Immediately I saw the title on the jacket of this book I remembered with the unfailing affection of an old man for past events of no apparent relevance to anybody else that I was once made a freeman of the city of Memphis in, I think, Tennessee – not Egypt. It happened because the local political boss that year was of Irish descent. He even presented me in public with a key to the city – that is to say, a three-quarter inch replica in painted gold, which I at once passed on to the next pretty young woman I met to hang on her charm bracelet. The relevant correlative? A little ethnic gesture to catch another little ethnic vote. In a word, politics.

What I now sardonically call my memory flew next to a neighbouring State where another gentleman of Irish origin initiated me as a member of the Ancient Order of Kentucky Colonels, at the same time presenting me with a poem by a local man bearing the dactyllian Joycean name of J. Hilary Mulligan. Of this poem I can quote one verse:

Songbirds are sweetest in Kentucky,

Thoroughbreds are fleetest in Kentucky,

The mountains tower proudest,

Thunder peals the loudest,

The landscape is the grandest

And politics are the damnedest In Kentucky.

Was I, I asked myself, glancing again at the unopened book before me, so very wrong in thinking that these two trivia suggest the only sort of politics likely to have appealed to the most heroic figure in Irish life and literature since Charles Stewart Parnell: politics, that is, proposing a parade of rascality, hilarity, treachery, hypocrisy, audacity, idealism, always shot through by moments of splendid courage and always ending in bitter tears? If Dear Reader will allow me to vanish for three minutes during which I beg the silence that every half-decent Irishman begs at least six times in his life when he hears again the funeral bell tolling for The Lost Leader, to which I would add another three minutes for consideration of the biographico-literary question I have just posed to both of us, I think I can formulate a more or less final decision about politics and Joyce.

The three minutes are up. It is all a matter of definition. If the sort of politics I have been referring to did interest Joyce, then we at once understand their relevance to the man’s bent, character, genius, spirit – call it what one wills – that is, we can have at least some idea of the magical process whereby this sort of ‘politics’ enriched his Human Comedy in the hilarious Cyclops chapter of Ulysses, with its brawling but never boring comic character called ‘The Citizen’, and how they deepened the Human Tragedy of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man with that painful scene where the family battles passionately over Parnell. But if that possessive apostrophe in the book’s title means that Joyce was nourished in his work by knowing le dessous des cartes of politics as the science of governing a country or managing a community, then even his most devoted and admiring readers (among whom I ardently reckon myself) are going to find it hard to reconcile this sort of social-minded, institution-oriented writer with the impression most of us have gathered from his life and writings of a passionate, poetic loner, virtually an élitist, withdrawn, a sceptical, ironical exile who never joined anything larger than a dinner party in a first-class Parisian restaurant.

So then, it is not only a question of the definition of the word ‘politics’ but a redefinition of the writer and the man. Perhaps Dominic Manganiello has demonstrated this kind of formative interplay in Joyce’s mind between the art of government and the art of literature? Perhaps he has shown us how irredeemably different A Portrait or Ulysses would have been without their author’s study of, say, Irredentism, Nationalism, Socialism, Anarchism, Bakunin, Ferrero, Marx? The idea is so exciting that I decide to take a refresher look at A Portrait.

I am a little taken aback to find that it is some 64 years since the book was published in the United States of America. (No British publisher cared to risk it. In the words of one of the best editors of the time, Edward Garnett, it contained ugly words, ugly things, would be considered a little sordid; he did have words of praise for it but thought the whole thing needed to be rewritten.) That was 1916. I am further taken aback to find that I did not get around to it for nine years, but I remember that for some time after 1916 we stay-at-home Irish were otherwise preoccupied. I have never read it since, as a whole, for two reasons: the fear that a rereading might deprive me of the memory of that first exquisite experience; and the fear that I might become dominated by the influence of so powerful a personality. Did not Auden once tell young poets to begin by modelling themselves on some established poet, but not one of the first class lest he affect them hypnotically, adding that he had done this himself, carefully choosing the minor poet, Thomas Hardy? Would Dear Reader bear with me while I retire to reread A Portrait now? I shall not delay him more than two seconds, as when one reads a cassette letter from a friend whereon he says he must halt now for lunch and resumes after two seconds with: ‘Now that I have had my lunch ...’

