Sculpture need not be a bronze statue of a town councillor or a marble figure of a goddess, respectfully plinthed in gallery or plaza; or a curvaceous wooden form strung like a harp which we gaze at in dumbfounded silence. These days, it may well be a drystone wall winding between trees before burying its end in a lake, like the great Norse serpent for ever drinking the world’s waters dry. Or a cairn on a Highland headland with a fire flaming inside it. Or a longboat made of stakes and stones and turf, grounded in the undergrowth of a forest.

These works often use materials that have come to light in the place itself – leaves, rubbed red stones, dry sticks, thorns, the dark fluid from mushroom gills, stones picked from scree, blocks of snow and slivers of ice, earth, deer-dung, scrap iron, fern fronds, spruce thinnings and off-cuts. In this, the land artists are following the footsteps of the original Australians, who ground their ochres from earth in rock holes next to the overhangs which they adorned with fish and birds and lizards and spirit-figures. They are also working as nearly as humans can to the processes of nature itself. If you look at the photographs by Paul van Vlissingen taken monthly from one August to the next at Rudha Cailleach, or Witches’ Point, on the north shore of Loch Maree, you find you’re watching a mobile image, pregnant in each of its 13 stages, the more so because it alters so much as the winds and currents urge and reposition the four types of stone that compose the spit. Now it resembles the tail of a ray or skate, now it’s a sea-tangle head, now it’s a hand whose forefinger points westward. Sometimes it settles down as the head of a bear with an eye and snout that look east in July, west in the second August. If the images were printed on successive pages of one of those tiny flick-books, the tongue of shingle would lash to and fro like a dog shaking a rat.

Compare this work of nature with Spiral Jetty, which Robert Smithson built out into Great Salt Lake in Utah thirty years ago. It’s more neatly coiled than the spit at Rudha Cailleach. Both change continually, the one in its shape, the other in its invisibility; indeed Salt Lake rose recently and drowned the Jetty. At some stage in the submersion it must have become a tapering tongue, finally perhaps a mere stub. Smithson, an adventurous character (who was killed when flying a light aircraft to look at one of his works from above), might have welcomed the flood – he was working with the dirt and gravel of the desert and knew his work was exposed to weathering. The land artists are at ease with change. They go beyond Henry Moore’s pleasure in the greening of his bronzes by oxidation (especially near the sea). Talking to John Fowles in 1987, Andy Goldsworthy came out with this wonderfully relaxed notion: ‘Ten years ago I made a line of stones in Morecambe Bay. It is still there, buried under the sand, unseen. All my work still exists, in some form.’

That is of course true of all matter: dust particles from the canvas and pigment of the Mona Lisa will blow about the world some day. The difference is that the land artists usually garner their materials from the place where the work finally blossoms; and they process these thorns, stems, stones and feathers as little as possible before embodying them in their works. Chris Drury’s Whale Bone (1993), illustrated in his recent Silent Spaces, is ‘simply’ a pilot-whale vertebra with 13 ochre lines etched into each of the twin tines where the upper bone structure forks. The symmetry of its ‘wings’, the converging ridges in its ‘face’, the meerschaum shadings of boney stuff itself are untransmuted. Goldsworthy’s sea-urchin-like icicle cluster, made in the winter of 1987, consisted of icicles ‘with their thick ends dipped in snow then water, held until frozen together’. He rearranged the ice daggers – that is all. Their ribbing, their smoothness or roughness, are as the freezing of the water moulded them.

All that is left of the natural material used by Picasso or Michelangelo is some salient property – the hard white sheerness of marble, the egg-yellowness of chromate. The materials of the land artists – the bush, the tree, the moor from which the material has cropped up – retain their fibrousness or graininess, dirtiness or translucency, as nearly as can be in their natural state.

