The well-known speech in Dryden’s play Aurungzebe beginning, ‘When I consider life, ’tis all a cheat,’ has the emperor gloomily observing that we still expect from the last dregs of life ‘what the first sprightly running could not give’. The empress, however, takes a different line: keeping going is what matters.

Each day’s a mistress, unenjoyed before:

Like travellers, we’re pleased with seeing more.

The metaphors are instructive, contrasting as they do the disillusion of the sedentary, who wait in one place for what life may bring them, and the instinct of the migrant to get somewhere, anywhere, on his own feet.

Bruce Chatwin’s latest book is about the idea of being a nomad. From his experiences in Australia he builds a case for fairly aimless wandering about, over large distances, as the way of existing most suited to human consciousness. Travelling of this sort, once a necessity for food-gathering, can now only be done very artificially, when it constitutes a way of life summed up at the end of Philip Larkin’s sardonic poem as ‘reprehensibly perfect’. The natural thing today is to travel as if sitting in a room, an aeroplane or a car. Instant arrival leaves us sitting in another room, waiting for more drops, sprightly or otherwise, from the state’s life-expectation machine. That may be a cheat, but at least it seems to most of us the natural cheat. It takes care of our restlessness no more but no less effectively than migration on foot would do.

Although as an artist he is a black pessimist about the nature of existence, Bruce Chatwin would probably not agree. Like the Empress Nourmahal, he has always been in favour of pressing onward, even though it gives him little pleasure. Larkin himself would have approved his passively meticulous sense of place, and indeed Larkin was a passionate admirer of his three earlier books, particularly In Patagonia. It is a travel book like no other, by far the most interesting recent example of the genre. Its writing reverses our expectations, setting us down at the end of an outlandish continent in a place which seems stalely familiar, but that is no doubt the proper reward of travel, and to the true traveller – still more to his reader – it can be made a satisfying one. Just as compulsively memorable, or more so, this book takes us to the Australian Outback, the central and northern territories. They are, of course, awful – like a lay-by on Western Avenue frequented by gypsies and tinkers.

But Chatwin’s notion was to get to know the lore of the ‘songlines’ or ‘dreaming-tracks’ which run invisibly all over Australia, and which the Aborigines used and use in their endless wanderings-about. These rather sloppy-sounding phrases are presumably renderings from an Aboriginal language, which saw the recognition tracks as bound up with tribal and personal identity, a repetitiveness of the sacred, a way of feeling in past and present, of being both dead and alive. They also involved a complex system of land tenure, based, not on blocks of tribal or personal property, but on an interlocking network of ‘ways through’. What the white men saw as the meaningless habit of ‘Walkabout’ was a kind of bush-telegraph stock-exchange, spreading news of commodities and availability among peoples who never saw each other, and might even be unaware of each other’s existence. Since goods were potentially malign, they would work against their possessors unless they were kept in perpetual motion. Nor did they have to be edible, or useful: people liked to circulate useless things, like their own dried umbilical cords, or a shell that might have travelled from hand to hand from the Timor Sea to the Bight.

Chatwin is uncannily good at conveying the sense in which the transmission of such matters into English, for the benefit of anthropologists and the kind of nuts who get enthusiastic about them, takes away their meaning by making them sound interesting and mysterious. But poetry is what gets left out in translation. His informants seem to have been rather like the lizards who leave their tail in the captor’s hand and wriggle off to grow a new one. Chatwin was told about the ceremonial centres where men of different tribes would gather. ‘ “For what you call corroborees?” “You call them corroborees,’ he said. “We don’t.” ’ By describing one’s life and beliefs, one not only falsifies them but creates a picture of unreality, which may seem all the more seductively comprehensible to others. Margaret Mead was taken for a ride by the New Guineans because she wanted them to be the only way they could describe themselves. No one could be less like Raymond Chandler’s schoolmarm at the snake dances than Chatwin. He makes no comparison or comment, and draws no conclusions: but his reader has the impression that anthropologists can’t do other than mislead, just as the early explorers and artists did, though in a different and perhaps a more deadening way. Chatwin seems aware of doing it himself, and that gives a kind of wry and secret satire to his most hypnotically vivid conversations and encounters. These are the real point of his book, as they were of In Patagonia. So overwhelmingly actual is the writing, in its power of putting places and moments before us, that questions relating to theory and ‘Society’ seem left awkwardly behind. They are there, none the less, making their point all the more effectively for being pushed aside by what, quite simply, goes on, as it does anywhere. The author meets a young Australian working in the Land Rights movement called Arkady, whose father was a Ukrainian Cossack displaced between Germans and Russians in the last war. Miraculously saved from both, he ended up in Australia, but always pined for his homeland, which he once contrived to revisit. His sons are wholly Australian. In a pub up north, Arkady and the author meet a policeman who has thought of a marvellous title for a bestseller, to rival Killer’s Pay-Off, Shark City or The Day of the Dog. Convinced he can sell it for 50,000 US dollars, he is reluctant to impart it to the author except on a basis of literary partnership, but eventually does so, closing his eyes in ecstasy. It is Body Bag. Sleeping Abos are not infrequently pulverised, it seems, by the trucks of the huge road-trains from Alice to Darwin. I should have thought it an excellent title, though Chatwin did not. Meanwhile Aboriginals in the bar are listening to a big white man who has fought in France and married a girl from Leicester.

