Fine phrases about the freedom of the individual and the inviolability of the home were exchanged between the Minister of State and the Prefect, to whom M. de Sérisy pointed out that the major interests of the country sometimes required secret illegalities, crime beginning only when State means were applied to private interests.

If ever a man feels the sweetness, the utility of friendship, must it not be that moral leper called by the crowd a spy, by the common people a nark, by the administration an agent?

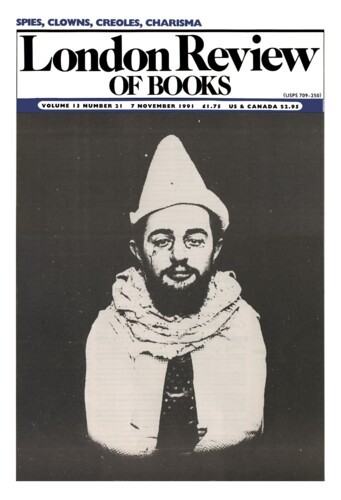

Honoré de Balzac: A Harlot High and Low

Those who complain of the banality of American political life seem at first review to have every sort of justification. Political parties are vestigial; the ideological temperature is kept as nearly as is bearable to ‘room’; there is no Parliamentary dialectic in Congressional ‘debates’; elections are a drawn-out catchpenny charade invariably won, as Gore Vidal points out, by the abstainers; the political idiom is a consensual form (‘healing process’, ‘bipartisan’, ‘dialogue’) of langue de bois and the pundits are of a greyness and mediocrity better passed over than described. Periodic inquests are convened, usually by means of the stupid aggregate of the opinion poll, to express concern about apathy and depoliticisation, but it’s more consoling to assume that people’s immense indifference is itself a wholesome symptom of disdain.

Yet now and then, there are thumps and crashes behind this great, grey safety-curtain, and unsightly bulges appear in it, and sometimes great rips and tears. Politics here a bit trite, you say? Perhaps. But the following things really happened. President Kennedy was shot down in the light of broad day. His assassin was murdered on camera while in maximum security. Richard Nixon’s intimates fed high-denomination dollar bills into a shredder in order to disguise their provenance in the empire of – Howard Hughes? Marilyn Monroe fucked both Kennedy brothers before taking her own life, if she did indeed take it. Frank Sinatra raised money for the Reagans and acted as at least a confidante to the First Lady. Norman Podhoretz’s son-in-law Elliott Abrams, while working as Reagan’s Assistant Secretary of State, dunned the Sultan of Brunei for a $10 million backhander to the Contras and then lost the money in a Swiss computer error. Ronald Reagan sent three envoys with a cake and a Bible to Tehran to discuss an arms-for-hostages trade with the Ayatollah Khomeini. Robert MacNamara went to a briefing on Cuba believing that it was more than likely that he would not live through the weekend. The Central Intelligence Agency was caught, in collusion with the Mafia, plotting to poison Fidel Castro’s cigars. Ronald Reagan’s White House was run to astrological time, and its chief spent his evenings discussing Armageddon theology with strangers. Oliver North recruited convicted narcotics smugglers to run the secret war against Nicaragua. George Bush recruited Manuel Noriega to the CIA. As the Watergate hounds closed in, Henry Kissinger was implored to sink to his Jewish knees and join Richard Nixon in prayer on the Oval Office carpet, and complied. Klaus Barbie was plucked from the SS ‘Most Wanted’ list and, with many of his confrères, given a second career in American Intelligence. J. Edgar Hoover amassed tapes of sexual indiscretion in Washington, partly for his own prurient needs and partly for the ends of power. He caused blackmail letters to be sent from the FBI to Dr Martin Luther King, urging him to commit suicide.

Historians and journalists have never quite known what to do about these sorts of disclosure. They have never known whether to treat such episodes as normal or exceptional. It is, for example, perfectly true to say that the whole Vietnam intervention began with a consciously contrived military provocation in the Gulf of Tonkin, followed by a carefully-told lie to the Senate. But can we tell the schoolchildren that? Then again, it now looks very much like being established that the Reagan-Bush campaign in 1980 went behind President Carter’s back and made a private understanding with the Iranians about the American diplomatic hostages. But those hostages were the original cause of the yellow ribbon movement! Can a piece of fraud and treason really have been the foundation of the storied ‘Reagan revolution’?