This already typifies, even stereotypes, the land artists too much. They are not a school or group, although later it will be worth considering why so many artists tended this way at this time. What does link them, inside their luxuriant variety? The most austere among them, Richard Long, makes his works by walking, shuffling, treading. Many of them have probably been seen only by his camera. He fashioned a circle in the gibber-desert of the Hoggar region of the Sahara by clearing the gravel and shingle, leaving the dusty sand. He also made a straight line pointing towards a blunt tusk of mountain – the result is a minimal artefact, forming as distinctively human a trace as Man Friday’s footprint on the beach. Probably the circle and the line are gone by now, overlaid by sifting minerals. The (usually) black and white photographs complete Long’s obsessional ritual. Near my home in Cumbria, Sally Matthews has worked very differently. In A Cry in the Wilderness (1990), two hounds jump over a ragged drystone wall in the permanent twilight of Grizedale Forest. Their colours are rendered in the black of peaty mud, the bronze of stripped branches. Although the artist used fondu cement on a rabbit-wire armature to firm up the crumbliness of the earth, the details are crafted from found materials. The tendon behind one dog’s hindleg is created by a minor root springing from the taproot that makes the limb. Follow the dogs over the dyke and down the bank to a beck and you see a third dog trailing a deer made from branches, twigs, withered grasses, peat. The drab stems and blades that make her coat precisely imitate the look of a hind starving after a hard winter. They remind us that deer make and remake themselves by ingesting grass.

Matthews is a consummate figurative artist. When my Doberman Cross jumped over the wall beside her work, the likeness was exact – the athletic thrust of the hind leg, the avid jut of the head. Long is at the other end of this gamut, a devotee of abstraction, of number and geometrical form. What links them is that both work with the components of the place, in the place, labouring outdoors for many hours at a time and leaving the work where it was made, to take its chance among the rotting and the blowing.

These artists delight in the growing and slow forming of things, they ease themselves into the happening of nature and try to work as its processes do. Stones settle, water freezes, buds unfurl into leaves. On the plateau of the Cairngorms in central Scotland, which is virtually an Arctic island in the temperate zone, prolonged extreme cold has formed patterns like pointilliste paintings, or weaving, on the mountainous moorland. You would swear, as you look out over the ribbed and scalloped surfaces, the marled blue-greys and browns and olive-greens, that they had been designed. Freezing and thawing have ‘sorted and heaved large boulders and soil into a network of gelifluction lobes’, as the naturalist Adam Watson puts it. Nothing could be less purposeful. This beautiful marking of the land, which works on the planes of colour, relief and texture, has simply come about.

Coming nearer to the animate: according to the research of an inspired zoologist at Glasgow University called Mike Hansell, several quite different animals craft the ground, in the course of their nest-building, into remarkably regular patterns. The stubby earthen nests of Gentoo penguins are evenly spaced and sized, like circular tesserae with channels between them. Mole-rats and termites in Southern Africa also build consistent patterns of circular mounds, called mima prairie. Scrub fowl do the same in northern Australia, making a terrain which looks so deliberately planned that their nests have been taken for Aboriginal middens. These animals don’t intend to create symmetry, let alone delight in it. The spacing probably flows from their need to be at a convenient distance from their neighbours.

Coming finally to the consciously created: we know that human activity constantly and typically creates patterns that give us pleasure, as they are meant to, through their consistency – the repetition of pattern across a carpet, or loops or stripes across a knitted fabric. (Metre, rhyme and recurrent melody appeal to the same pleasure in recurrence, and in variations on it.) The mountain, the mole-rat, the weaver (and the poet) all act, whether aware of it or not, in a way that gives rise to forms we rejoice in because they are not chaotic.

Goldsworthy has said that ‘the way my walls are made, stone upon stone, is like growth.’ An installation he made out of broken branches in spring last year for an exhibition curated in Glasgow by Mike Hansell looked like a nest built by a bird from dried-out, crooked, knotty twigs and branches, without following a plan, letting the hands (or claws and beak) weigh up and the eye assess, until the outcome felt right. That this is one of Goldsworthy’s preferred forms is clear from Time, his first major publication for four years, which includes a chronology of his career.

