights people wanted to continue pushing their cause, the IRA wanted to show support, Faulkner wanted to get tough with Catholic militants, and the Parachutists wanted to use their well-rehearsed war-winning plan – they had proposed using it against a previous demonstration but permission was withheld.

From this point, the story is well documented by ample eye-witnesses. The marchers came down William Street just before 4 p.m. and came to a halt at a barbed-wire barricade near Waterloo Road. At the head of the march came forty to fifty youths tossing stones and shouting abuse, as is usual in Londonderry riots.

Equally accustomed to this, and running very little risk from stone-throwers because of their protective anti-riot gear, were the soldiers on the barricade and around the walls. Most of them had been in Londonderry a long time: the 1st Royal Anglians, 2nd Royal Greenjackets, 22nd Light Air Defence Regiment and the 1st Coldstreams.

None of the organisers of the march had ever thought it would go any further than this point. ‘We thought we’d get some rubber bullets and a bit of gas and then we could go to a meeting with the feeling that we had fought for our beliefs,’ one of them told us. ‘There was some abuse and stone-throwing, as there always is, but the RUC have taken ten times as much provocation without opening fire as the British Army did last Sunday.’

At this point the demonstrators had no reason to suspect that the Army reaction was going to be in any way out of the ordinary. They could see the Army snipers posted on the walls of Derry, which look down menacingly on the Bogside, but this was quite normal. They could also see the Saracen armoured personnel carriers parked on the other side of the Army barbed-wire barricade, which prevented the demonstration going any further down William Street towards the traditional objective of Guildhall Square. Indeed, the march organisers sent two young girls through the barricade to count the parked Saracens and return with a report.

Observant demonstrators did see something unusual: on the boundary walls of the Presbyterian church in Great James Street, on the roof of the GPO sorting office in Little James Street, and in the ruins of Richardson’s Factory (burned out in 1970) they noticed Paratroopers, easily recognised by their distinctive red berets, stationed with FN rifles. This, unknown to the demonstrators, was a part of Colonel Wilford’s mass IRA lift operation; the Paratroopers belonged to the 1st Battalion of the Paratroop Regiment.

These soldiers had arrived by Army trucks in Derry that morning; the battalion had never been in Derry before. They had come from Hollywood Barracks near Belfast and were to return, the operation completed, that same evening.

A water cannon came up and sprayed dyed water across the barricade onto the marchers. Some rubber bullets were fired, followed by CS gas. Word immediately went down the mass of the march – at this point the procession was backed up for more than a mile – ‘Back to Free Derry Corner for a meeting.’

A demonstrator, Seamus Morrison, 44, unemployed barber, describes the first ‘real’ bullet to be fired:

After the instruction from the march organisers to assemble at Free Derry Corner for a platform meeting, we moved across a vacant lot in William Street. A few stones were thrown at the Paras on the church and on the post office but nothing excessive. Suddenly there was a report, quite different from a rubber bullet going off, and a young boy screamed: ‘I’m shot, I’m shot.’

This was Damien Donaghy, 15, who fell near the Grandstand Bar in William Street. A high-velocity bullet had fractured his femur (the thigh bone) according to Dr Raymond McLean, a Catholic doctor and demonstrator who was later asked to examine the dead and wounded by Cardinal Conway, Catholic Primate of Ireland. In the event Dr McLean was present at most of the examinations and got a good view of the wounds.

Donaghy was in no sense a leader of the march, and was hit well back from the march leaders. He was in no way remarkable, except that he was dressed in blue jeans and a Campari waterproof jacket – not an unusual dress in Northern Ireland but, combined with his youth, just possibly what an Army briefer might describe as the likely appearance of an IRA man. We are confident that in fact he was certainly not.

One Official IRA man was, however, nearby in a burned-out building opposite Richardson’s factory. He had been posted there as an observer, and was armed with a .38 pistol – although his orders were that he was to be unarmed. After Damien Donaghy was shot he says he fired a single round at the soldiers on the sorting office (GPO) roof. We make the range fifty yards – an impossible range for accurate shooting with a pistol. This is the only Official IRA shot we can trace during the afternoon. As Donaghy lay on the ground, a stranger to him, John Johnson, 57, manager of a drapery shop in the Strand, the main shopping centre of Londonderry, ran to his assistance.

