On Wednesday mornings I fall out of bed in a hurry because I have to clear off to the Labour Exchange to sign on. Check obsessively that I have my key, slam the door, and hurry off. Tear through the park. I love the park – it’s more or less the same as it was when I used to walk through it going to school, years ago. It’s landscaped, but when I’m flying through it to get to the Labour Exchange on time I don’t linger to admire the scenery. Every time I go past the fountain, near where Henry Royce’s statue used to stand, I mutter and tick away to myself: ‘Fkin bastids fkin bastids fkin bastids’. I saw that on a wall once and it seems to express something inchoate and furious. The Council came and took away the statue, which had always been there, and put it outside the Council House.

There’s lots of people signing on, lots of queues. The unemployment rate in the town is 14.4 per cent. In this area it’s 37.7 per cent. I don’t usually speak to anybody. About eighteen months ago there was a big row and discussion in the queue, with everybody chipping in. If I see any of the people that took part we smile and nod and exchange a few words. Otherwise I don’t speak to anybody. There’s nothing to say. On the wall near the door a teenager has scratched: ‘Have I survived school dinners for this?’

When I stay in the house for a long time and don’t see anybody, and then go out again, everybody looks peculiar. It’s nothing to do with age, nationality, looks – its just that all the passing faces look slightly grotesque, and alike in their peculiarity. I move off to Woolworths Cafeteria to meet a girl who signs on ten minutes before me. In an abandoned jokeshop window a sign reads: ‘A Laugh a Day keeps the Crisis at Bay.’ Uh-huh. It’s been there about eight years.

In the evening Chrissy and her small children and I walk about among the ruined houses round the corner, finding plants, just looking. We’ve known each other since we were three, we used to play around these streets, and go down them now remembering people who lived in the houses and talking about what became of them, and things we did long ago. I don’t think there’s anything sadder than seeing the little gardens that people have cared for and tended for years laid desolate and wild, waiting to be bulldozed. As we stand on Rosehill Street with dirty hands and arms full of grubbed-up marigolds and garden poppies, a small solemn procession of men leaves the mosque. I see my ex-landlord, Mohammad, with head ritually shaven and bowed. I don’t wave at him or hoot across the road ‘Hi there, Mohammad,’ because we look thoroughly disreputable, our hair blowing about, legs and shoes dusty, and the children quarrelling.

On Fridays my Giro comes, and a form from the Council saying the rent is going up. This doesn’t affect those on the dole, because Social Security pay the rent directly to the Council – it doesn’t pass through claimants’ hands. On the back of the form is a set of rules about only using the property as a private dwelling, care of dwelling and garden, nuisance to neighbours, including harassment, whether racial or otherwise. The last bit is underlined, which infuriates me. I’m not talking about the clause itself, because I agree with it – but about the fact that somebody has stood in the Housing Department and underlined it, as though we’re all in need of correction and moral guidance, from somebody who almost certainly doesn’t live round here. Well, that just takes the biscuit. What’s it supposed to do, anyway? If you get on with your neighbours, then it’s superfluous, and if you don’t, holding up a stern verbal finger whilst keeping well clear – that’s not likely to make things better.

Hare off round town quickly. Take in a gas instalment. Outside the Gas Board a boy plays an accordion. On the pavement chalk bluebirds fly about, but bikes have been run through them, leaving blue hoops behind. Now comes the real hard part – food shopping. Wandering around among the counters I lose my appetite completely. Over on the meat counter there’s a saddle of lamb for £12.85. I look at this curiosity like it’s in a museum, have absolutely no desire to eat it. Even if I had the money, I wouldn’t spend it on that. If I stayed too long here, I could throw up. Especially when you come out and there on a hoarding is the picture of a bag of bones that should be a baby. Sometimes I wonder if the Third World will ever be allowed to be anything but hungry, while the industrialised countries still have their inner hunger. The image of starvation is maybe too near what people in this country feel like inside.

Coming back from town, I see Mrs Holmes, the lady next door, standing on her doorstep. She shows me her knitting. She’s had migraine badly, so could only manage to cable two-thirds up and knit the rest plain, but it looks fine. She’s lived here for over thirty years, and she’s waiting on the step for her son. He grew up round here and passed lots of exams, and got a good job, and now he comes to see her every day in a big silver car.

The man next door on the other side, Mr Shaw, has been altering their passageway, and putting up pinewood panels. He’s getting on a bit, so only does it now and then, when he feels like it. He showed me last week – it should be quite good. He has made lots of alterations to the house over the years, and it looks bigger inside as a result. The Shaws came from the West Indies a long time ago. Mrs Shaw is blind now. She stays in the house all the time, and not many people in the street have seen her. I’ve only seen her twice – on Sundays getting into the car to go to church.