If you happen on a real nest, or a clutch of eggs laid by a wayward hen well away from the farmyard, the stoun of delight that goes through you is a recognition of order achieved in the midst of what sometimes seems like the general stramash – the shattered stone of scree, the litter of splintered and rotted debris on the floor of an unmanaged forest, the spongy black jetsam on a river bed. Among all this, there it is, calmly perfect: the bundle of hay-wisps knit into circles, making a cup, the four or five eggs, rounded and intact. If we’re lucky, we come on a piece of land art with the same sense of surprise. Grizedale Forest Park, in a leafy dale between Windemere and Coniston, teems with amazing works in wood and stone. When I first walked about in it twenty years ago, there was no leaflet listing numbered pieces, and as we walked along foresters’ tracks, there, unexpectedly, was a channelled tree held horizontal on stilts, with water running down it. Was it a relic of old woodcraft or a necessary drain? It was Wooden Waterway (1978) by David Nash. What delighted me was the slender pour of the translucent water, and the way the thing looked almost like an accident of nature, a fallen sapling become a duct. A little further on, perched on a pair of ‘goalposts’ straddling a dip in the track were a dozen crows, made from the offcuts of pointed fenceposts. Creosoted black, the little toys with two wedges for wings and two more for the head were so crow-like that they reminded us of the sinister flock that gathers on the school climbing-frame in The Birds. A little further on a horizontal timber was loping through a clearing on four branch-legs, perfectly mobile, perfectly still – Nash’s Running Table (1978).

Now works of monumental presence look out at you from between the trees. Lifelike boars and wolves and elephants. A group of older men with rounded shoulders, huddled in conversation. Wooden axes uncurling from the ground like seedlings. David Kemp’s Ancient Forester (1988), twenty feet high, leaning on his axe above the car park with antlers growing through his green hat and bunions on his toes bulging out of the wood. Goldsworthy’s massive Sidewinder (1984-85), an anaconda of pinned-together spruce trunks, swerving off between the boles of the still-living trees. Families cycle through the forest, tracking down the pieces, laughing at Andy Frost’s Red Indian Chief (1985) with smoke signals puffing up from his headdress, wondering at Goldsworthy’s Seven Spires (1984) that taper finely from the forest floor almost to the needle canopy. (They’re now collapsing, as he had anticipated.)

This tribe of creatures, poised between organism and artefact, can be found everywhere now, in Kielder Forest in Northumberland and the Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire and Loch an Eilean in Speyside, on the banks of the Eden upstream from Carlisle and the south bank of the Tyne in Gateshead and on an islet in the middle of the Teign in Devon, in woodland on Silkstone Common west of Barnsley and on a landscaped spoil-heap near Stanley in County Durham, on the shore of a lochan in North Uist and in a dewpond on Malling Down in Sussex. Old materials are being recycled into half-familiar forms: David Kemp’s massive idols, an iron-master and a miner, made out of transformer casings from Northern Electric’s works in Newcastle, Goldsworthy’s cone built of flat scrap-iron pieces on the Gateshead bank of the Tyne. People use them. They climb onto the knees of Kemp’s idols to be photographed. They leave heartfelt messages. On Tyneside, near the soaring slim piers of the new railway bridge, Colin Rose has made a great arc of silver-white alloy with a sphere gleaming at its zenith – Rolling Moon. In black felt-tip near its base I read: ‘I will always love my beloved boyfriend Alan Cousins for eva 12.5.91.’ Is this vandalism? According to the recently retired maestro of Grizedale, the forester Bill Grant, only one thing has ever been destroyed there: the crows, which were trashed by a school party in the late 1980s.