The spirit of mutual help is strong in the Bogside; Johnson was one of a score or more of demonstrators who ran towards the wounded boy. Another shot rang out and Johnson was hit in the leg. Seconds later there was another shot and Johnson was hit in the shoulder by what Dr McLean says was a ricochet. We have no doubt that the Army fired both these rounds.

The two wounded demonstrators were carried by people near them to nearby houses, again an automatic reaction in the Bogside. But stone-throwing, shouting and the firing of rubber bullets continued, and not more than a hundred demonstrators in the immediate vicinity were aware that people had been shot. (There were, by this time, several thousand people in Lower William Street.) However, many demonstrators have told us that from about this time they began to feel that something was going very wrong, that the Army reactions were very different from those shown in a ‘normal’ Derry riot.

No more shots were fired for between ten and fifteen minutes. This was the period when, according to the Army plan, fire should have been returned by the IRA, or they should have been seen running home for their weapons.

However, no engagement developed and demonstrators, still not unduly alarmed, continued to press through Rossville Street, Chamberlain Street, and across the nearby empty sites towards Free Derry Corner, where traditionally they would be safe and the riot would have run its normal course. At this point the demonstration was no longer a march and was transforming itself into a crowd going towards the forthcoming meeting. All movement towards Guildhall Square had ceased, and there was no further pressure on the Army barrier in William Street, except for sporadic stone-throwing. At this point another shot rang out and Jack Duddy, 17, a weaver in a Derry textile mill, fell dying in Chamberlain Street. A Catholic priest ran to him and as Duddy’s body was carried away walked in front waving a blood-stained white handkerchief.

Almost simultaneously Mrs Peggy Deery, 37, mother of 15 children, was hit in the back of the thigh by a high-velocity bullet which almost severed her leg (the Italian photographer Fulvio Grimaldi witnessed Mrs Deery being hit). She was carried into a house at the top of Chamberlain Street and is now in a serious condition in Belfast Hospital.

Almost immediately the serious Army operation began. Soldiers lifted the central section of the knife-rest barbed-wire barrier in William Street, opening a path for movement towards the demonstrators.

From Little James Street, running into William Street, seven Saracens led by a Ferret scout car emerged and raced up Rossville Street, at a speed which a trained military observer, ex-Sergeant-Major James Chapman, puts at 40 mph. All witnesses agree that the Saracens which frequently appear at Ulster demonstrations have never been driven at this speed before.

Within the next few minutes a dozen more people were shot down and many wounded. Civilian witnesses describe a scene of horror in which the Saracens pulled up, apparently at random, soldiers jumped out and began shooting, apparently indiscriminately, at the panic-stricken crowd running frantically for their lives. Ex-Sergeant-Major Chapman describes exactly the same scene in terms equally shocked and horrified but clearly disclosing the military plan, such as it was, behind this exercise.

The Saracens took up rehearsed blocking positions along Rossville Street and next to Rossville Flats. Paratroopers wearing combat and not anti-riot gear jumped out and dropped into standard British Army firing positions in spots clearly selected in advance for the purpose of the operation.

This clearly was to ambush the supposed concentration of IRA men in the Harvey Street/High Street/Eden Street/Chamberlain Street area, pinning them against the Army defences in Waterloo Road. This area is usually a battleground between the Army and the stone-throwing demonstrators in ‘normal’ Derry riots. Another platoon ran through the narrow alleys and walkways of the Little Diamond area, also a traditional battleground.

Executing the normal fire-and-movement tactic taught to British infantry (the trained and the untrained witnesses agree exactly on this, using different terms) the Paratroopers cleared the barricades in Rossville Street by shooting everyone on it or near it. Kelly, William Nash, Young and McDaid were killed here – ex-Sergeant-Major Chapman saw three people hit and slump on the barrier. Everyone at the barrier, considered by Bogside people to be their main line of defence, was either dead or wounded. Nash senior raised his arm to try and stop the shooting, was hit in the arm and lay shouting for an ambulance. A section of Paratroopers running through the Little Diamond to link up with their comrades at the barricade got behind it – there was no one left alive to stop them – and began laying down a field of fire behind Rossville Street flats. In this shooting Gilmore was killed; McGuigan who ran up to him was killed, and Doherty, crawling along at some distance to escape, was shot dead in the same line of fire.

