The clamorous whispers of an impending election remind us that the present government must soon devise a plausible electoral campaign. Given the events of the last four years, this will not be easy: on any objective reckoning, almost no government this century will present the electorate with such a record of wilful failure. But, of course, objective reckonings matter little in the outcome of British general elections, and ‘failure’ has several definitions: even from failure many gain, or think they gain, which is why the political system devised by the Conservatives in the Eighties will long outlive Mrs Thatcher. Nonetheless, there will be some testing moments for Central Office, and their campaign is likely to be dominated by a combination of audacity and reticence.

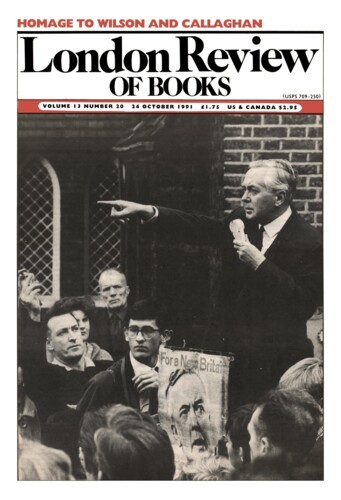

They will certainly follow international fashion and pretend that what they were a year ago they are not today. Just as many of the neo-Brezhnevites who ran the old Soviet Union have miraculously metamorphosed into radical democrats, Ukrainian nationalists, Islamic fundamentalists or Christian mystics, so will the Conservative Party not be the party which almost unanimously supported Mrs Thatcher’s legislation (including the poll tax) until at the eleventh hour the normally docile backbenchers realised the electoral consequences of their actions. We can also be certain that the Party, and its legion of apologists in both the polite and tabloid press, will assure the electorate (once again) that there is no alternative. In an ideological sense this is now probably a rather tatty argument, since the policies with which ‘no alternative’ is associated are themselves largely discredited. The Conservative strategy is, therefore, more likely to take a folk-historical turn: that the alternative to any sort of Conservative government is impossible and that this is historically demonstrated by the disasters of the Wilson and Callaghan governments from 1964 on. This is a powerful argument because it has only to be insinuated, not made explicit; it needs merely to reinforce what are already a number of conventional wisdoms. It will be the Conservatives’ trump.

What has been constructed is a kind of folk memory of decline and disorder which has been wholly disadvantageous to the Labour Party. Such contrived history is of great political significance since much of the present electorate has in fact little or no actual memory of what happened in the Sixties or Seventies and is largely dependent on this received view for its image of Labour as a governing party. Had such a view simply been created by the Conservative Party’s engines of propaganda we might expect time to diminish its force. As a political imperative, however, it is powerful precisely because so many in the Labour Party (both right and left) helped create it or acceded to it. The Labour Party has been peculiarly disabled in the last ten years because so many of its own members have written off its history. Thatcherism was in practice distinctly vulnerable to attack – but not by a party which had denied its own past. How people choose to ‘remember’ the Wilson and Callaghan governments is consequently something to which the Labour Party should urgently attend: only if they ‘remember’ them benevolently (or at least not malevolently) can Labour hope to re-establish itself securely as a governing party. Yet there is still no evidence that the Labour leadership wishes to attend: on the contrary – as Mrs Thatcher did with the Heath government – they seem either to pretend that the Wilson and Callaghan governments did not exist or that they were mistakes for which the Party must endlessly atone.

This received view need not go uncontested. In the first place, we have had 12 years of the Conservative ‘alternative’: the critics of Wilson and Callaghan have had their go and must in turn be judged. In the second, we now have a significant scholarly literature on the Sixties and Seventies. Keith Middlemas, for example, has completed his remarkable study of Britain’s post-war political economy (a remarkable study even if the conclusions the reader draws from this mass of material are – as in my case – not always Professor Middlemas’s), while Michael Artis and David Cobham have edited a detailed and careful examination of the 1974-1979 governments which replaces all previous accounts. What conclusions might the reader draw from all this kind of evidence? Negatively, the historical record suggests that, as against the post-1979 Conservative governments, Wilson and Callaghan glow with a particular lustre. It is true, as the pure-school free marketeers have begun to argue, that Thatcherism was polluted by electoral calculation and a fear of offending vested interests, and to that extent is not the real thing. But it defies sense to believe that a patient who was nearly killed by half a dose would be cured by a whole one. In any case, the real thing has been administered to the Australian and New Zealand economics, and if any free marketeer wishes to see the consequences of that historic ‘betrayal’* he should go and look. Furthermore, given how favourable international circumstances were throughout the Eighties (as compared to the Seventies), it makes what has happened to the British economy even more astonishing.