He had heard we were surveying sacred sites.

‘Know the best thing to do with a sacred site?’he drawled.

‘What?’

‘Dynamite!’

He grinned and raised his glass to the Aboriginals. The birthmark oscillated as he drank.

One of the Aboriginals, a very thin hill-billy type with a frenzy of matted hair, leaned both elbows on the counter, and listened.

‘Sacred sites!’ the big man leered. ‘If all what them says was sacred sites there’d be three hundred bloody billion sacred sites in Australia.’

‘Not far wrong, mate!’ called the thin Aboriginal.

Arkady and the policeman are meanwhile discussing the drinking laws, and the policeman is saying how much he likes Aboriginals, who are none the less standing in the way of progress. ‘You’re helping them destroy white Australia.’ Arkady says he thinks the surest way of judging a man’s intelligence is his ability to handle words.

Many Aboriginals, he said, by our standards would rank as linguistic geniuses. The difference was one of outlook. The whites were forever changing the world to fit their doubtful vision of the future. The Aboriginals put all their mental energies into keeping the world the way it was. In what way was that inferior?

The policeman’s mouth shot downwards.

‘You’re not Australian,’ he said to Arkady.

‘I bloody am Australian.’

‘No, you’re not. I can tell you’re not Australian.’

‘I was born in Australia.’

‘That doesn’t make you Australian,’ he taunted. ‘My people have lived in Australia for five generations. So where was your father born?’

Arkady paused, and with quiet dignity answered, ‘My father was born in Russia.’

‘Hey!’ the policeman tightened his forelip and turned to the big man. What did I tell you, Bert? A Pom and a Com!’

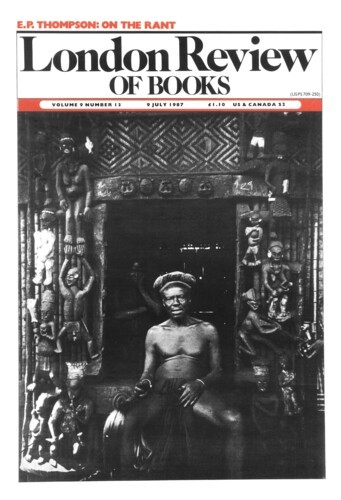

That well-known artistic Pom, William Blake, did an engraving of ‘A Family of New South Wales’ which is reproduced on the cover of Chatwin’s book. In a touchingly direct way it expresses the old ecstatic unrealities which anthropologists have since been adding to with all the devices of scientific ‘objectivity’. Blake must have been told something about Aboriginal style and equipment, perhaps by the authors of An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson, in which his picture appeared. But the faces of his naked family – father, mother, two children – have the ideal look, not so much of the Noble Savage who was a cliché in cultivated circles at the time, as of a contemporary SDP family, or the grouped models in colour-supplement advertising. It is a striking picture, all the same, full of the ‘wiry bounding line’ which the artist sought for. But it is a product of the need to imagine something different from ourselves: ourselves as we might be if we could only live differently. Blake’s near-contemporary Dr Johnson, whom he so much abominated, was inclined to take a deterministic view of human lifestyles. When we can get something ‘better’, we do – not because it makes us happier but because it represents current possibility. An Aboriginal wants an old car, to drive if possible but if not to live under, as a kind of ‘humpy’. Those who persist in following the old ways now find themselves living the artificial life, becoming ‘reprehensibly perfect’, like Blake’s imagined New South Wales family. As birds and animals have no objection to squalid surroundings, the modern Aboriginal lives in a mess of plastic bags, rusty cars, candy-bar wrappings, which presumably become part of his Songlines. His wish to keep or to revive the old ways seems to be mainly a way of getting at the Government, inhibiting land development and upping the welfare cheque.

