On 18 December 1981, Tirana Radio announced that Albania’s long-time premier Mehmet Shehu had committed suicide the previous night ‘in a moment of nervous crisis’. Although suicide is generally frowned on in the Communist countries – who, after all, could possibly wish to depart from paradise? – the radio referred to Shehu as ‘comrade’ and gave him his full ritual titles. Nearly one year later Albania’s paramount leader, Enver Hoxha, claimed that Shehu had been a multiple foreign agent: of the Gestapo, the SIM (Italian Intelligence), Yugoslavia, the KGB, the USA – and Britain. These allegations were widely greeted with derision as a figment of Hoxha’s paranoia. The credibility of his accusations was hardly enhanced by the fact that he claimed that Shehu had killed himself after being strongly criticised for arranging the betrothal of his son to a woman whose family allegedly contained ‘six to seven war criminals’, and thus attempting to create a scandal which would undermine the Albanian regime. Finally, a few weeks before Hoxha himself died in April 1985, the Albanian party daily said Shehu had been ‘liquidated’ – although a spokesman later denied that this meant executed (given the hyperbole of brutality, such expressions are hard to decode).

Like most other observers, I originally dismissed Hoxha’s accusations as fantasy, and of no interest. Until the mellow tones of a highly conservative former SOE agent in Albania startled me. Out of the blue – I had asked him what he thought of Hoxha – he said: ‘Funnily enough, he never impressed me nearly as much as Mehmet Shehu.’ Further accolades flowed from other SOE men: ‘on the same wavelength as us’; ‘much the best of that bunch of jokers’ (this agent also noted, though, that ‘old Mehmet lost the toss’); and, above all, ‘the only leader who might have been turned or might have been attracted to the West’. My doubts were reinforced when one very shrewd (and very right-wing) old SOE hand asserted confidently that, in spite of Hoxha’s penchant for bumping off his colleagues, there was always a good reason behind the successive purges.

What were the possible ‘good’ reasons? At the time of Shehu’s death speculation centred on three issues: 1. differences over a possible opening to the West in the wake of Albania’s break with China in 1977-78; 2. a policy dispute over the Kosovo, the region of Yugoslavia with a majority ethnic Albanian population where there had been serious riots in spring 1981; 3. the succession to Hoxha (aged 73 in December 1981). None of these seemed enough to explain the break between Hoxha and Shehu: after all, they had weathered many a storm together. Why had their alliance cracked now, after almost four decades of working together? And anyway, what would the point of difference have been? The paean of praise for ‘old Mehmet’ from the SOE agents indicated that a look at the (heavily weeded) files in the Public Records Office might be useful. What had SOE said about Shehu during the war, when its agents were closely involved with him, as they had been with Hoxha?

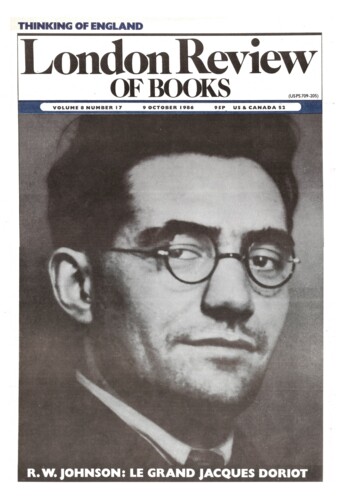

Who was Mehmet Shehu? Born in 1913, the son of a devout Muslim sheikh, he was almost universally portrayed in the published sources as the hard-liner in a very hard-line regime. He had fought in Spain, where he commanded the Fourth Battalion of the Garibaldi International Brigade in the later stages of the Civil War. He spent the years 1939-42 in an internment camp in France, where he joined the Italian Communist Party. On his return to Albania, he rapidly became the main Partisan military commander. He was universally recognised by friend and foe alike as by far the most able Partisan military leader. He led the forces which liberated the capital, Tirana, from the Germans in November 1944. Albania was the only country in Europe, indeed the only country in the world occupied by any of the Axis powers, which freed itself without a foreign army landing on its territory in force.

After the war Shehu became Minister of the Interior, Minister of Defence and Premier (1954-1981). For over three decades he was the second most powerful man in the country. Judgments on him tended to be harsh. One British agent, Colonel David Smiley, wrote that Shehu ‘boasted’ of having personally slit the throats of 70 Italian prisoners during the war. Khrushchev wrote in his memoirs that Tito had told him that Shehu had strangled his predecessor as Minister of the Interior, Koci Xoxe. Khrushchev called Shehu and Hoxha ‘worse than beasts – they’re monsters.’ An article in the US magazine Collier’s at the height of the Cold War in 1951 claimed that Shehu was known in Tirana as ‘the Butcher’ and liked roaming the streets of the capital in disguise. It described him as ‘a tall and spare Hollywood version of a Balkan assassin’. Shehu himself did little to dispel this image. In 1961, at the peak of Albania’s dispute with the USSR, he was reported as telling the Fourth Party Congress: ‘For those who stand in the way of party unity: a spit in the face, a sock in the jaw, and, if necessary, a bullet in the head.’ Hardly a top candidate for Britain’s man in Tirana.