Contemporary historians like Theodore Draper, Arthur Schlesinger and Garry Wills, or political journalists like Seymour Hersh, Lou Cannon and Robert Woodward, deal with this difficulty in various ways, but seldom succeed for long in firing the general consciousness. This is because they are either apologists for power (Schlesinger, Woodward) or its intimates (Schlesinger, Woodward) or politically conditioned to disbelieve the worst (Schlesinger, Woodward). Men like Wills and Draper, on the other hand, are almost too bloody rational. They are careful to speak truth to power and to weigh evidence with scruple, but they are wedded to the respectable and predictable rhythms of academe, of research, of high and serious mentation. They find and pronounce on corruption and malfeasance, and gravely too, but it’s always as if the horror is somehow an invasion or interruption. This is why the permanent underworld of American public life has only ever been captured and distilled by novelists.

Mass culture in America, contrary to report, has no great resistance to believing in official evil. The citizenry stoically watches movies in which the cop is the criminal, the President is the crook, the CIA is a double-cross and the dope is dealt by the Drug Enforcement Administration. The great cult film of all time in this respect is George Axelrod’s and John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate, withdrawn from circulation after the Kennedy assassination but now available again in cassette form. And the great artistic and emblematic coincidence of the movie is the playing of the good guy by Frank Sinatra – the only man to have had a real-life role in both the Kennedy and Reagan regimes, as well as a real-world position in the milieu of organised crime and disordered ‘Intelligence’. The Manchurian Candidate began as a novel by Richard Condon, who with Don DeLillo has done more to anatomise and dramatise the world of covert action than any ‘authorised’ chronicler. Before discussing Norman Mailer’s magisterial bid for dominance in this field, I want to use Richard Condon to anticipate a common liberal objection – the objection that all this is ‘conspiracy theory’.

One has become used to this stolid, complacent return serve: so apparently grounded in reason and scepticism but so often naive and one-dimensional. In one way, the so-called ‘conspiracy theory’ need be no more than the mind’s needful search for an explanation, or for an alternative to credulity. If one exempts things like anti-semitism or fear of Freemasons, which belong more properly to the world of post-Salem paranoia and have been ably dealt with by Professor Richard Hofstadter in his study The Paranoid Style in American Politics, then modern American conspiracy theory begins with the Warren Commission. There had been toxic political speculation at high level before, as when certain people thought that there was something too convenient about the Lusitania for President Woodrow Wilson, and too easy about Pearl Harbour for President Franklin Roosevelt – both of these, incidentally, hypotheses which later Churchill historians are finding harder to dismiss – but such arguments had been subsumed in the long withdrawing roar of American isolationism. The events in Dealey Plaza and the Dallas Police Department in November 1963 were at once impressed on every American. And the Warren Commission of Inquiry came up with an explanation which, it is pretty safe to say, nobody really believes. Conspiracy theory thus becomes an ailment of democracy. It is the white noise which moves in to fill the vacuity of the official version. To blame the theorists is therefore to look at only half the story, and sometimes even less.

To take an obvious example, nobody refers to Keith Kyle as a ‘collusion theorist’ because he explodes the claim that Britain, France and Israel were not acting in concert in 1956. The term ‘organised crime’, which suggests permanent conspiracy, is necessary both to understand and to prosecute a certain culture of wrongdoing. And you may have noticed that those who are too quick to shout ‘conspiracy theorist’ are equally swift, when consequences for authority and consensus impend, to look serious and say: ‘It’s more complicated than that.’ These have become standard damage-control reflexes.

In his Kennedy assassination novel Winter Kills, Condon’s protagonist is Nick, the brother of the slain President. He has a grown-up adviser and protector named Keifetz: ‘Nick used to think that there was the Democratic Party and the Republican Party. It had taken Keifetz a long time to explain why this wasn’t so, but after that, after Nick had been able to comprehend that there was only one political party, formed by the two pretend parties wearing their labels like party hats and joining their hands in a circle around their prey, all the rest of it came much easier.’