By and large it is nature which puts a term to these things. In time, naturally, wood rots from the ground up, wind topples trees onto walls, metal oxidises, moss and fungus infest and blear, water rises, submerges, effaces. The Running Table has been renewed three times but the present manager of Grizedale, Adam Sutherland, is dubious about this policy and knows that immaculate gardening is hardly possible – it took ten men a week to clean forty tons of fallen pine needles off a piece of Donald Urquart’s, laid out in chips of radiant-white Skye marble. Goldsworthy’s Spires may well be left to decay where they lie, and the artist himself is unworried about this. Such things ask to be neither conserved nor restored. They don’t live by exquisite patina, precise nuance of colour, minute detail or the like. A certain roughness, as of a field stone or the bark of a tree, is of their essence, however much skill is involved in their making. Peter Randall-Page’s Granite Song (1991), on the Teign near Chagford, is a Dartmoor boulder sawn in half, each facet carved with his characteristic symmetry and finesse into a tubey, intestinal figure. No roughness here (except in the husk of the stone). What makes it kin to the other works I’ve mentioned is the effect of nature having blossomed into a brand-new form.

Land artists seem singularly free of ideological baggage, tending to talk practically about how they make their works – how the available materials suggested a shape or feature, prompting a new outgrowth from their accustomed styles. When Matthews writes about Cry in the Wilderness that animals have ‘senses and a reality that we have lost or never had’, or Kemp writes about Ancient Forester that ‘he lives in responsible husbandry with nature, and seeks a symbiotic relationship with his environment and its renewable resources,’ we recognise notions from green thinking. The dismaying findings of Rachel Carson in Silent Spring are ingrained in us now. So, positively, are Darwin’s demonstrations of how life works, how its ‘self-developing energies’ unfold, in that unobtrusive phrase from his diary which at once disposes of all that is supernatural and plants us in the world as it really is. Atomic nuclei are split, genes are inserted into or removed from organisms – such exquisite fingerings into the pith of matter are now potent in our world, for ill and for good. The land artists don’t look beyond, to gods or demons; they deal with the trees, the rocks, the waters as they are, drawing material from them, returning it to them.

The work of Goldsworthy’s that has most found me is one he doesn’t distinctly remember making. His book Hand to Earth contains a black and white photograph called Bow Fell, Cumbria: May 1977. Four big, rough flakes of rock balance on a crevice in the face of a sunlit crag. The rock is grainy as pumice. It’s photographed so that infinite thousands of feet of cliff might as well stretch above and below this poised structure. The flakes must have gone long since, destabilised by ice, snow, gravity, even one of our occasional earth tremors, which have shaken cups off hooks in Carlisle and shuddered a huge chunk out of a rock-climb on Kern Knotts, Wasdale, called (unbelievably) Sepulchre. This work of Goldsworthy’s finds me because I learned to climb on Bow Fell and I know what it is to cling by toes and finger-ends to the hundred-metre face of its eastern buttress. Touch, balance, friction, leverage, precarious equipoise, height, drop: all climbing is embodied in those four stones. The doyen of Scottish rock-climbers, Cubby Cuthbertson, who recently made the first ascent of Britain’s most imposing route, the colossal Atlantic-facing arch on the Hebridean island of Pabbay, remarked while filming the climb that what he loved was aesthetic, the textures of the rock. I have no idea whether Goldsworthy had to climb to make his Bow Fell sculpture, but what it does, in its rough, transient, apparently abstract way, is to compress into one knot of stone the complex of sensations and thoughts which seethe in me as I occupy focal points on the face of the earth.

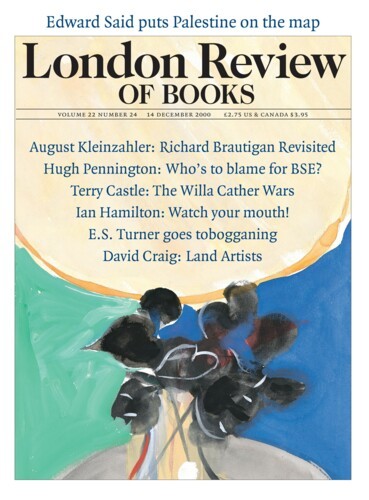

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.