In January 1984, two months into an overtime ban, with the spectre of strike hanging over us, if anyone had asked me, ‘If we strike how long will we be out?’ I certainly would not have said eight months. But here we are: 32 weeks on strike, and prepared to do another 32 if need be. Why? Principles. To protect our jobs and, above all, our communities.

On 6 March 1984 Cortonwood Colliery NUM branch officials were told that their colliery would close within five weeks. This despite the fact that only one month earlier they had been told that there was at least five years’ working life at the colliery: a colliery with possibly the finest coking coal in the country, a colliery to which men from nearby Elsecar Main ‘Colly’ had just been transferred after their pit had been closed due to exhaustion. They had been promised a bright future at Cortonwood, but had not even been issued with locker keys for Cortonwood Baths: they were being bussed back to Elsecar to bathe after each shift.

On 10 March a special meeting of all Grimethorpe miners was called to hear, debate and vote on our delegates’ report regarding the closure of Cortonwood and also of Bullcliffe Wood – both within the Barnsley Area. They also heard reports on other pit closures: Herrington in Co. Durham, Polmaise in Scotland and Snowdon, Kent. The voting was unanimous: strike from Monday 12 March. So my colliery was on strike; my village was about to become involved in a dispute which no one envisaged would last this long.

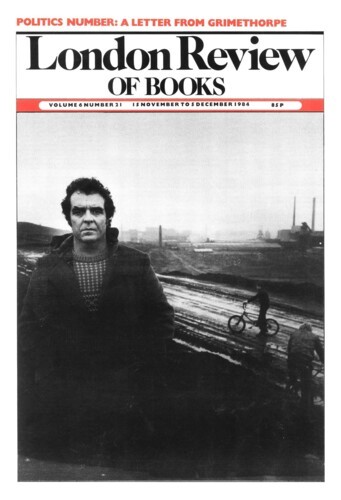

Grimethorpe, a village of about five thousand people, predominantly miners, Grimethorpe miners, miners from other pits in the surrounding district, area workshops, the local NCB power station NUM members – all out, with one purpose in mind, the safeguard of our jobs, our community. My village of Grimethorpe is the home of one of the most famous colliery brass bands in the world and of one of the finest first-aid teams in Great Britain; a happy village, a village of hardworking, moral, principled people; the village where my two sons, both miners, and two daughters were born, and where my wife and I will probably end our days. Grimethorpe, a village always at the forefront if support is needed by any other pit, and one of Yorkshire’s largest collieries. Rumour has it that Grimethorpe is 17th on the closure list. There have been feeble denials by the Board, but rumours have a nasty habit of coming true in this part of the world.

During this 32-week-old strike the Coal Board, along with the Police and various other bodies, have tried to intimidate and demoralise us. To no avail: mainly, I think, because of the support of our wives and daughters, along with women in other parts of the striking coalfields. They have been absolutely marvellous, running kitchens, food parcels, funds, rallies – and even picketing along with their husbands. I think that without their support this strike might have crumbled. Now, after thirty weeks of strike, after thirty weeks of managing on less money than a single man gets on supplementary benefit, thirty weeks of riddling coal for our fires – each bag takes one and a half hours to fill, and we have to have coal because 95 per cent of us have solid-fuel central heating and cooking stoves – after all this we are suddenly confronted on the coal stack by hordes of truncheon-wielding, riot-helmeted police with dogs. Men, women and kids are punched, kicked and arrested for picking coal to cook with and to keep warm. Many of them are left bleeding and bruised.

This happened on 12 October (19 arrests). On Sunday 16 October it happened again: 120 riot-clad police against sixty or seventy people, mainly middle-aged men – most of them with bad chests and unable to run – and women and kids. There were 28 arrests on this occasion.

Monday 17 October was a different story: the Police were confronted by quite a few young men: we were not running away any more. Confrontation took place on the tip – miners versus police. For a brief time we had shown that the people of Grimethorpe had had enough. The police station was stoned, and windows broken. By three in the afternoon the top end of Grimethorpe was sealed off by three hundred riot police; by 11 o’clock nearly six hundred riot police were running amok in the village, clubbing anyone within arm’s reach. The next day, Tuesday 18 October, people in the village were running a gauntlet of foul-mouthed obscenities, mainly levelled at women and young girls, from police officers still clad in riot gear.

I make no apologies or excuses for the actions of myself or my fellow miners here in Grimethorpe, for what happened. As I said at a public meeting on Wednesday 19 October, husbands, brothers, fathers and sons have been killed at Grimethorpe Colliery. This village has had its share, if that is the word, of fatalities; men have paid for the coal lying on the coal tips with their blood, and morally the coal is ours. And we will win, through principle, determination, guts. We will obtain an honest and just victory.

Grimethorpe has now returned to its former way of life. But, with a few exceptions, the determination to stay out till we win has grown; the number of volunteers for picket duty has grown; and so has the support and good will of trade-unionists all over the country. We in this close-knit community have been bonded closer together by the antistrike tactics of the Police and the Coal Board.

On the lighter side, the art of making wine for 20p a pint and beer and lager for 10p a pint has reached professional standards. Jumble sales of nearly new clothing, footwear, baby napkins and food are held regularly. Pea and pie suppers with free lager and beer thrown in – all you can eat and drink for a pound – happen nearly every week. They help to keep morale high and to swell the funds of the women’s support group parcels fund which, every week, distributes a hundred or more food parcels to the needy.

The Police and NCB management have accused us of intimidation, of bullying threats. But there have never been more than four pickets at Grimethorpe colliery’s front gate, because loyalty to our cause, to the union and to the leadership is second to none. This fight is not only for Grimethorpe colliery and its community, but for other pits and communities throughout the country. It is not only for miners, but for other workers too, and for the right, fought for by our forefathers, to belong to a trade union.

Since the trouble in Grimethorpe, the removal of coal from the coal tip, temporarily stopped by the NUM, has started again, but on a reduced basis: it goes only to the local carbonising plant, Coalite Supply Smokeless Fuel, and to old-age pensioners, schools and hospitals. The picking of coal by striking miners is non-existent because of the continuous Police presence. Would-be pickers are dissuaded by various methods – police dogs off the lead supposedly being exercised are not the least of these. There are also constant police patrols, NCB security patrols. Video cameras fitted with intensifiers for use in the dark have been installed on the winding headgear. Resentment of the Police presence on the tip is voiced by the strikers every day. To them, it is oppression, and, although a lifetime in a mining village limits your knowledge of oppression, retaliation seems instinctive. The brutality of the riot police drafted in from Southern counties has left deep scars on the minds of the people of this village, and an inheritance of hatred and mistrust of the local police. This hatred will take until long after this strike is over to heal – not months, but generations. The contempt which the Government and the upper echelons of NCB management have for the miners has never been so blatant as during this trouble. Many miners still remember the bad old days – private ownership, low wages and the absence of safety precautions – and we will never accept these conditions again. Meanwhile the only weapon we hold is the withdrawal of our labour and the determination to secure a just and lasting victory.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.