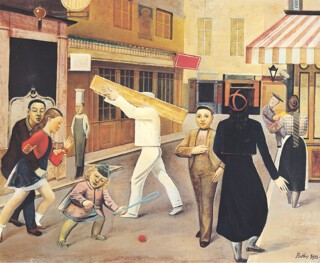

Balthus first attracted notice early in 1934 with a small exhibition at the Galerie Pierre in Paris. Several of the works he showed – The Street, The Window and Alice – seem as startling now as they must have done then. This Catalogue raisonné, published not long before the artist’s death earlier this year, enables us to determine the unremarkable ingredients that so surprisingly and so explosively combined to make these paintings possible.

In 1926, at the age of 18, Balthus travelled to Italy and made copies of pictures by Masaccio and Piero della Francesca. Despite the impression given by most writers on the artist, this was not an extraordinary thing to do. Indeed, Balthus’s father, also a painter, and his mother, the muse of Rilke, were both enthusiastic admirers of Piero. Furthermore, Balthus had been urged to emulate the Italian primitives by the French Symbolist and defender of Classicism, Maurice Denis. On his return from Italy he painted murals of the Good Shepherd and the Four Evangelists in a Swiss church. In the winter of 1927 he turned his attention to the streets and quais of Paris, perhaps inspired by the gritty canvases of Maurice Utrillo, who was then at the height of his reputation. Then, in 1932, after completing French military service, Balthus made some copies after Jacob Reinhardt’s late 18th-century paintings of Swiss peasant couples in traditional costumes, exaggerating the doll-like quality of the originals: these are the earliest examples of the faux naive manner to which he was attracted throughout his life.

Having moved into a large Paris studio in 1932, Balthus realised that he had the room to enlarge a view of the city that he had painted several years earlier, and to make it as disciplined, indeed as monumental, as a composition by Masaccio or Piero. The edges of forms in The Street were sharpened and the receding lines of pavement, shop windows and striped awnings emphasised, making the picture more artificial, more stagey. Other strong diagonals, notably a builder’s plank, are placed parallel with the picture plane, creating a tension with the receding lines. The colours in the background are matched with those in the foreground, so there is no aerial equivalent to the linear perspective. On this taut, busy set, pedestrians move with puppet-like stiffness. Only one figure relates to, or rather collides with, another: the young man in black who assaults the schoolgirl in white ankle-socks (his gesture was made less obviously indecent by the artist at the request of the owner, James Thrall Soby).

Balthus had long had a talent for illustration and he now developed an interest in stage design. In 1933 he started drawing episodes from Les Hauts de Hurlenvent (as Emily Brontë’s novel is known in French) and the following year he designed sets for Shakespeare’s Comme il vous plaira. His work helped reintroduce linear perspective and some kind of narrative content into avant-garde Parisian painting, and in the best of his pictures of this time perspective can even be said to become part of the narrative. In The Window a young woman, perched on a window seat, stares in terror at someone – at us – entering the room, that is, looking into the picture. The lines of the windows which open on either side of the woman seem to converge on her, and the diagonals of the roofscape behind radiate from the rigid lines of her face and body with a pattern like shattered glass. In this case the Peruvian model was repainted to look less exotic but more erotic (one breast now emerges from her blouse). The Catalogue raisonné shows the original and final appearances of both this painting and The Street.

Nicholas Fox Weber, who does much to reconstruct the intellectual circles in which Balthus moved at this date, offers a psychoanalytic interpretation of The Window. Balthus here ‘empowered himself to push his mother through the very sort of opening’ that had been an obsession for both her and Rilke. Painting itself is – or certainly had been before 1900 – a window. Or a mirror. These metaphors, when revived in 1933 by an artist whose friends were fascinated by Freud, were disturbing. You can break in by or fall through a window; a mirror or the reflecting glass of a window is somewhere you might meet a double, or the truth, or a voyeur, or your doom. Magritte and Delvaux made paintings of mirrors and windows in these same years and it would be valuable to see them reproduced in a study of Balthus’s work.