Paratroopers leading the Little Diamond pincer movement ran into Glenfada courtyard, where a handful of demonstrators had taken refuge, and began shooting – a normal street-fighting tactic when entering a possible ambush area; in this shooting Wray was killed and Friel wounded. This section continued through to Abbey Park and repeated the clearing fire, killing Gerald Donaghy, Gerald McKinney and William McKinney. The three bodies were piled up on top of a short flight of steps in Abbey Park. People under fire ran out from nearby houses and dragged the bodies in and Dr McLean, who was present, at once pronounced them dead.

Meanwhile the attempted encirclement of the Rossville Flats/Chamberlain Street was continuing. A Saracen raced into Rossville Flats parking area, the crew realised that they were not in the spot allocated by the operational plan, and the driver reversed the vehicle against a low retaining wall (crushing Alana Burke) and raced out to its allotted position. McElhinney was shot dead about this instant in the centre of the same parking lot; we have not been able to find an eye-witness to his death but medical evidence is that a high-velocity bullet entered his left buttock an inch from the anus and carried the length of the body and exited at the right side of the shoulder – a wound only possible if he was shot on hands and knees while crawling.

As McElhinney fell, Michael Bridge, a Civil Rights steward wearing a white armband, ran up to him, saw he was dead and, overcome with rage, turned towards the Saracen standing at the entrance of the parking lot, raised his arms and shouted: ‘You murdering bastards.’ A soldier standing next to the Saracen, he says, shot him in the thigh. We have studied a photograph of this incident taken by an amateur photographer; Bridges can be clearly seen with his arms outstretched in the attitude of someone shouting abuse. His hands are visible and they are empty.

Meanwhile the Paras were blocking the entrance to Chamberlain Street. A young French photographer, Gilles Peress, who works for the famous Magnum photo agency, was running up Chamberlain Street behind fleeing demonstrators when, as he passed Eden Street, he saw a Paratrooper kneeling by a burned-out car. He raised his camera over his head and shouted: ‘Press!’ The soldier fired a single round at him. We have paced out this incident described by Peress and discovered a bullet-hole in the front of the house on the corner of Harvey Street and Chamberlain Street, which confirms his story and indicates the bullet went a few inches wide of his head.

Seconds later, Paratroopers burst into a house at the end of Chamberlain Street – the same house to which Mrs Deery had been carried.

They were asked into the house by a woman who ran out shouting: ‘Get an ambulance.’ Inside the house they arrested 22 men, demonstrators who had taken shelter, and marched them down Chamberlain Street – a part of the mass round-up of ‘IRA militants’ which lay behind the whole operational plan. All these men have since been released.

After the shooting stopped, the Paratroopers began loading the dead, dying and wounded into the Saracens; lining up demonstrators against walls and searching them; and leading arrested groups away at gunpoint, accompanied by, in some cases, blows from gun-butts and batons. These activities were all overlooked by Rossville Flats, where IRA snipers, had there been any, would have had easy targets. No eye-witness reports any shooting at the soldiers at this stage. (One soldier was admitted to Altnagelvin Hospital after the Sunday shootings. The hospital management have been instructed by the Army not to disclose either the regiment to which the soldier belonged or the nature of his injury.)

The IRA did, however, enter the picture after the Army shooting ceased. IRA men on the march included the head of the Bogside Provisional organisation, who was seen by a number of witnesses early on the march. The IRA Provisional group had a hasty conference when the shooting began and, according to a young woman who was present, decided to do nothing. The Official group at the march, however, sent an urgent call for gunmen, and one ‘active service unit’ arrived some minutes after the last Army shots were fired. This consisted, like all IRA active service units, of four men armed with two .38 pistols, a .303 Army rifle and a .22 hunting rifle with a telescopic sight.

One of these men fired one pistol shot at long range towards the Army, but does not claim he hit any soldiers. This shot was the last one fired in the engagement and we believe the only one fired at the Army – we can find no witnesses, among dozens, who heard or saw any other. Every Catholic present at the demonstration to whom we talked, and they include priests and doctors, supporters of both wings of the IRA, and people opposed in varying degrees of vehemence to the IRA, are unanimous that the IRA played no part whatever in provoking the Army operation or fighting back, other than the shot mentioned above. In the atmosphere of grief, shock and horror which has followed the shooting, it is inconceivable that the tightly-knit Bogside community would not lay at least some of the blame on the IRA, if in this case they deserved any.

We have no choice [but] to conclude that this was a Parachute Regiment special operation that went disastrously wrong.