The reasons for observing the Wilson and Callaghan governments benevolently, however, are not simply that their critics have made an even greater mess – true though that is. Both governments, particularly the 1964-70 government, deserve a much more positive evaluation than they have usually received. Indeed, apart from Attlee’s, the 1964 government is probably the only post-war British government whose record we can read with some satisfaction. While it would be too much to say that in 1970 the horizon was cloudless – among other things, as Middlemas emphasises, the relationship of the trade unions to society and the Labour Party remained highly problematic – the sky was pretty blue. Unemployment and inflation were low, the balance of payments was in equilibrium, productivity growth was by British standards high, it was a peculiarly good period for British manufacturing industry, infrastructural investment remained high, there were important social and institutional reforms. The Government had a discernible sense of the national interest, of what was possible: but there was also a discernible sense of direction and control – a sense fully shared, as Roy Jenkins’s memoirs perhaps surprisingly confirm – by Wilson himself. Within two years – before the 1973 oil crisis overwhelmed the Heath government – many of these gains had been thrown away.

The case for the 1974 government is obviously more difficult: for most people (insofar as they remember anything), it represents exclusively what it to some extent undoubtedly was – low growth, poor productivity, high inflation, strikes, ‘chaos’. But the 1974 government was left as wretched an inheritance as any modern British government – much worse than that left to Wilson in 1964 – which operated insidiously throughout its whole term. Nor, putting it delicately, was the government much helped either by its enemies or friends. Yet Artis and Cobham’s argument that institutionally and politically (despite its well-publicised blemishes) it coped surprisingly effectively is difficult to deny. One way of seeing that government is to imagine what might have happened had it won the 1979 Election and remained in office throughout the Eighties. It seems reasonable to suppose that the great majority of the British people would have (at least) the same standard of living as they do today, the health and education systems would be in significantly better shape, there would not have been two grinding recessions, unemployment would be lower while inflation could scarcely have been higher, there would have been fewer beggars in the streets of all our major towns, the government would have exercised some responsible control of our financial system, thousands of our fellow citizens would not now hold mortgage debts on houses that greatly exceed the value of the houses themselves, manufacturing industry would not now be so skeletal, a working relationship between industry and the government (towards which the Callaghan government was slowly moving) might have partly compensated for the deficiencies of our existing capital market, the very rich would have been less rich and the very poor less poor. Not all these things would have happened, perhaps, but it is a fair bet that some would, and even if only one of them had happened we would be better-off than we are.

One conclusion that we can therefore draw is that since 1945, Labour governments have left the country better than when they found it, and Conservative governments worse. Should the Conservatives lose the next election that conclusion, I think, will still hold. But does it matter? It is not a conclusion that the electorate has drawn, or been allowed to draw. The implication of Middlemas’s study is that it does not much matter. His is a story of an economically-emancipated ‘public’ declining to accept the social foundations of the Keynes-Beveridge settlement, and of an increasingly weak state unable to modernise in unfavourable international conditions and capitulating to powerfully asserted sectarian interests. There are reasons, however, for thinking that it does matter and that we need not read the past quite so pessimistically.

The first is that what appears to be a result of long-term developments is much more historically specific. Contemporaries often see fundamental (sometimes revolutionary) change in events which in hindsight were very much less than that: the French in 1936 after the victory of the Popular Front, or the Americans during the industrial conflicts of 1936-37, are examples. This country in 1978-79 is another: there was a clear tendency to see in trade union behaviour (particularly that of public-sector trade unions) one of these fundamental changes – John Goldthorpe argued then that the ‘phenomenon of prestige’ had ‘decomposed’ and Middlemas seems to agree. It would be unwise to reject this argument entirely: but we might equally suggest that what happened was almost inevitable in the circumstances, particularly given the Government’s decision (which most of its members probably now think to have been a mistake) to hold wage increases to a 5 pet cent norm. The ‘winter of discontent’ ranks high in the demonology of the last Labour government, but we should be careful before accepting it.

There is also a moral argument for thinking that it matters, even if it does not carry much weight with the electorate. Many of the policies of the present government – its housing policies, for instance, or the establishment of the Social Fund – have been tantamount to the creation of poverty and deprivation. The transformation, say, of Central London has been one of the most depressing developments of the last ten years. No doubt the Government did not intend this, and homeless teenagers on innumerable doorsteps are not its responsibility alone: but it is hard to know what else it thought would happen when it concocted the policies in question. The Government’s defenders have implied that we can divorce the moral from the social sphere, that even if we all agree to deplore homelessness, there are no social implications. But we cannot make such a distinction: sooner or later, if we continue on this path, society simply falls apart.