That’s put slightly cheaply: all the same, it makes more sense than the drear convention that two opposing parties contend in the ‘marketplace of ideas’. Nick has two reflections on the way in which official truth is manufactured and promulgated in America, and on the ‘Commissions’ (one need only think of our Royal ones like Denning and Bingham and Pearce) which act as vectors in the process. First, he enquires: ‘Was the history of all time piled up in a refuse heap at the back of humanity’s barn, too ugly to be shown, while the faked artifacts that were passed around for national entertainments took charge in the front parlour? Could the seven hack lawyers of the Pickering Commission, with a new President for a client, decide that two hundred million people could not withstand the shock of history?’ It was the argument of Chief Justice Earl Warren in 1964, and of the Tower Commission members in 1987 when they ‘reported’ on Iran-Contra, that ‘the American people’ could not bear too much reality. And even the chief attorney for the farcical Senate-House inquiry into the latter affair, Mr Arthur Liman, conceded to Seymour Hersh that he and his colleagues had meant to find the President blameless and thereby spare the masses the supposed agony of impeachment.

Nick goes on to reflect that:

The Pickering Commission had operated like arms, elbows and fingers upon a silent keyboard. They had played all the notes – the score was surely there to be read, but they would not allow it to be heard. The Commission had announced Stephen Foster when they were actually playing Wagner. Surely, critics who had followed the true score should have pointed that out?

A good question, but perhaps one that only literature can answer. ‘Critics’ – the press, the academics, the think-tankers – do not care to admit that they missed the big story or the big case. Nor do they get their living by making trouble for the Establishment.

A novelist, however, can listen for the silent rhythms, the unheard dissonances and the latent connections. ‘Conspiring’, after all, means ‘breathing together’. Why not check the respirations? He can also do what quotidian academics and scholars are afraid to do – which is to ruminate on the emotions and the characters and the motives. Most instant reporters are so wised-up that they become innocent: taking politicians at their own valuation. Thus Kennedy the youthful and impatient, Carter the introspective, Nixon the driven, Reagan the folksy and so forth, ad, if not indeed well in advance of, nauseam. Then the scholars move in to give needed ‘balance’ and ‘perspective’ to these popular fables. A novelist need not do either He can dispense with banality. He can raise intrigue to the level of passion.

She would not have been a liberal; a courtesan is always a monarchist.

Honoré de Balzac: A Harlot High and Low

I once got into trouble with Norman Mailer by asking him, on an every-man-for-himself chat-show with Germaine Greer, about his fascination with the Hubert Selby side of life. Boxing gyms, jails, barracks, the occasions of sodomy. The practice of sodomy. He appeared riveted, in book after book, by its warped relation to the tough-guy ethos. Had this ever been a problem for him personally? I miscued the question, and Mailer thought I was trying to call him some kind of a bum-banger. He later gave an avenging interview to the Face, asserting that he was the victim of a London faggot literary coterie, consisting of Martin Amis, Ian Hamilton and myself. (Amis and I contemplated a letter to the Face, saying that this was very unfair to Ian Hamilton, but then dumped the idea.) Now here is Mailer attempting the near-impossible: that is to say, a novel about the interstices of bureaucracy which, without any Borgesian infinite libraries or Orwellian memory holes, can summon the sinister and the infinite. Doing it, moreover, at a level of realism which vanquishes Condon and DeLillo while leaving spare capacity for the imagination. And here is Harry Hubbard, his outwardly insipid narrator. Hubbard is a white-collar type of CIA man, a ‘ghost’ writer of planted texts, who is vicariously thrilled by the knowledge that he is working with ruthless men. He meets his ‘other half’ of the Agency, Dix Butler, a cruel exploiter of local Berlin agents, and has a gruelling soirée with him on the Kurfürstendamm which culminates when

‘Let me be the first,’ he said, and he bent over nimbly, put his fingertips to the floor and then his knees, and raised his powerful buttocks to me. ‘Come on, fuck-head,’ he said, ‘this is your chance. Hit it big. Come in me, before I come back in you.’ When I still made no move, he added, ‘Goddamnit. I need it tonight. I need it bad Harry, and I love you.’