Alice shows a woman precariously posed with one foot raised on a chair, carefully combing her hair, careless of a breast that has escaped from her shift and of her genital area visible below it. For Sabine Rewald, writing in the excellent catalogue of the 1984 exhibition in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, this picture radiates a ‘suggestive, sensual warmth’, while Nicholas Fox Weber in his biography describes the woman as a ‘jaded, worn-out tart’ whose powerful legs recall the ‘pincers on a prehistoric reptile’. Rewald exaggerates the sweetness of the sandy palette (‘tones of amber and honey’) but she acknowledges the fact that the woman does not respond to us. We are seeing her looking at herself – Alice through the looking glass. The Catalogue raisonné informs us that this was certainly the artist’s intention. Reflection often prompts reverie. Hence the cloudy eyes. We are violating her privacy.

Fox Weber believes that the title Alice must have had an ironic purpose – how else could Balthus give his ‘snarling hussy’ the name of the ‘most beguiling and innocent of little girls’? But Lewis Carroll’s heroine is not especially beguiling or innocent, or indeed little (except briefly), and her reactions to the crazy world in which she finds herself are briskly commonsensical. It must have been the deadpan prose of the books which appealed to the Surrealists and this quality has an equivalent in the flat colours, plain lighting and direct handling of Balthus’s pictures of the 1930s.

Two other paintings, The Guitar Lesson and Cathy Dressing, also exhibited in the 1934 show, now enjoy considerable celebrity but seem to me less powerful images, although they were more blatantly shocking at the time. The narrative in these paintings is more explicit but it is invented – unlike the other three paintings, all of which develop from something the artist had seen. They cleverly borrow the clumsy style of 19th-century magazine illustration, of the kind used by the Surrealists in their collages. This is what makes the scene of the music teacher masturbating her pupil seem somewhat quaint. Balthus appears to have responded best to a model – or to a sitter. In the 1930s he painted a dozen striking portraits, including the Vicomtesse de Noailles, Joan Miró, André Derain, Pierre Renoir, the Blanchard children . . .

His famous landscape of 1937, Summertime, or The Mountain, a view of Beatenberg above Lake Thun in Switzerland, where he had often stayed and where his murals had been painted, has portraits within it. Balthus himself is the male hiker who rests on one knee in an attitude of resolve or triumph while one female companion (his future wife) stands and stretches and the other (an English friend) sleeps. It has been observed that the picture has something of the clumsy ruggedness of Courbet. It also has something of the eerie, sunlit stillness of Salvador Dalí’s landscapes of those years, and they may have prompted the anthropomorphic rocks that mimic the poses of the figures. ‘Je fais du surréalisme à la Courbet’ is a phrase that has been repeatedly attributed to Balthus.

He later denied saying this and also did his best to minimise or deny his many contacts with Surrealism. ‘Peindre est une prière. L’acte de peindre lui-même est prière. Mais il faut aussi prier avant de peindre,’ the elderly artist intoned in an interview. This doesn’t apply to his paintings of the 1930s, except perhaps to his other major landscape, Larchant of 1939, an exercise in restrained pictorial geometry designed to give eloquence to the church tower set in the middle distance but just breaking through the horizon – the tower of an ancient church, made a symbol of la France profonde, as invoked in the poetry of Balthus’s friend Pierre-Jean Jouve.

As France surrendered to Germany, Balthus (of Polish extraction, born a German citizen, frequently a Swiss resident, but when he died a French national) began to associate his art with Cézanne, by then generally agreed to be the most French and the most rural of geniuses. In 1940 he constructed a solid self-portrait from blocky patches of earthy colours. He also adopted Cézanne’s two great subjects: fruit on a simple table with cloth in mountainous profile behind, and trees with branches that lock into the pattern of distant fields and rocky slopes. Throughout his life Balthus would return to this type of still life and landscape, often in a lighter and brighter palette.

In his most memorable paintings the compositions are more resolved than Cézanne’s with their endless optical checks and pictorial balances. The monumental Golden Days of 1944-46 is a good example. The canvas is divided from top left to bottom right by the diagonal of a girl outstretched on a chair. The line of her raised left leg is paralleled by the opening of the hearth behind her and the raised arm of a man kneeling to feed the fire. The straight lines are contrasted with carefully varied and spaced curves – a bowl by the window, the back of the chair, the edge of the girl’s hand mirror, the face of the clock on the mantelpiece. The prominent nude in an angular pose, the diagonal and largely planar composition, the rudimentary furniture – all these elements recur in the work of future decades.