I have found A Portrait just as seductive as it was on that first reading more than half a century ago – chiefly, I now think, because this young man had the immense arrogance of his own softness, unlike those hairy chests of a later generation who had only the courage of their own toughness, but also because his nature, therefore his language, was such an unwonted blend of needle-sharp naturalism and the wooziest poetic suggestiveness. Certainly, never was a revolt – and this novel, like all his work, is the chronicle and commentary of a Miltonic revolt – expressed so tenderly. Indeed, at times one fears that he is going to break into a glutinous prose version of Dowson’s ‘Cynara’ – always remembering that ‘Cynara’ is a far better poem than Willy Yeats had written by that time, and that Eliot considered that it brought a new rhythm into English verse. Who can ever forget their first throat-gulping reaction to the scene where Stephen at last decides to reject the disciplines of church and state for the free life of the artist? Young Dedalus, who has, under the temptation to become a priest, been mortifying his flesh for a long period of doubt and torment, here gives himself up one afternoon to the wide vacancy of Dollymount Strand on the northern side of Dublin Bay, alone, unheeded, happy for the moment, ‘near to the wild heart of life’.

He was alone and young and wilful and wild-hearted, alone amid a waste of wild air and brackish waters and the seaharvest of shells and tangle and veiled grey sunlight ... A girl stood before him in midstream: alone and still, gazing out to sea. She seemed like one whom magic had changed into the likeness of a strange and beautiful seabird. Her long slender bare legs were delicate as a crane’s and pure save where an emerald trail of seaweed had fashioned itself as a sign upon the flesh. Her thighs, fuller and softhued as ivory, were bared almost to the hips where the while fringes of her drawers were like feathering of soft white down ... Her bosom was as a bird’s, soft and slight, slight and soft as the breast of some dark-plumaged dove. But her long fair hair was girlish: and girlish, and touched with the wonder of mortal beauty, her face.

She was alone and still, gazing out to sea; and when she felt his presence and the worship of his eyes her eyes turned to him in quiet sufferance of his gaze, without shame or wantonness. Long, long she suffered his gaze and then quietly withdrew her eyes from his and bent them towards the stream, gently stirring the water with her foot hither and thither ...

– Heavenly God! cried Stephen’s soul, in an outburst of profane joy ...

Her image had passed into his soul for ever, and no word had broken the holy silence of his ecstasy. Her eyes had called him and his soul had leaped at the call. To live, to err, to fall, to triumph, to recreate life out of life!

Fin de siècle? Like his embarrassing poems? What risks he took, and barely conquered! Veille de siècle? No. That for certain. ‘We were the last romantics,’ Yeats might haughtily say of his own generation, though, to his immense credit, acknowledging that Homer’s ‘high horse riderless’ could be ridden also by a different kind of Ulysses – dreamy, subjective, bawdy, brainy, Baudelairian, magically blending ‘traditional sanctity and loveliness’ with wine-dark sin, golden ordure, common life, the crudest facts, a melancholy as exquisite as his own and laughter galore. For while the twilit scene that we have just read takes as its emblem a vision of virginity, we will remember that the whole of the three-chapter adagio which it concludes had begun with a very different dusk. ‘It would be a gloomy, secret night. The whores would be just coming out of their houses yawning lazily after their sleep. He would pass by them calmly waiting for a sudden call to his sin-loving soul from their soft perfumed flesh.’ It was a large element in Joyce’s art thus to blend Defoe and Blake. (See page 329 of Ellmann’s incomparable if, one must always watch for it, slightly uncritical biography.) It was the way, too, of another Irish poet whom Joyce could respect, James Clarence Mangan, ‘taking into the vital centre of his life “the life that surrounds it, flinging it abroad again amid planetary music” ’.

But where have we left Politics? One can anticipate the answer, pat if not strident. ‘You have said it, the whole thing is a supremely political statement, a revolt into exile, a changing of one country for another.’ Is this true also of Yeats’s ‘supremely political statement’ when he saw a toy fountain in a chemist’s shop-window in London and announced that he would arise and go now and go to Innisfree? Obviously in this game it is vital to have definitions, distinctions, and above all close connections between outer event and inner effect. Otherwise by making the words ‘political’ and ‘politics’ mean everything we make them mean nothing.

It is a trap into which, now that I am reading Professor Manganiello, I find this book stumbling more often than one would have expected of a doctoral thesis. There are no doubt various explanations for this, but one in particular is recognisable: that insatiable thirst for completeness which betrays so many scholars into a surfeit, until what begins as a worthy project slips imperceptibly into a wordy one, and the more wordy the less reliable.