This blunt offer, which stirs Hubbard more than he wants to admit (‘two clumps of powered meat belonging to my hero who wanted me up his ass, yes I had an erection’), enables him to summon the heft to take his first woman that very night. Ingrid turns out to have some qualities in common with her fellow Teuton, the German maid Ruta in An American Dream: ‘She made the high nasal sound of a cat disturbed in its play... but then, as abruptly as an arrest, a high thin constipated smell (a smell which spoke of rocks and grease and the sewer-damp of wet stones in poor European alleys) came needling its way out her’ (An American Dream). ‘A thin, avaricious smell certainly came up from her, single-minded as a cat, weary as some putrescence of the sea... pictures of her vagina flickered in my brain next to images of his ass, and I started to come’ (Harlot’s Ghost).

Berlin and bildungsroman, you say. OK, so he’s a camera: get on with it. But, self-plagiarism apart, I think that Mailer is distilling an important knowledge from his many earlier reflections on violence and perversity and low life. As Balzac knew, and as Dix Butler boasts, the criminal and sexual outlaw world may be anarchic, but it is also servile and deferential. It is, to put it crudely, generally right-wing. It is also for sale. (Berlin has seen this point made before.) Berlin was the place where the CIA, busily engaged in recruiting hard-core ex-Nazis for the Kulturkampf against Moscow, first knew sin. First engaged in prostitution. First thought about frame-ups and tunnels and ‘doubles’ and (good phrase, you have to admit) ‘wet jobs’. More specifically – because this hadn’t been true of its infant OSS predecessor in the Second World War – it first began to conceive of American democracy as a weakling affair, as a potential liability; even as an enemy.

Mailer strives so hard to get this right that he’s been accused of not composing a novel at all. But as the pages mount one sees that this is one writer’s mind seeking to engage the mind of the state. The Imagination of the State is the name of a CIA-sponsored book on the KGB and fairly early in Harlot’s Ghost its eponymous figure, ‘Harlot’, a James Angleton composite, says of the Agency that ‘our real duty is to become the mind of America.’ How else to link the Mafia, Marilyn Monroe, the media, the Congress, Hollywood and all the other regions of CIA penetration? ‘The mind of America’. A capacious subject. As Harry minutes while he’s still a green neophyte: ‘In Intelligence, we look to discover the compartmentalisation of the heart. We made an indepth study once in the CIA and learned to our dismay (it was really horror!) that one-third of the men and women who could pass our security clearance were divided enough – handled properly – to be turned into agents of a foreign power.’ Which, in one sense, they already were. As Kipling made his boy spy say, you need ‘two separate sides to your head’. The boy, of course, was called Kim.

A continuous emphasis, then, is placed on the concept of ‘doubling’ and division. It’s expressed as a duet between ‘Alpha’ and ‘Omega’ which may not be as obvious as at first appears, since ‘Omega’ was the name of the most envenomed Cuban exile organisation. Homosexuality ‘fits’ here – even, on one occasion, androgyny – as being supposedly conducive to concealment and ambivalence. Same-gender infidelity, too, can be conscripted. So can the double life led by the ‘businessmen’ and ‘entertainers’ linked to organised crime. But Mailer calls his novel ‘a comedy of manners’ because it treats of people who have been brought up ‘straight’, as it were, and who need a high justification for dirtying their hands. One of the diverting and absorbing features of the book is its fascination with the WASP aesthetic. Not for nothing was OSS, the precursor of the CIA, known during its wartime Anglophile incubation as ‘Oh So Social’. A proper WASP – former CIA Director George Herbert Walker Bush swims into mind – can have two rationales for entering the ungentlemanly world of dirty tricks. One is patriotism. The other is religion. Hubbard finds a release from responsibility in both:

I eschewed political arguments about Republicans and Democrats. They hardly mattered. Allen Dulles was my President, and I would be a combat trooper in the war against the Devil. I read Spengler and brooded through my winters in New Haven about the oncoming downfall of the West and how it could be prevented.