Whether Mrs Thatcher did or did not believe that there was no such thing as society, she certainly acted as if social cohesion had nonetheless to be preserved. For one thing, property becomes threatened if it is not. Her way of securing this increasingly relied upon patriotism and xenophobia, on the one hand, and coercion, on the other. It did her no good. While it is clear that much of the present social dislocation is common to all Western societies and probably beyond the reach of their governments, it is also clear that the ‘alternative’ social cohesion which Mrs Thatcher brought to ‘ungovernable’ Britain has disastrously failed. The quite conscious attempt to replace one form of social relationship by another (and thus one form of social cohesion by another) has had all too practical consequences: we are now very much more likely to be burgled or mugged. Mr Major, to his credit, appears to understand this but it is hard to see what he, as leader of a party very largely shaped in the Eighties, can do about it.

There are two other reasons why it matters whether the present regime survives or not. The first is that the Conservative Government has enormously increased the force of inertia in British society, and the Conservative Party as it is at present constituted depends for its existence on perpetuating that inertia. The Conservative Party has in the past had its share of movers and shakers, and both Mrs Thatcher and those around her, at least in the first years, wished, or said they wished, to move and shake. In practice, however, that was not their primary concern, and the saturnalia of attempted electoral manipulation which characterised her last years further constricted Britain’s social and economic flexibility. A deliberate attempt to purchase social inertia through housing policy, through its encouragement of owner occupation at almost any cost, has also had the effect of making the economy more unstable and more difficult to manage. It might not have been inevitable for the Conservative Party to have gone this way, but by associating herself with its most powerful tendencies, by giving them their head, Mrs Thatcher ensures that the Party now (and Mr Major’s government) is Thatcherite in everything but name. The result is that the Conservative Party and much of British society cling to each other in a kind of dying embrace and the only way to save them both is by uncoupling them.

The second reason is that the state can be restored to its proper place in the British economy only – and perhaps not even then – if the Conservatives are required to leave office. The ideological corollary of structural inertia is the predominance of a narrow and futile orthodoxy of which the Conservative Party is (at the moment) the principal political vehicle. This orthodoxy demands the expulsion of the state from any active part in the country’s economic life, despite the transparent foolishness of this aspiration. The orthodoxy has assumed a quasi-religious aspect, as free trade did before 1914.

We now find ourselves in a position analogous to Edwardian Britain, where it was political death to question the wisdom of free trade despite ubiquitous evidence of the destructive consequences of this: but, unlike the Edwardians, we are without a government able to construct a coherent compensating policy. It is thus impermissible to argue that British Aerospace, Rolls-Royce, Rover or Jaguar should not have been privatised, or that one of them should never have been encouraged to buy another. The result of this silence is that a paralysed government stands helplessly by hoping that what is all too likely to happen does not. But in Britain the degree of inertia is now such that the state, for all its past failings, is one of the few dynamic economic agents which remain. By denying this, the present government has abandoned any kind of responsible action: it is one thing to say that the state cannot pick winners, quite another that it should let winners go bankrupt.

Which returns us to Wilson, Callaghan and the Labour Party, since the current orthodoxy is justified almost exclusively by the apparent ‘failure’ of the state-interventionist policies they practised. If an ideological alternative to the Conservative Government is to be made acceptable to the electorate, both folk memory and the Labour Party will have to change their minds about the 1964 and 1974 governments and the Labour Party will have to do it first. The Labour Party has committed the cardinal rhetorical error of any political party by apologising for its own past: the Conservatives may ignore their own past, but they never apologise for it. Labour has done this partly because of the utopianism of many of its activists – to them the best is always the enemy of the good – and partly because of a certain timid and innocent defensiveness. Labour always plays the game by other people’s rules. A measure of this defensiveness is the extent to which the Labour Party is happy to be thought the ‘caring’ party but is plainly less happy to be thought the ‘competent’ party, even though there seems no logical reason why it could not be both. It thus apologises for the Wilson and Callaghan governments because the activists said they fell below perfection while those in economic and cultural authority said they failed. But there are entirely adequate justifications for these governments which the Labour leadership should start making. Although it seems scarcely possible, the majority of the electorate still believes that the Conservatives are more ‘competent’ economic managers than Labour, and this basically means that they think the Tories are more fit to govern. We can be fairly certain that as an election approaches this belief will become more intense – much to Labour’s detriment. The Labour leadership must, therefore, assert that the Wilson and Callaghan governments were more ‘competent’ than their predecessors and successors, which they were, and sound as though they mean that as a compliment, and also recognise that their policies, though indeed imperfect, were better suited to a sluggish, rather uncohesive society than the alternatives. They might then be able to argue that the rather rough-hewn social democracy with which the Labour Party is historically associated has worked very much more in the national interest than anything else we are likely to have. And that we are more likely to have a productive capitalism under Labour than under its principal opponent. A Labour Party which restores itself to its own past might, having perceived its strengths, accept its weaknesses: namely, that under our present institutional and constitutional arrangements its spells in office may be fitful and unrewarding.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.