The first thing which emerged from the files I saw was an absence: there was no reference to any acts of cruelty by Shehu. But this could well have been because killing prisoners was universal practice on both sides in the war in Albania. Second, and more important, the British officers closest to Shehu envisaged at the time (mid-1944) a possible future showdown between him and Hoxha. Discussing the possibility of a split in the Communist movement, they wrote: ‘The main personality involved is Mehmet Shehu ... It is hard to say whether there will ever be a showdown [with Hoxha] or not. He is a proud and powerful man, but one with ideals as well ...’ The differences at the time touched on fundamental issues. Right in the middle of the civil war, in July 1944, when Hoxha was going all out to crush his right-wing opponents (the Balli Kombetar and followers of exiled King Zog), the well-informed British officer, Major W.V.G. Smith, who knew Shehu well, reported that ‘Shehu believes possibility of a compromise exists.’ Such an opinion was anathema to Hoxha.

But the British documents go much further than predicting a split between Hoxha and Shehu (which can to some extent be discounted as a standard feature of reports on Communist movements by mainly right-wing agents). A report from SOE HQ in November 1944, just as the Partisans were poised for their final push to oust the Germans and take Tirana, sums up the (alleged) consensus after debriefing 12 British agents just out of Albania, and names Shehu as the repository of British hopes for toppling Hoxha. In a section titled ‘British Influence’, the document claims (most improbably) that ‘the majority of the country have an underlying pro-British outlook and would welcome a British occupation.’ It goes on: ‘there are clearly some who appreciate what Britain has done and who are fundamentally against the present Party policy, but unable to express their views openly ...’ It is ‘important to consider the potential opposition within the Movement and its possible leaders’. The second (of five) names then listed is that of Shehu, described as ‘a personally ambitious and vain man, who has been kept down by the Party for some time. He is undoubtedly the most respected and important military figure within the Movement ... He is a Communist but his personal ambition exceeds his layalty [sic] to the Party.’ The document ends with these words: ‘every effort should be made to prevent the elimination of those pro-British elements already known to us and to endeavour to build these up unobtrusively.’

In itself, this does not prove anything except wishful thinking – wishful thinking demolished in a detailed report a few weeks later by one of the most able SOE agents in Albania, the Hon. Alan Hare (later chairman of Pearson). In a passage discussing the possibility of British support for a revolt against Hoxha, Hare wrote: ‘We are now, for better or for worse, identified with Zogists’ – supporters of King Zog – ‘in Albania, and hated and distrusted by the bulk of the people for that reasons [sic] ...’

This occurs in a section dealing with the FNC – the Partisans – and entitled ‘The Right Wing of the FNC and its Importance’. This discusses three groups who might rise up against Hoxha’s regime. The prime candidate in the third group is Mehmet Shehu, who, Hare thought, would probably try for support from the left, but might try with the Army from the right, which would be his best chance. Such a move would need support from an outside great power – and the only one could be Great Britain. However, Hare goes on to say that such support is quite unlikely – and anyway, any leader who got British backing would be sunk. Britain’s behaviour, he wrote, ‘is making the obtaining of Allied support unpopular with the people, and is considered unsafe by the leaders’. Hare, who is nothing if not a realist, sums up: ‘it is obvious that in the present Balkan political situation, the chances of exerting political influence over Albania by peaceful methods, in the next twenty years, are slender.’

When the British wartime archives were (partially) opened in the 1970s (30 years after the events), the Albanian Government sent one of its top historians to London to go through the files. The result of this research was published in Tirana, in English, in 1981: From the Annals of British Diplomacy: The Anti-Albanian Plans of Great Britain during the Second World War according to Foreign Office Documents of 1939-1944 by Arben Puto. This is a well-researched volume. The notes show that Puto got past the file containing the most damning evidence about Britain’s hopes for Shehu. But Puto does not cite the information about Shehu, or anything else from the file, which contains many other interesting items.

Here the timing is crucial. Puto’s book appeared in 1981. Shehu died in December 1981. In January 1982 Hoxha published his first denunciation of Shehu, citing some official British documents, with more to come later that year.

What seems to have happened is that Puto found the files in which Shehu was portrayed as a ‘pro-British element’. These were dynamite. He had to show them to Hoxha. It cannot have been news to Hoxha that there had been serious policy disputes between himself and Shehu during the war. But seeing documents drawn up by British intelligence agents, some of whom were active in the invasion of Albania in 1949, which list your prime minister as No 2 on a list of ‘pro-British elements’ to be protected and ‘built up unobtrusively’ would have been enough to detonate lethal suspicion in a chronically suspicious mind.

The British documents obviously could not first appear in Puto’s book while Shehu was still Prime Minister. Hoxha apparently sat on the documents until some major policy dispute arose in late 1981, and then used them as the clincher in a showdown with Shehu. Then, as the far-seeing, ever-vigilant leader and chief ‘unmasker’, Hoxha himself published the revelations from Kew.

In post-war Albanian politics, any dispute, whether over internal or external policy, has always been given a foreign dimension (reflecting both traditional Albanian xenophobia and Stalinist practice). All Hoxha’s liquidated colleagues – and they are many – were denounced as agents of some foreign power. Shehu’s polyglot and internationalist past lent itself to the longest chain of alleged foreign masters. Hoxha derided Western and Yugoslav reports that there had been a shoot-out as ‘a scenario modelled on westerns with gunfights which occurred in the saloons at the time!’ – but, of course, this was also the Albanian way of doing things. ‘Old Mehmet’ lost the toss, and got a bullet in the head. Not because he actually was a British agent, but because the British named him as a good man to lead the movement to topple Hoxha – and that was more than enough for Hoxha to decide to bump him off.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.