Apart from its affinity with the Condon extract earlier about the irrelevance of everyday ‘politics’, this can be read as an avowal of Manicheism and thus as the ideal statement of the bipolar mentality. I’ve heard and read many CIA men talk this way, though usually under the influence of James Burnham (and Johnnie Walker) rather than Osvald Spengler, and found it easy to see that their main concern was sogginess on the domestic front – the enemy within. Hence the battle, not just against the Satanic ‘other’, but for the purity of the American mind. And, since the Devil can quote Scripture, it’s an easy step to mobilising the profane in defence of the sacred. Facilis descensus Averno. ‘The Agency’ becomes partly a priesthood and partly an order of chivalry. Recall that James Jesus Angleton, though he detested his middle name for its Hispanic, mother-reminiscent connotations, was an ardent admirer of T.S. Eliot’s Anglo-Catholic style and once startled a public hearing by quoting from ‘Gerontion’. The norm at Langley, Virginia is Episcopalian, though Mormons and Christian Scientists and better-yourself Catholics are common in the middle echelons, and Mailer has a go at creating a Jewish intellectual agent who is also, perhaps avoidably, the only self-proclaimed shirt-lifter.

It is an intriguing fact, a fact of intrigue, possibly the most ironic fact in the modern history of conspiracy, and arguably the great test of all who believe in coincidence, that on 22 November 1963, at the moment when John Fitzgerald Kennedy was being struck by at least one bullet, Desmond FitzGerald was meeting AMLASH in Paris. FitzGerald, the father of the more famous Frances, was a senior exec at the CIA. AMLASH was the CIA codename of a disgruntled and ambitious Castroite. FitzGerald handed AMLASH a specially-designed assassination weapon in the shape of a fountain pen, and discussed the modalities of termination. Emerging onto the wintry boulevards, he found that his own President had been murdered. A bit of a facer.

Conspiracy is, more than any other human activity, subject to the law of unintended consequences (which is why it should always be conjoined to cock-up rather than counterposed to it). Jonathan Marshall of the San Francisco Chronicle, who is in my view the most sober and smart of those who study conspiracy theory, has an elegant and minimal guess about CIA reaction to this disaster. ‘Richard Helms asked himself: “Is my Agency responsible for this?” and answered: “I certainly hope not.” ’ The CIA, in other words, knew that both Ruby and Oswald were involved in the febrile politics of Cuban exile resentment, and the scuzzy world of the fruit-machine kings. The CIA therefore prayed that this footprint would not be discovered. It did more than pray that this was not a ‘blowback’ from one of its own criminal sub-plots. By the neat device of Helms’s appointment to the Warren Commission, it was able to postpone the revelation of its involvement by more than a decade. If the Warren Commission had known what the Church Committee later found out, American history and consciousness would now be radically different. But the meantime saw several more domestic assassinations, a war in Asia and the implosion of a felonious President who had also relied on Cuban burglars, and in that meantime the American mind had become in more than one sense distracted.

This is ideal psychic territory for Mailer, who surveys with an experienced eye the Balzacian cassoulet of hookerdom, pay-offs, cover-ups, thuggery, buggery and power-worship from which the above morsels have been hoisted. ‘Give me a vigorous hypothesis every time,’ exclaims Harlot/Angleton at one point. ‘Without it, there’s nothing to do but drown in facts.’ His protégé Hubbard wonders whether it’s ideologically correct to be too paranoid, or whether there exists the danger of not being paranoid enough. Mailer registers these oscillating ambiguities brilliantly in the minor keys of the narrative and in the small encounters and asides. He does less well when he tries to supply his own chorus and commentary, as he attempts to do by means of a lengthy epistolary sub-text. Hubbard, ‘on station’ with the real-life E. Howard Hunt in Uruguay, writes long confessional letters to Kittredge, Harlot’s much younger and brighter wife and a classic Georgetown bluestocking. One sees the point of going behind Harlot’s back, but this exchange is improbably arch and overly literal, bashing home the more subtle filiations and imbrications that are the real stuff of the novel.