WOUNDED

1. Joseph Friel, 20, tax officer: ‘Five soldiers ran around a corner at Rossville Flats firing from the hip. I was hit in the chest by one of three shots I heard fired. I was just standing, I thought I was safe. An Army doctor put a wound dressing on me. I was never searched. I don’t know why they shot me.’

2. Patrick Campbell, 53, docker: ‘I was running away from the Saracens when I was hit in the back. I never saw who hit me – I suppose it was the soldiers because they were running after me. No one else was firing.’

3. Alex Nash, 52, unemployed painter: ‘I saw my son Willie (19) shot down with two other lads at the Rossville Street barricade. I knew he was dead but I ran forward and raised my arm to stop the soldiers shooting any more. They shot me in the arm. I fell down and they fired at least six more rounds at me. I thought: “Oh Christ, if I get up they’ll shoot me again.”’

4. Michael Bridge, 25, unemployed labourer: ‘I was a Civil Rights steward at the meeting, so I had on a white armband. I tried to get the crowd back from the barricade – young lads throwing stones – when I was hit in the foot with a rubber bullet. I ran away as fast as I could and nearly fell over a young boy lying dead. I lost my head and ran towards the Saracen shouting, “You murdering bastards,” and waving my arms. A soldier standing next to the Saracen shot me in the thigh. I ran a few steps on my nerves and fell down.’

5. Michael Bradley, 22, house painter: ‘I was throwing stones at the soldiers – my blood was up, you know. I had just finished throwing a stone when I saw a soldier aiming at me from about twenty yards away and I was hit in the arm and in the chest. I just caught a glimpse of him – he was to one side of me and I didn’t throw the stone at him, at a Saracen.’

6. Paddy O’Donnell, 40, foreman asphalt spreader: ‘I heard shooting and tried to push an old woman down to the ground when I was hit from behind in the shoulder. Soldiers came running and shouting: “Put your hands up.” I said I was hit and they said: “Come on, get it up, or you’ll get it up.” I called to a priest and tried to speak to him and a soldier hit me with his baton.’ (O’Donnell has a stitched wound six inches long in his scalp.)

7. Patrick McDaid, 24, plumber: ‘I saw a Saracen coming and ran in front of Rossville Flats. They were shooting everybody. I felt a pain in my shoulder and a man told me I was hit. I had just sort of pulled my head down or I think I would have been killed.’

8. Alana Burke, 18: ‘I went with my girlfriend to the march. I went up to count the Saracens and the soldiers took my photograph; they always do at the marches. Then they started to use the water cannon with dye and I thought I caught the lot – there was some sort of gas in it too. I was running away when the Saracen suddenly came at me and pinned me against the wall. I managed to crawl down a laneway and get away.’

Gilles Peress, 25, has been working with the Magnum international news agency in Northern Ireland since 1970. He arrived in Londonderry the day before the Civil Rights march, which ended in the Bogside, was due to take place, after covering the Dungannon to Coalisland march for his agency. Peress went with the head of the march, taking photographs of youths who were stoning soldiers at the William Street barricade and tearing sheets of corrugated iron from shopfronts to make shields against rubber bullets. ‘I have photographed many riots like this before,’ he says.

Suddenly I saw the Saracens come out of Little James Street. They were going very fast. I thought they were charging the crowd to frighten them.

The people ran up towards Rossville Flats. I ran behind them up Chamberlain Street, stopping every few yards or dropping into a walk to take photographs. One of the crowd, a young man wearing a false beard and moustache – a common practice of people who do not want to be photographed by the Army – beckoned me to run over to Eden Street, saying: ‘There’s a soldier there.’

I held my camera over my head, passing the corner I saw a soldier, wearing a parachutist’s helmet, kneeling against the wall with a rifle aimed at the crossing. I shouted ‘Press’ and waved my cameras. Then I walked slowly on. The soldier fired a single shot at me. I have subsequently seen the bullet hole and it shows that the bullet passed a few centimetres from my head. I do not say that the soldier was trying to kill me, but I do say that he took the risk of killing me.

I continued running up Chamberlain Street and I saw a priest waving a blood-stained handkerchief as he stood next to a body lying on the ground [Duddy]. I photographed this scene. In the parking lot outside Rossville Flats I saw two soldiers kneeling and firing slowly and methodically. It seemed as if they were carrying out a drill.

