Just over a year ago, on the last day of 1986, ‘a small boy called Bilal was crossing an alley in the Palestinian refugee camp of Bourj al Barajneh in southern Beirut. High in a building outside the camp a sniper belonging to the Amal militia was watching the alleyway. When Bilal came into his sights he squeezed the trigger.’ With these words Pauline Cutting opens her fine account* of the eighteen months she spent as a surgeon at the camp. Bilal was found to be paralysed from the waist down: he is one of two boys who were taken for treatment to Stoke Mandeville hospital in England, and with whom I am about to return to Beirut. Reading Pauline’s book has been no easy task for me, bringing back as it does an experience I shared with her, an experience both bitter and sweet which I would in many ways be glad to forget. But how could I do so?

Medical Aid for Palestinians now has 12 volunteer workers dispersed all over war-torn Lebanon. I shall be taking Bilal and Samir back to broken homes without water and electricity, to a blue sky from which bombs and shells may fall without warning. The treatment of the boys at Stoke Mandeville has been made possible by the generosity of the British public. For these boys it has been a happy few months – a respite from the nightmare of war and the squalor of the refugee camps.

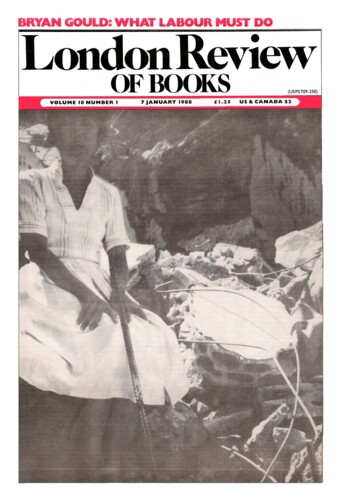

Thirteen years of war has reduced Lebanon to rubble. Broken building upon broken building, ruin upon ruin, many of them dating back to the first civil war of the Seventies. Checkpoints manned by so many different militias that even the locals forget which areas are controlled by whom. The currency continues to collapse and the impact of war is increased by the worsening poverty. Each time I go back, the city looks a little more devastated. But it is still there. It is still the ‘pearl’ of the Middle East, but a pearl tarnished by waves of destruction. For those of us who survived the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and the Sabra and Chatila massacres, the plight of the Palestinians and the needs of the Lebanese poor were to remain with us, thousands of miles away. We could still hear and feel the wounds of these people. We tried to help by launching a British charity, and Medical Aid for Palestinians came into being in 1984. This programme sponsored Pauline Cutting, Susan Wighton and the rest of the volunteers from nine nations whose efforts are commemorated in this book.

The decision to send medical volunteers to work in these conditions was a difficult one. It would have been so much simpler just to raise the money and dispatch equipment. British passport-holders are still kidnap targets in Lebanon, and those who work in the camps are of course exposed to the possibility of a violent death at any moment, and to starvation through military blockade. I remember the board meeting of May 1985, when the news broke of the first ‘camp war’. There were nine votes against my going back to the camps and two in favour – from the vice-chairman of the charity and myself. To this day, I have difficulty in understanding why volunteers keep coming forward. A staff-nurse and midwife, enlisted to deal with volunteers, went out with me in the first British team of 1985 – and she herself narrowly escaped death when a bullet passed two inches from her head. Meanwhile a Norwegian colleague had his elbow shot off. In July 1987 I was returning with a new team of volunteers when the manager of a Cyprus hotel recognised me and shook his head: ‘Doctor, you are not going back to Lebanon, are you? You are a big criminal. You know they are all crazy in Lebanon.’ ‘I know that,’ I said. ‘But we are crazy too.’

Behind all this irrational risk-taking lies a truth that may only be apparent to those who have been there. Most of us are driven to desperation by the sufferings of the people in Lebanon. This is why we keep going back, often under very difficult and dangerous circumstances. Other medically-qualified people who haven’t been there before insist on coming along with us, sometimes offering even to pay their own expenses. The response among laymen, too, has been remarkable. I once received fifty pounds from an Englishman who had never met a Palestinian in his life: that fifty pounds represented his entire dole money for two weeks. I would be a real criminal if I tried to stifle that kind of generosity.

At the beginning of last year the camps were again under siege. Bullets had left many dead or maimed. Rats, surviving on unattended garbage, were being eaten in their turn by starving women and children. When all the grass, dogs and cats were eaten up, women left the camps to buy food and were sniped at. Trapped in Haifa Hospital in Bourj al Barajneh were 40 Palestinian medical staff, doctors and nurses, and four foreign medical volunteers – doing the impossible job of looking after the sick and injured without medicine, water or electricity. Pauline Cutting was among the volunteers and it was thanks to her that the rest of the world discovered what was going on. For me it brought back the horrors of 1982 when Sabra and Chatila were surrounded by tanks, and there was no escape. We called for help, but hundreds had lost their lives by the time help came. It was only when I was taken out of Gaza Hospital with the rest of the foreign medical team that I learnt the painful truth: while we were spending hours and hours trying to save a handful of lives, hundreds of defenceless women, old men and children were being slaughtered outside. Some of us who survived the horrors of 1982 returned to Britain to launch Medical Aid for Palestinians. Meanwhile the Palestinians in the refugee camps of Lebanon once again started rebuilding their shattered homes. But before the war wounds of 1982 were allowed to heal, new ones were inflicted. Between 1985 and 1987, the camps of Sabra, Chatila and Bourj al Barajneh were attacked and besieged four times. A more striking way of putting it would be to say that for the past two years, there were only two months when the camps were not under fire.

In 1987, at the height of the siege, the people of Chatila were granted religious permission to eat corpses if the only alternative was starvation. If we die this way,’ they told the world, ‘let it go down in human history that the conscience of the 20th century has allowed this to happen.’ Moreover, each of the families provided one able-bodied member who would of his own free will starve to death so that whatever food was left could be given to the wounded and the women and children.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.