‘Large lies do have their own excitement,’ as Hubbard shrewdly notices. There must have been CIA men who whistled with admiration at the scale of Adlai Stevenson’s deception of the UN over Cuba, and who disgustedly or resignedly went through the motions of reassuring Congress that things were above board. There must also have been CIA men who enjoyed sticking it to the more earthbound, plebeian gumshoes of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI (more Baptists and Adventists than Episcopalians in that racket) and who relished the freedom to travel, to make overseas conquests, to hobnob with Godfathers, to toy with death warrants and the rest of it. Mailer summons their sense of illicit delight very persuasively. Crucial to the skill and thrill was, of course, knowing how far they could go and then going just that crucial bit further. There were laws and customs and codes to be negotiated and circumvented, and these were men with law firms in their families. As Cal, Hubbard’s leathery old warrior WASP of a father, puts it, while seeking to lure President Kennedy into further complicity over Cuba:

‘Always look to the language. We’ve built a foundation for ourselves almost as good as a directive. “Subvert military leaders to the point where they will be ready to overthrow Castro”. Well, son, tell me. How do you do that by half?... Always look to the language.’

Two weeks later, Jack Kennedy sent a memo about Cuba over to Special Group. ‘Nourish a spirit of resistance which could lead to significant defection and other by-products of unrest.’ ‘By-products of unrest,’ said Cal, ‘enhances the authorisation.’

I can just hear him saying it. By looking to the language you find that the secret state, in addition to a mind, possesses a sense of humour and a sexual sense also. The Agency knew, as Angleton’s hero knew in Murder in the Cathedral, that potentates are very flirtatious and need to have their desires firmed up – hence the mentality, very commonly met with among intelligence agents, of aggressive self-pity. The public hypocrisy of the politicians convinces them that they do the thankless, dirty, dangerous tasks: getting the blame when things go wrong and no credit when they go right. (The CIA memorial at Langley has no dates against the names of agents missing in action.) Thus great fealty can be recruited by a superior who sticks by his thuggish underlings. As Kittredge writes to Hubbard, when the excellently-drawn Bill Harvey, a psychopathic station chief, has run afoul: ‘Helms did go on about the inner tensions of hard-working Senior Officers accumulated through a career of ongoing crises and personal financial sacrifice ... Helms may be the coldest man I know, but he is loyal to his troops, and that, in practice, docs serve as a working substitute for compassion.’ Or again, annexing real dialogue for his own purpose, Mailer uses an occasion during the Commission hearings when Warren himself asked Allen Dulles:

‘The FBI and the CIA do employ undercover men of terrible character?’ And Allen Dulles, in all the bonhomie of a good fellow who can summon up the services of a multitude of street ruffians, replied, ‘Yes, terribly bad characters.’

‘That has to be one of Allen’s better moments,’ remarked Hugh Montague.

It’s some help to be English, and brought up on Buchan and Sapper, in appreciating the dread kinship between toffs and crime.

Yet this gruff, stupid masculine world is set on its ears by one courtesan. ‘Modene Murphy’, who is Mailer’s greatest failure of characterisation here, is perhaps such a failure because she has to do so much duty. In the novel as in life, she has to supply the carnal link between JFK, Frank Sinatra and the mob leader Sam Giancana. (Ben Bradlee, JFK’s hagiographer and confidant, says that one of the worst moments of his life came when he saw the diaries of Judith Campbell Exner and found that she did indeed, as she had claimed, have the private telephone codes of the JFK White House, which changed every weekend.)