Here is a small example of what I mean, from page 15 of Joyce’s Politics. We are told that ‘at the earliest stage of development’, Stephen’s mind is exposed to ‘the Irish world of politics’ in the form of Dante’s two brushes representing Michael Davitt and Parnell. If this sentence refers to a child of three or four it sounds more than a little over-charged. But the next sentence has an even more momentous air: ‘As he grows older and the scene shifts to Clongowes Wood College Stephen is seen meditating on the story of Hamilton Rowan.’ (Rowan was an 18th-century patriot.) With this sentence out guide is in difficulties. We may allow a child and an old lady to give pet-names to two brushes. It is another thing to be told that ‘as he grows older’ he ‘meditates’ on actual historical events. We become sceptical. A novel is not a biography. Dedalus is not Joyce. We ask ourselves at what age did James Joyce become history-conscious? The novel does not say. Manganiello does not say. But we do know that Joyce, if not Dedalus, went to that school when aged six and left it aged nine. In what circumstances did this precocious meditation occur? When we check with the novel we find that the little fellow paused in what seems like a rough-and-tumble football practice, noted with a shiver that the sky had become pale and cold, looked longingly at the lights of the college and – here comes the ‘meditation’ – ‘wondered from what window Hamilton Rowan had thrown his hat on the haha’. The scholar in his understandable eagerness not to miss a trick has made much ado about little or nothing. The example is, indeed, trivial, but it illustrates a danger that too often mars an over-conscientious book.

It would be tedious to give many other examples of near-irrelevance, but I cannot resist the 20-page chapter chiefly devoted to the Neapolitan journalist-historian Guglielmo Ferrero whose works L’Europa Giovane and a five-volume Grandezza e Decadenza di Roma, though looked down on by real historians like Benedetto Croce, attracted Joyce’s attention during his decade in triste Trieste. In the first book, we are informed, Ferrero maintained that Italians make better cakes than the English but that English biscuits are works of art. The relevance of this to the subject of the book is that Joyce spent his last two lire to test the veracity of the statement. His decision does not transpire. To be sure, the chapter deals with other Ferreroisms that may or may not have pleased Joyce, who, for example, would ‘probably’ have agreed that Parnell was calculating but ‘did not consider him a fanatic’, or who in reading Ferrero’s vast work on the greatness and decadence of Rome. ‘probably all of it’, ‘probably’ realised for the first time ‘that Horace’s involvement in his age was in some way similar to his own task as a novelist in relation to Irish society.’

Some of the Joyceian connections would seem to be unconnected with politics, such as that Ferrero’s descriptions of Scandinavian cities made Joyce write to his brother that he longed to visit Denmark. Where we do come on what deserves to be saluted us a firm connection between what Joyce read and what he wrote is when Professor Manganiello points to a reference by Ferrero to an incident in The Three Musketeers that inspired Joyce to write his short story ‘Two Gallants’. The fact that Richard Ellmann recorded this connection years ago is of interest only because he cautiously disposed of it in a six-line footnote whereas the later scholar insists on introducing the matter with the portentous statement that ‘Joyce was able to mould some of Ferrero’s political ideas into fiction,’ and then takes off about German militarism, sexual brutality, ‘the debasement of love as a signal of a national temperament’, with a footnote involving Siegfried, Helen of Troy and the Scandinavian as (Ferrero loquitur) the father of the modern Englishman ‘who is indifferent to love’, all being parallels to ‘England’s equally brutal conquest of Ireland’.

Less cautiously than Richard Ellmann, and I hope not too grumpily, I refuse to believe that anybody evet wrote, composed, painted anything through inspiration. What is so grumpifying about the idea is that it over-simplifies a complex activity with a journalistic catchword. Ultimately art is magic, the artist an alchemist, his success inexplicable. Unfortunately few critics believe in magic; they believe they can reveal the father and mother of every hue, eyebrow, limb of every child of art. Like that chemist’s window in London that ‘inspired’ Innisfree. More disastrously, they forget that the artist keeps changing all the time: the Joyce who browsed one week with Ferrero in Trieste was not the Joyce who relived his old Dublin days the week after with his two gallants. He has himself insisted on this, and on the fact that the thinking, remembering, considering part of himself, which is the only part of any artist that biographical huntsmen can smell out, has to die before pen touches paper. He says it in Ulysses (in my battered 1937 edition, on page 183) through the persona of young Dedalus when showing off his Shakespearian knowledge to his sceptical or admiring listeners in the National Library to prove that the ghost of Hamlet’s father is his own son:

– As we, or Mother Dana, weave and unweave our bodies, Stephen said, from day to day so does the artist weave and unweave his image. As the mole on my right breast is where it was when I Was born, though all my body has been woven of new stuff time after time, so through the ghost of the unquiet father the unliving son looks forth. In the intense instant of imagination when the mind, Shelley says, is a fading coal, that which I was is that which I am, and that which in possibility I may come to be.