Unable to photograph there I went through the passage under Rossville Flats and on the other side I saw a dead or dying man and another crawling towards him to help him. I photographed that scene, and also a young man trying to hide flat out on the ground behind a tree. Going along the wall of the flats I saw and photographed a man shot in the eye and a young man shot in the stomach. The shooting stopped about this time and I continued to photograph the arrests and the taking away of the dead and wounded by the soldiers.

At no time did I see a civilian carry a weapon, fire a shot or throw a nail bomb. I saw no weapons or bombs abandoned on the ground. I heard two shots fired from somewhere near Free Derry Corner at the end of the action. There were no soldiers at that point, and they sounded like pistol shots. Otherwise all the shooting I saw was done by the soldiers.

Thomson House, London

Date: 19 Feb. 1972

From: M. Sayle

To: H. Evans and others interested

I don’t want to seem paranoid about this, but I don’t think this should leave the ‘Sunday Times’ office.

BLOODY SUNDAY.

I feel I should set down the very great difficulties which, as I see it, we face over this matter.

A note as to working methods might be a helpful beginning. I shall be extremely pleased if someone else from the paper, or better a group, go over all this again from the primary sources (eye-witnesses, photos taken on the day, the bullet marks and other evidence still visible on the ground, and above all the ground itself) testing what I have to say in the most critical fashion. I am convinced that this reworking of the material will bring the new group in a week or so to where I and the people who were with me are now, and I am writing this memo on that assumption.

My own working methods were these. Getting there the day after the incident it seemed to me that we had to clear up these points before we could go any further: was there a military plan behind this, or was it a riot by the Army or a breakdown of discipline? If the latter, how did it happen that discipline cracked in one of the most skilful and professional outfits in the world? If the former, what was the plan, and was it carried out?

At this point a search for witnesses began. The most obvious place to start was the wounded in Altnagelvin Hospital. At this point I suggested that an artist should come over, and John Butterworth arrived and quickly and competently drew up our map – which incidentally is being used by Widgery and his team.

Next step was to plot where the wounded were hit, both in the sense of their injuries (which I looked at) and where they were on the ground when they received them, indicated by getting them to mark the map. We then added the positions of the bodies, as far as we could by examining photographs taken at the time, and by getting eye-witnesses to mark our chart.

This procedure seemed to have one tremendous advantage: we were asking people, not to interpret what they saw, but to give specific information. As we did not ourselves know what this chart might reveal it seemed (and seems) impossible that all these different sources could have been conspiring to feed us wrong, but still consistent information – which all had to square with our photographs (and the medical evidence).

The chart, when ready, told and tells a great deal. Two lines of dead and wounded intersect (and on the ground even more neatly than they do on the chart) at a spot I call ‘key point’. Another group is scattered in the carpark in front of the flats, and two other wounded – Donaghy and Johnson, hit by eye-witness accounts ten to fifteen minutes before the main shooting started – are separated in both time and space.

We then added the movements of the Paras, as described by eye-witnesses, and checked against still photographs (this needs to be done against the television films).

Strong suppositions began at this point to emerge. The Army version that some sort of gun battle with the IRA took place (denied by all the eye-witnesses so far spoken to, priests, Bogsiders and journalists) became even less probable, unless the idea that the IRA advance in lines can be admitted. A clear military plan can easily be seen, an ambush operation which I have indicated by additions to the map. A walk around the ground (I have now made ten) reduced the situation to two possibilities: either this was the plan that was being attempted, or we have discovered the possibility of a neat military operation, very typically parachutist, which the military themselves missed.

My own work since has been in two directions: sifting eyewitness accounts to see if they fitted the scenario – not, let me stress, asking them if they agreed with me, but asking apparently aimless questions – and working on military sources for confirmation.

On the first line of attack, I have now studied more than two hundred different accounts, either in person (eight wounded, six priests, ten journalists and about a score of Catholic Bogsiders present) and the rest the written statements collected by the Civil Rights people and handed over to the London Civil Liberties team headed by Tony Smythe. I have not so far found any discrepancies of weight, and an enormous number of details which, while not proof, each add their little bit of persuasion to a structure which I submit is now overwhelming.

So I am satisfied there was a plan, and that in broad detail it is indicated on the chart. There is an account of it in the story filed by myself and Derek Humphry from Derry on 3 February, but for the benefit of new readers I will recap. Briefly, we say this was an attempted mass lift by A Company of the 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment. The idea was that a CRA march was to be allowed down William Street as far as the barricade opposite the burned-out cinema, where ‘normal aggro’ was expected, and did in fact develop. Some shots were then fired; the Army expectation, normally quite sound, was that those who stayed to give more aggro after this would, if rounded up, be found to contain IRA men or at least men of IRA timbre, people who, if not in the movement, could be expected to join it.