Because it’s not believable that this broad would write any letters, Mailer’s epistolary account of Modene takes the form of recorded telephone intercepts between her and a girlfriend. These are read by Harry, whose general success with women is never accounted for by anything in his character as set down. He both gains and loses the affection of Modene: the gain seemingly absurdly simple and the loss barely registered. Perhaps Mailer was faced with a fantasy/reality on which he couldn’t improve, but one could hope for better from a friend of ‘Jack’ and a biographer of ‘Marilyn’. Incidentally, what was Modene like in the sack? ‘Its laws came into my senses with one sniff of her dark-haired pussy, no more at other times than a demure whiff of urine, mortal fish, a hint of earth – now I explored caverns.’ This is perhaps not as gamey as An American Dream (‘I had a desire suddenly to skip the sea and mine the earth’), but evidently Mailer’s olfactory nerve has not failed him. Still, one occasionally feels (‘Modene came from her fingers and toes, her thighs and her arms, her heart and all that belonged to the heart of her future – I was ready to swear that the earth and the ocean combined’) that he is pounding off to a different drummer. At one point, losing his grip entirely, he makes Hubbard exclaim: ‘I could have welcomed Jack Kennedy into bed with us at that moment.’

These elements – volatile, you have to agree – all combine to make Kennedy’s appointment in Dallas seem like Kismet. It’s a fair place for Mailer to stop, or to place his ‘To Be Continued’. Ahead lies Vietnam, of which premonitory tremors can be felt, and Watergate, and Chile ... But the place of covert action in the American imagination, and in the most vivid nightmare of that imagination, has been so well established that it will be impossible – almost inartistic – for future readers and authors to consider the subjects separately.

Louis XVIII died, in possession of secrets which will remain secret from the best-informed historians. The struggle between the General Police of the Kingdom and the Counter-Police of the King gave rise to dreadful affairs whose secret was hushed on more than one scaffold.

Honoré de Balzac: A Harlot High and Low

It may seem astounding, after what happened to compromise the Kennedy brothers and Richard Nixon, and after what disgruntled CIA rebels almost certainly did to Jimmy Carter over Iran, that in 1980 a new President should decide simply to give the CIA its head. But in Ronald Reagan’s warped and clouded mind, the fantasy world of covert action demanded such evil clichés as that hands not be tied, kid gloves not be used and the ‘stab in the back’ over Vietnam be revenged. Thus it was only a matter of time before the crepuscular world of William Casey was exposed to view. ‘Affair’ is too bland a word for the Iran-Contra connection. Remember that it involved the use of skimmed profits from one outrageous policy – hostage-trading with Iran – to finance another: the illegal and aggressive destabilisation of Nicaragua. This necessitated the official cultivation of contempt for American law and of impatience, to put it no higher, with the Constitution. It also entailed, since the funding of the racket had to be concealed from the Treasury and State Departments, a black economy. The arms dealers, drug smugglers and middlemen of this dirty budget were to furnish most of the ‘colourful characters’, as Americans found to their dismay that shady Persian marchands de tapis knew more about the bowels and intestines of the White House than, say, the Congress did. This more than licenses the plural in the title of Theodore Draper’s book; one of the very few indulgences he permits himself. The book itself has been abandoned by its English publishers at the last moment, in a flurry of unconvincing excuses.

Draper’s task may be linked to that of an anatomist or dissecter, going coolly about his work while the bleeding and reeking corpse is still thrashing about on the slab. In his mild introduction, he confesses the ‘horror’ he felt when he saw the growing mountain of evidence and testimony that was heaping up in front of him. Nor was it just a matter of meticulous forensic investigation. Two elements of mania pervaded the case and pervade it still. First, the principals in the conspiracy all claimed, and claim, to have amnesia. Second, they all behave as if they had been working for King Henry II. It became a bizarre question of interpreting a President’s desires: protecting that same President from the consequences of his desires and then redefining knowledge and participation so as to elude or outwit the law. Always look to the language. In this case, the giveaway keyword was the ‘finding’ – a semi-fictional document which conferred retrospective Presidential approval for policies that had often been already executed. Ordinary idiom became unusable in this context. Robert Gates, who is now George Bush’s nominee to head the CIA, was at the material time William Casey’s deputy. He told Congress in 1987 that when advised of the ‘diversion’ of funds from the Iran to the Contra side of the hyphen, his ‘first reaction’ was to tell his informant that ‘I didn’t want to know any more about it.’