Meaning that no scholar can ever tell what has become or may become of any writer’s recorded experiences by the time the mind of the artist has become a faded coal and his imagination of the event is in flame. Eliot said it more simply when he compared the poet’s mind to the shred of platinum that, unchanged itself, transmutes the artist’s experiences, emotions, passions, feelings into imaginative art. So, Joyce may or not have debated Socialism with his brother (Manganiello says ‘strenuously’, Ellmann says ‘tortuously’), or Anarchism, or Irredentism, or Nationalism, but as a writer he simply exploits everything, achieves Eliotian impersonality, feels with passion, exiles himself, makes use of the double feeling of possession and alienation to remember what he needs to remember and forget the rest, to forget even what he started out to write, to be unable even to understand what he has written. A friend once said to Joyce that she liked The Waste Land: ‘But I couldn’t understand it.’ Joyce retorted: ‘Do you have to understand?’

Joyce had all the interest in politics that a mouse might have in mousetraps. His curiosity about politics was really not much more than the concerned inquisitiveness of an outlaw. The best quotation in Dominic Manganiello’s book is the exchange between a customer in a Roman wineshop after Joyce had left and the proprietor: ‘E socialista il Signor Giacomo?’, eliciting the dry reply: ‘E un po’di tutto.’ (‘Is Mr James a socialist?’ ‘He’s a bit of everything!’)

The most revealing anecdote about him came to me from a friend, T. J. Kiernan, then in the Irish High Commissioner’s office in London overlooking Piccadilly Circus. After a long and late dinner one night somewhere in the vicinity, the two men strolled about for a while until Joyce said he needed to urinate. Kiernan led him to the nearby High Commissioner’s office, by then a quite empty and silent building, down to the white-tiled urinals beneath the level of the Circus, where Joyce, at his side, faced the white vespasiani. ‘There is nobody in this building?’ Joyce asked. Assured that they were completely alone, Joyce raised his fists beside his face and started a prolonged, high-pitched scream. When Kiernan could stand it no longer he patted Joyce’s shoulder and said that would be enough now. Joyce stopped his wild screaming, breathed out a relieved ‘That’s better,’ buttoned, and the two went up and out into the crowded circus of the world.

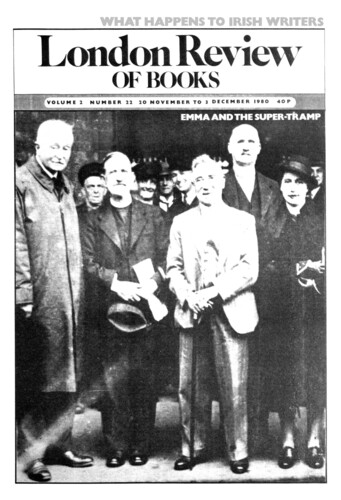

Alienated beyond recall. Self-exiled ever since the day when, as Dedalus, he saw that long-legged, bare-thighed image of innocence standing among the mirroring pools on Dolly-mount Strand, his idealised image of Nora Barnacle from Galway, an elemental, untutored, unspoiled, ignorant goose girl: her very name is a synonym of the original Gaelic form that means a wild goose, common in the West of Ireland as Coyne, Kilcoyne, Quinn, Coen and even Cohen, which had he known it could have amused the later Joyce. He had fled with her to Austria and Italy, shivering, half-starving, patching, begging, borrowing so that he might write what he wanted to write, unyielding rebels both. And now here he was, nearly fifty, returned publicly to make his wild goose a respected married woman, to legitimise his bastards, trying to persuade the English clerk at the registry office that she and he had been married before, only to be told smartly that in that case he would have to be divorced before being married again, made to feel ridiculous by the London press, it really was enough to make anyone scream at midnight in a London-Irish loo.

Poor gallant Nora. She had been through a lot with her hero. She was to lie buried beside him in their bed of foreign earth. The officiating clergyman would describe her as ‘a great sinner’. Foolish priest! She had been his heroine, saint and fate. She and Ireland had been that brown mole anchored to his breast, whatever else might be woven and unwoven within him, from the day he was born.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.