There’s a fearful banging on the door. It’s Ahmed. He comes straight from the mosque, dumps his cap and book on the mantelpiece and makes for the carrier-bags in the kitchen, scratting about in them. ‘Oooo, chocolate cake.’ ‘You can just come out of there. You’re not having any. Moslems can’t eat chocolate cake, it’s not allowed.’ ‘They can. They can, Carol. That’s what Moslems can eat.’ ‘Oh I see, Mohammad told you, did he, he put it in the Koran: all Moslems must eat chocolate cake on Fridays?’ ‘Yes he did,’ he says, stoutly optimistic. He doesn’t believe for a minute that he won’t get any cake.

Sunday in the garden. It’s very quiet and full of sunshine, and roses flaming orange and red, like a flowery furnace, and clusters of blackberries all along the wall. The whole garden is wild – I just haven’t trimmed it at all, although I did plant a pear tree two years ago, which is still battling to survive. I stand talking to one of the Shaw girls, and she’s telling me about her sister who has plum trees and makes jam. Two of the teenage sisters come out, nod, and one of them says something about wogs, just loud enough for me to hear. They laugh under their breaths together. I’ve never said anything like that to any of them, so I just ignore her, the cheeky little sod.

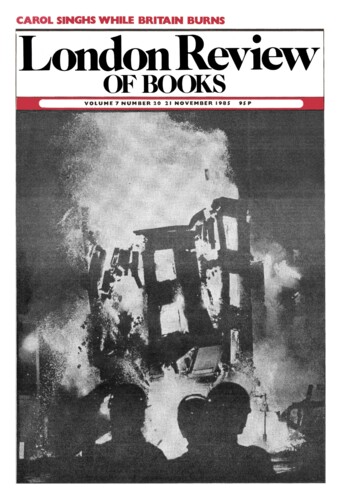

On Monday morning I get up, put on the kettle, light the grill for toast, trip over the cat’s plate, curse, and switch on the wireless, straight into the news. It’s all about Handsworth. Bloody hell. Straight away switch it right down – I don’t know why, I just don’t want any of the neighbours to know I’m listening to it. Late in the morning the house across the way blasts a record out for about three minutes and then there’s silence again. Later Mrs Holmes and Gail and Lakvir come out, all talking.

This sounds awful, I know, but I get fed up hearing rotten news, so don’t always listen. And I’m glad I haven’t got television. Not many people I know watch television much actually, unless they have small children, and then it’s switched on to amuse them. It’s something to do with not being able to sit still and watch other people when you want to get on with your own business. The only time during the news about Handsworth that I regretted not having a television was when that government minister went there and then had to run off. But you can’t have everything, and it was a small treat hearing about it. It was awful about the people who died.

‘Yes, everybody’s dead mad about it,’ says Ahmed. ‘Did you see the rioting on television?’ ‘Yes, I don’t know – some of it. Then my mum got cross and said, “I’m sick of this all the time,” and switched it onto the other side.’

Chrissy doesn’t watch television much either. ‘Yes, it’s terrible,’ she says vaguely. ‘I don’t watch much, I just can’t do with it, it gets on my nerves, and if I watch it for too long I start picking up a code and then I don’t know where I am. I don’t even like to be in the same room when it’s on ... I mean, I have to be so very careful. I know there’s a bug in here.’ She was nursing in the local mental hospital for years, and then she was taken in herself after she had her last baby. When she starts to talk like this, I always look doubtful – I don’t know why, because I sometimes think that myself, although I don’t tell her so. That’s what happens when God drops down out of the sky – you’re left with an ugly little bug. For months, one time, I thought I was being followed round by a red car. Every time I went out there was this same red car. It was even there several times over, and sometimes it had a black roof, but it was the same car, following me. I’d see it parked, turn a corner, and there it was again. It’s easy to say they were all different cars. They were but they weren’t. A boy who used to live in the next bedsitter to mine spent seven months seeing cross-eyes. Every person he looked at appeared to be cross-eyed. ‘I kept rubbing my eyes because I knew it couldn’t be like that. But I couldn’t get rid of it.’ None of this has anything to do with drugs. When I came out of the mental hospital and walked about I’d turn a corner of a street I knew and instead of the well-known street there’d be ruins. This happened so many times that places that were still standing I’d see as ruins. Destruction by mobs round here won’t be any novelty. It’s been happening for years.

Ahmed comes round. It’s Saturday and he’s spent all morning looking for a man who changes the colour of your shoes. He says there’s been a big Sikh procession in Rosehill Street, men with swords on floats. ‘Like May Day, you mean?’ ‘I don’t know. They didn’t look very pleased. They’re still mad about Mrs Gandhi.’ He’s wearing a spell rolled round and sewn into a piece of white linen. It’s a magic word that only the man who wrote it can understand. Ahmed’s mother brought it back from Pakistan, to stop him having bad dreams. ‘And does it work?’ ‘Yes, I think so. When I wear it. I don’t always wear it. Sometimes I like a change.’ He nags to go shopping, in town. I hate shopping. Pass a billboard with its headlines for the local paper DRUG YOUTH FOUND HANGED. In town, where priorities are different, a board advertising the same paper announces LOCAL DJ ACCUSED OF FIDDLING. Drug-taking and glue-sniffing are apparently a big problem round here. Since being at his new school Ahmed’s constant conversation is about drugs.