A strange response, at first sight, from a professional intelligence-gatherer. And how did he know enough to know that he didn’t want to know any more? This absurdity was easily lost in the wider, wilder cognitive obfuscation – did Reagan know? – by which the whole inquiry was derailed. One needs a separate brand of epistemology to attack the question of official ‘knowledge’, which has the same combination of Lear and Kafka that you sometimes find with British ‘official secrecy’. Actually, what is required is the mind of a Mafia prosecutor. Once postulate a capo who tells his soldiers, ‘I want the hostages out, and I want the Nicaraguans to say “uncle”, and I don’t want to know how you get it done and if you get caught I never met you,’ and the cloud of unknowing is dispelled. Fail to conceive of such a hypothesis – and the Congress could not bear that much reality – and there is a ‘mystery’.

This is not the ‘thin line’ of Draper’s inquiry. Relying almost exclusively on the written record and his skill as a historian, he tries to compose a history of the present. But with knowledge, memory and desire left opaque, and without the promiscuity that is permitted to the freelance speculator, all he can do is show – employing their own words and memos – that the American Constitution was deliberately put at risk by a group of unelected, paranoid Manicheans. This in itself is one of the scholarly achievements of the decade.

It’s an amazing bestiary of characters, even when rendered with Draper’s detachment and objectivity. Adnan Khashoggi, Oliver North, Amiram Nir, Michael Ledeen, Robert MacFarlane – the sweepings of the Levant meet the white trash of Washington. Reading Draper, one can discern the road map that leads to BCCI – a banana republic bank which acted as a laundry for both the CIA and Abu Nidal. Indeed, it is the use of banana republic tactics and contacts, picked up in sordid engagements in the Third World, that has marked CIA intervention in American life. This and other considerations led Theodore Draper, earlier, to baptise Reagan’s private government as ‘the Junta’. In the turf wars between different police agencies, and the squabbling over the dirty money, the atmosphere became so fetid that a leak or discharge was inevitable. How appropriate, then, that the story blew, not in some pompous American journal of record, but in what Reagan angrily called ‘that rag in Beirut’ – city of so many recent American nightmares.

Oliver North, with his puffed-out chest and his lachrymose style, his awful martial ardour and his no less awful sentimentality, is the perfect example of a Mailer figure – a superstitious fascist, whose whole entourage was full of self-hating, uniform-loving homosexuals. North’s strong will to obey and his sadomasochism, his sense of betrayal over Vietnam, and his need for revenge in Nicaragua, brought us as close to an American Roehm as was comfortable. It is still uncomfortable to reflect that he was not thwarted by law or by civilian authority.

Some critics have claimed to see a new maturity and acceptance in Mailer’s novel, because it eschews polemic and treats its characters with empathy. I think that this misses the point. In The Naked and the Dead, Mailer was able to produce a fully-realised character, General Edward Cummings, who by making war on his own feminine ‘side’ was enabled to ready himself for the coming struggle for world order, by which of course he meant the post-war American Empire. This demonstrates, as does Harlot’s Ghost, that there is a Mailer high and low, and that he can mobilise his feeling for the profane in order to bring himself to bear on more elevated subjects. ‘What a man of the cloth he would have made!’ says Hubbard of Harlot: ‘The value of his words was so incontestable to himself that he did not question the size of his audience. I could have been one parishioner or five hundred and one: the sermon would not have altered. Each word offered its reverberation to his mind, if not to mine.’ Harlot boasts of ‘the Company’s’ ubiquity among ‘bankers, psychiatrists, poison specialists, narcs, art experts, public relations people, trade unionists, hooligans, journalists ... soil erosion specialists, student leaders, diplomats, corporate lawyers, name it!’ From the little world of Encounter to the more encompassing schemes of James Angleton and William Casey, all of us have been slightly deranged by the work of this giant cultural and political construct. And now, with the unsolved and unpunished penumbra and personnel of Iran-Contra, we have fuel for more and later conspiracy theories. But as the Cold War at last abates, having so wasted our lives and energies, we can blink our opening eyes at the monsters engendered in the long sleep of reason. It is Mailer’s achievement to have summoned the ghosts of paranoia and conspiracy in order to demystify them, and in so doing to have raised realism to the level of fiction.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.