The ambush was therefore ordered in – we see the three APCs which charged from Little James Street down Rossville Street, the seizure of the ‘key point’ involving clearing the barricade just in front of it and the courtyard behind it going towards Glenfada Park. (‘Clear’ in less military terms would mean ‘shoot those on it or near it.’) The barricade and the courtyard both offered risks to the Paras (four men by all the eye-witness accounts) at the ‘key point’, the barricade because it offered cover to any hypothetical IRA men who were about, who could have got behind it and thrown nail bombs or opened up with Thompsons, the courtyard because the four Paras could be shot from behind by anyone in the courtyard.

The remaining line of bodies are on the line I call ‘line of fire closing box’. The presumption that they were shot because they were running out of a box (all unknown to them, of course) makes all too much sense. The Army statement afterwards that all those shot were males of military age fits in neatly here – the statement is roughly true; even the woman shot was wearing slacks and a vaguely khaki jacket, according to eye-witnesses, and the clothing of both dead and wounded fits very roughly into the classification, ‘male of military age wearing a combat-type jacket’ – both the statement and the dress of the casualties pointing to an operational restriction on shooting anyone not male, of military age and wearing a combat-type jacket.

The planned lift did, in fact, take place; but we also have the gravest doubts that any substantial haul of IRA men was made. Only one man has been interned after this lift, the wounded were not searched or questioned and there is no military guard over them. Of the 13 dead, 12 either had jobs in Derry outside the Bogside or were at school – and so could have been lifted any time without the need for a mass lift. Who then are the four wanted IRA men stated by the Army to have been among the dead?

I will not begin in this memo to list the endless fitting together of bits that has gone into this. A couple of examples. I studied the statement of the Scottish Chief Constable that he had heard automatic fire and, as the Army had only self-loading rifles, automatic fire must have been opened by the IRA. Sound, and a serious difficulty – until I found on one of Peress’s pictures a shot of a Para in jump helmet carrying a Sterling slung over his shoulder. End of Scottish copper’s theory.

I will write, or supply to anyone who is interested, the stuff from eye-witness statements and the photographs on which all this rests – it is far more solid than, understandably perhaps, people in London realised. My purpose is not, however, to vindicate my judgment – I am confident a reworking of the evidence will do that – but to point out the minefield we now face.

Clearly the Paras have been unlucky – the absence of the IRA, who decided that the Paras were in Derry to do a mass search of Creggan while the people were away at the march, was an element they could hardly be blamed for not knowing about, and under normal circumstances some sort of gun battle or at least fire from the Rossville Flats could confidently be relied on under the circumstance of Bloody Sunday, and we would have written a very different story about the events – ‘IRA men brought to battle by Paras, some civilians hit in crossfire, rough tactics but effective in the circumstances’.

However, given that the Paras were putting a plan into action, either as described or very like it, we have to consider its legality in terms of the yellow-card rules (which are the legal basis of the Army firing at anyone in Northern Ireland). Broadly, the card allows soldiers to fire at people either because of who they are (known IRA men, but the Paras had never been in Derry before, and no eye-witness speaks of them consulting photographs) or because of what they are doing – holding bombs or guns, making threatening movements, reaching for weapons etc. What the card does not allow is for people to be shot because of where they are, which seems to have happened here. Indeed, I don’t see how battle tactics of the type described could even be applied to IRA men supposed to be hiding among a crowd of sympathisers without violating the yellow-card rules.

Let us draw the full conclusions from this. The plan itself seems to have been illegal under the circumstances. There is no way, therefore, in which at least some of the blame can be kept from the people or person who authorised it. Was he honestly told that it carried a high risk of ‘civilian’ (i.e. Bogside sympathisers with the IRA) casualties? If not, the people who submitted the plan are guilty of, at least, manslaughter; if so, the people who authorised it are. We cannot get to the bottom of this without looking into the command structure of the whole Army operation in Northern Ireland, with, let us make no mistake, a strong possibility that when we find out how the command set-up works and who authorised these operations, criminal charges may be appropriate.