I hate shopping. There’s nothing in the shops I want. In a shop window there’s a jacket knitted in a tartan design. The idea of knitted tartan amuses and intrigues me. I examine it closely to see how the illusion is achieved. But I have no desire to own it. Stop wanting – an answer to the problem of living on social security? Not really, because if lots of people just looked at things instead of desiring them, then looking would become stealing, and people would be in the wrong for doing it. Sometimes I don’t even want to look at things, as though that’s already the case.

All through Wednesday night I lie in bed hearing police sirens blaring. That’s no surprise, as the local team are playing Leicester. The next day headlines in the local paper announce a full-scale riot, at a local pub. Apparently people were leaving the match while it was going on, to join in the fight.

I stand at the sink washing the pots. About six yards away the friendly Shaw sister picks berries on the wall. We wave to one another enthusiastically, like we’re miles away. In her garden Mrs Holmes stands wondering over her beans. In spite of the lousy summer, Gail’s sweetpeas have fought their way to the top of the wall.

When the news about Brixton comes through, Mr Shaw next door starts banging on the wall, doing his alterations. He hasn’t touched them for weeks. As the evening wears on, he thumps away. At one point it sounds as though he must come through the wall. The newsreels are maybe making him feel energetic. If they keep the rioting going for a bit longer, maybe he’ll finish his hallway. He’s still thundering at twenty to twelve. I hitch up my nightdress, put a skirt on over it, and saunter out to the chip shop.

‘What will Hawa and Teddy be doing – will they be in the riots?’ asks Ahmed. He’s never met them, only heard me speak of them. We all used to be Mohammad’s tenants for four years, but haven’t met for ages. ‘They’ve got a young family now, so I shouldn’t think for one minute they’ll be anywhere but at home.’ I know what Teddy will be doing, though. He’ll be sitting in front of the television chuckling. Appalled, but chuckling. I may be wrong. But you don’t live in the same house with someone for four years and not have some idea of how they will react. I remember one Saturday a couple of years back. When the football crowds passed they went down the street smashing all the windows. All the houses were empty except mine and next door. I wasn’t at all scared, but when night came I did get a bit scared, because I was living alone in two streets of empty houses, with an old lady next door, and now the front windows were out. When I heard thumping at the door my heart sank a little. I looked out from upstairs. It’s Hawa – she’s in carpet slippers and has left her month-old baby to run down four empty streets to come here. Her voice floats up. I peer out at her dark face in the darkness. ‘We heard about your windows, Carol. Teddy says he’ll come and put them in for you.’

Chrissy hates buses, she walks everywhere, she likes to feel the ground under her feet. ‘I don’t like buses, I don’t really feel I’ve gone anywhere.’ Every year when her daughter Paula was small they both walked off to the other side of town, to the only church May Day that was left. ‘Even that’s gone now. And it made a nice day for the children. I used to dress Paula up in a little pale green dress with a wreath of flowers, and we joined the procession.’ There’s a photograph on the wall of six-year-old Paula, with hair-ribbons and bunches, and flower-circlet. It’s only ten years ago. Under all the white chalk Paula dowses on her face you can just see the same little face. ‘She gets her Giro, goes out and crashes it straight away, and then she lies in bed all day reading horror stories, when she’s not running wild with a lot of black girls. And they do get up to some things. They take things from shops and goodness knows what. I’m not talking about, how shall I say? stealing – like, done secret. They just all march into the shop together and take what they like. Quite open. Nobody stops them. It’s terrible. I got this blouse from them, because they sell stuff at backdoors.

Apparently, while the last lot of rioting was going on in Tottenham, round the corner here, at the bottom of the street, thousands of Sikhs converged on the Gurdwara, which has been occupied by supporters of Khalistan. The original more moderate section has got a court order to evict them.

Gail, who works in a pub down there, told me. She wasn’t allowed to go home, had to stay in the pub until the next morning, because the whole area was sealed off by police. ‘There was police there from five different forces, even the Metropolitan. The Sikhs wore orange turbans and they came into the pub with their swords and ripped out the phone. There was absolutely thousands of them. I wasn’t scared. Well, I was a bit when they set fire to something in the middle of the road.’

As she’s talking, I start to wonder if she’s lying about there being thousands of Sikhs just round the corner. It just seems so incredible not to have known. If there’s one thing in the world I value, it’s the capacity to be rational, which used to seem very dull. But if you’re let loose into a series of nightmares you come to value it. I think of Graham, battling to stand on his feet, knowing in his mind that every person couldn’t have cross-eyes, yet still seeing them. And this is quite apart from the problem of drugs, or the problem of racism.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.