The poetry of Chatwin’s remarkable pages flitters quietly about among these matters, steering a course, as it were, between William Blake and Dr Johnson. He is particularly skilful with his own version of that time-honoured literary ploy, the most unforgettable character. We meet briefly – and the wiry prose makes them unforgettable – a discontented septuagenarian acting out an Australian image in the solitude of the bush; an Irish priest living in a tent on a sand dune by the Timor Sea, and getting so fond of his hermitage that he has decided to leave and look after derelicts in Sydney; an Abo ‘hunter’ who skilfully chases kangaroos through the spinifex in an old jalopy, and knocks them down. This last treats the author as his slave, forcing him to make pits with a digging stick to change a wheel, and to hold his cigarette as he fumbles with the carburettor. These people are an aspect of journeying, as in immortal books like Evelyn Waugh’s Ninety-Two Days, or Peter Fleming’s News from Tartary.

Bruce Chatwin’s narrative is divided by pauses for quotation and reflection. He has more than a touch of Rimbaud in him, and indeed he quotes from Une Saison en Enfer: ‘For a long time I prided myself I would possess every possible country.’ He reminisces here about the nomads he once met in the Sahel, and about the customs of Mauritania. A waiter in a Timbuktu hotel gave him the menu and said: ‘We eat at eight.’ This turned out to mean that the staff ate at eight, the guests at seven or at ten; and, dropping his voice, the waiter intimated that seven was the better time, ‘because we eat up all the food’. We hear of a meeting with Konrad Lorenz in Austria and Chatwin must have thought of him when he suggested to some elderly Aboriginals that their songs were territorial, like those of birds, and they gravely agreed. Every quick glimpse, everything related here, is in a sense an anti-traveller’s tale, a brilliant focus from the reverse end of that hoary old convention. As in Julian Barnes’s Flaubert’s Parrot, one discovery contradicts another, each aperçu wipes out the one before. We read that ‘by spending his whole life walking and singing his ancestor’s songline a man becomes the track, the ancestor and the song,’ and this at least seems satisfyingly familiar. We recall the bowler and the bat, the leaf, the blossom and the bole. But with a shrug the author leaves the idea, like the lizard its tail, and quotes from the Chinese Book of Odes: ‘Useless to ask a wandering man advice on the construction of a house.’ He says that ‘after reading this text I realised the absurdity of trying to write a book on nomads.’

Whatever it is about, the book is a masterpiece. Very briefly the author meets a young Australian teacher from Adelaide who could in one sense be an alter ego. Graham has gone native, like many young Australians who work in Aboriginal settlements. He found the boys of the Pintupi tribe were born musicians, and so founded his own rock band, making songs with names like ‘The Ballad of Barrow Creek’ and ‘Grandfather’s Country’, which became the song of the Out-Station Movement and number two in the Sydney charts. The band were about to take off for a Sydney visit at a time when they were supposed to undergo their tribal initiation ceremonies, and the elders were very angry. Nothing was sorted out, of course, a depressing impasse remaining which was not helped by young Graham wanting to be initiated too, and telling the senior woman teacher that he refused to teach in a school run by ‘racists’. ‘The education programme,’ he told her, ‘was systematically trying to destroy Aboriginal culture, and to rope them into the market system. What Aboriginals needed was land, land and more land – where no unauthorised European would ever set foot.’ She very sensibly pointed out that the South Africans had a name for the line he was taking: they called it Apartheid.

The author leaves Graham in limbo on the road as he leaves everything else. But the process is neither callous nor reluctant: we sense in some way that the author’s troubles, about which no word is uttered, are metamorphosed into those of the people he meets. Arkady has, in fact, bought him a paperback of Ovid’s Metamorphoses at the Desert Bookshop in Alice. That legendary process, metamorphosis, is, as Ovid’s stories show, as unsatisfactory as every other in living, but it takes care of the next stage of the journey. Solvitur ambulando, as the ancients used to say. A baby will cease to cry if it is walked about.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.