In Golden Days light – from the fire as well as the window – is as much the subject as adolescence. Balthus’s interest in light was inseparable from his interest in texture – texture which sometimes comes from only lightly covered canvas weave, or from dry, dragged paint, or from knifed impasto. By the time he painted Golden Days he had become a painter of the beautiful and the mysterious. But during the 1940s and 1950s heavy paint is used to define solid things. By the 1970s the use of texture indicates, as it does in the pale, parched paintings of Puvis de Chavannes a century before, that a higher world is being revealed. Instead of being effortful or emphatic, the use of outline can seem a tentative attempt at definition of something ineffable. Balthus left prosaic, factual and forceful painting behind, and it is noteworthy that his few attempts at portraiture after 1940 are relatively feeble.

The artist’s assumption of a title (Count Klossowski de Rola), his grand dilapidated château in the mountains of Morvan in Burgundy, then his move to the Villa Medici as Director of the French Academy in Rome, and the photographs taken by Cartier Bresson (and approved by Balthus) which depict him as an elderly endangered raptor, have helped reinforce the idea that he was a living Old Master with privileged access to classical ideals and traditional practices. In fact, though, there is little evidence that he drew inspiration from museum art.

Balthus seldom looked back at his early masterpieces, but between 1952 and 1954 he again painted a Paris street scene, Passage du Commerce Saint-André. The figures are smaller than in The Street, and are either still and pensive or slow and deliberate in movement. The simplified shapes of the figures (several in profile, others repeated, one seen from behind) and the carefully calculated intervals have the odd neo-Egyptian solemnity – and near comedy – of Seurat’s scenes of suburban recreation.

The quiet palette and meditative atmosphere of much of his late work has suggested parallels with Morandi, whose paintings Balthus is known to have admired. But Morandi handled oil paint with a confidence and a feeling for its creamy consistency never found in Balthus, and the bottles that were his chosen subject offer no hint of narrative or symbolism, whereas Balthus invites us to ponder what it is that his adolescents are absorbed by, what it is they see in their mirrors or books or dreams and in the radiance which bathes them. What it is, the artist himself surely did not know, any more than he understood the nature of his attraction towards such subjects. And one can understand his irritation with impertinent speculations.

Whatever one thinks of his paintings, Balthus is a fascinating and symptomatic case and an inexpensive anthology of colour plates is much needed. It is a pity that Thames and Hudson’s is supplied with a pompous essay by the artist’s eldest son, asserting, for example, that the ‘very youth’ of the girls his father painted ‘is the emblem of an ageless body of glory, as adolescence (from the Latin adolescere, to grow towards) aptly symbolises the heavenward state of growth to which Plato refers in the Timaeus’. The Catalogue raisonné provides a useful directory of drawings as well as paintings, and includes much valuable material (especially the photographs of untraced works) and information – although not as much information as we might have hoped. From Fox Weber’s biography (which is not respectful of the artist’s patrician posture but takes him seriously as an artist) we learn a good many facts not disclosed in the catalogue about the history of the pictures, about the identity of the sitters, and about the artist’s methods. He explains that The Guitar Lesson was rejected by the Museum of Modern Art at the instigation of Blanchette Rockefeller when Balthus’s dealer Pierre Matisse tried to donate it. He points out that Betty Leyris, the model for Alice, had come to Paris from England as a Bluebell Girl. Fox Weber also explains that plaster dust was used to create the textures in one of the artist’s late landscapes. The preliminary essay by Jean Clair in the Catalogue raisonné is a philosophical meditation on the artist and has little to say about any particular work. Balthus was alive when it was written and this helps explain the obsequious and obscure manner. It would have been very much better to reprint some older critical essays – Sabine Rewald’s or John Russell’s for the Tate Gallery retrospective of 1968 – and some historic texts, such as Artaud’s catalogue preface for Balthus’s 1934 exhibition at the Galerie Pierre.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.