Our Widgery/book strategy3 therefore needs to be carefully thought out. If Widgery develops into an oath-against-oath confrontation restricted to what appeared to various people to happen about the time of the shootings, only confusion will result. If we attempt to clarify it we may find ourselves trying to press manslaughter charges against colonels, generals or civilian politicians in Northern Ireland, Faulkner among them because of his membership of the Security Committee, when the same men have in effect just been cleared (or at least, pronounced ‘not enough evidence against them’) by the Lord Chief Justice of England.

On the other hand we have a position to maintain in Ulster coverage, and there is nothing to stop rival papers going on with the story.

Book-wise, it seems, to oversimplify a bit, that either Widgery writes the book for us, or we are left with an account which no lawyer will let us publish. The expense of re-Widgerying Widgery, or indeed of going much further than we have already, is also going to be heavy.

But, equally, we clearly cannot let the matter drop. I can only advise that we keep book options open by avoiding any commitment to do what may well prove impossible, and keep some sort of inquiry of our own ticking over – but we have more or less completed what we can learn from Bogsiders, journalists, photos and the ground, and now the trail leads to the Army and Northern Ireland command structure.

On military confirmation I have two things to report.

I checked over the map with a Captain of the Light Anti-Aircraft Defence Regiment I chatted up for two hours on a very rainy street corner. He agreed I had got the plan right, agreed that it was a very pretty one if used to capture Rommel’s headquarters or a Rhine bridgehead but inappropriate to use against a demonstration, then added: ‘But the Army can’t admit we were in the wrong, can we?’ I deliberately did not ask his name, as no doubt he has reported our conversation to Army Intelligence like a good soldier, and I did not want to scare him off in case of possible future use.

Last Monday night (14 February) I was invited down to Drummenhoe Barracks, just outside Derry, for drinks with Captain 028,4 PRO of the 41st Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment (they have been in Derry for two months). The contact was through a local journalist, a very naive Protestant, who said the Army wanted to talk to me.

028 shot me an incredible line. He said he had been present at the demonstration himself, dressed in plain clothes and a wig, and had seen the IRA open up with Thompsons near the barricade site, thus killing their own people. One body, he said, had a .303 bullet in it, proving that the IRA had shot because they have .303s stolen from British Army barracks. So, I pointed out, have the marksmen on the sniper posts around the Bogside. He produced a boy of 14 who said he was from the Bogside and said he had seen the IRA men open up with Thompsons and nail bombs. I asked the boy was he sure about the nail bombs; he said yes. Ten minutes before 028 had said he had heard no nail bombs and not one witness heard any nail bombs. I suspect this boy is lying, either for money or because he is in some way related to one of the numerous Bogsiders serving in the British Army. What, I asked 028, is this boy doing alone in a British Army barracks near midnight? 028 then asked me if I would drive the boy home myself, only later changing his mind about this.

028 then launched on a wild rambling tour d’horizon. The Army had to win in Ulster, he said, otherwise violence would submerge Europe. A lot of them were Communists, he told me. All Catholics were liars ‘and the gentlemen of the cloth – well, you know about them, old boy.’ Then, on another tack: ‘You know, old boy, I often think that one of our marksmen could knock off Bernadette, John Hume and the rest of them – that would end the whole thing in a matter of days. Worth thinking about, eh?’ Then, getting deeper and deeper into the whiskey: ‘You know, old boy, there’s only one thing we really want here. We just can’t let people at home think we shot unarmed men in the back. We just can’t have people thinking that, can we?’ Then about the 14-year-old boy: ‘It was his conscience, you know. He lives in the Bogside himself, but he just had to tell us that the Army were not to blame – he just couldn’t see us slandered by those IRA scum like that.’

028 then showed me the model the regiment have made of Derry – they made it in Germany, it’s about the size of a billiard table, very detailed. He said he had volunteered to give evidence and added that the Army marksmen on the walls watched everything through binoculars and were going to give evidence that they saw the IRA open up with Thompsons etc.

I am sure this man is lying, no doubt out of some mistaken view that the Army need to protect their good name. I relate the incident partly to let our people know what we might expect to hear at Widgery, also with a note of caution: I don’t want to be over-dramatic, but I think that any army caught in this sort of embarrassing bind, and with officers’ reputations and careers at stake, is capable of playing it very dirty indeed. The same, of course, goes for the IRA, and I advise the utmost caution on everyone, and full disclosures among ourselves, or we could be sold some very alarming bills of goods. As the 028 confrontation indicates, attempts will certainly be made in this direction.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.