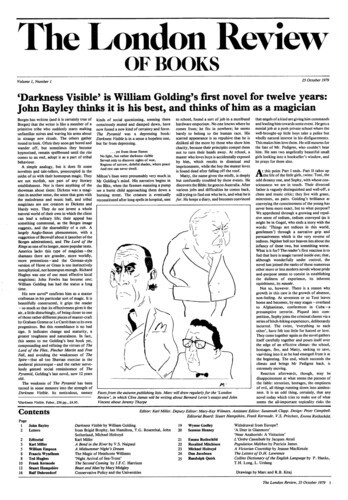

The London Review of Books is something new. This, for the first time, is it. The journal will appear fortnightly, with a summer layoff, and it will appear, for the present, marsupially or bisectingly, together with the New York Review of Books. Editorially, it will be separate and independent.

The writers we publish, and the writers and publishers whose books we review, will generally be British. There have been jokes to the effect that the same thing could be said of the New York Review, and these jokes can be taken to reflect certain realities of the English-speaking literary world. It is a world in which many books come out both in Britain and America, and, quite often, at about the same time, and in which British and American writers, and readers, are very much aware of one another. The London Review will therefore have to be very much aware of the New York Review. We may on occasion publish some of the same writers and review some of the same books, and we shan’t always be straining to make our coverage different or complementary. But it will not be hard to tell which journal is which.

The obvious difference will relate to the subjects generated by the nationality of the London Review’s readership, and by that of its contributors, some of whom worked together in the days before the New York Review was born. But we shall also be writing about American subjects, and we mean to make a point of publishing and reviewing the work of European writers from time to time. There is more in the way of international collaboration now in the intellectual life of Western Europe than there has been for a number of years. The creation of the European Community may have assisted the entente, and the Community’s troubles have not so far been such as to threaten to put a stop to it. In this as in other respects, the current issue represents the way we mean to go on, but in subsequent issues the proportion of reviewing, as opposed to other material and to advertisements, will rise. Readers will be informed of the publication in this country of books discussed in the New York Review. We shall follow the New York Review’s cover date: the two magazines will appear together in Britain and the rest of Europe, and will be on sale there in the course of the preceding month.

It is not always thought proper, or even possible, nowadays, for a literary journal to open with a statement of policy or intent. But perhaps something of the kind could be attempted by referring to the ways in which we have become accustomed to invoke, and to violate, the old idea of democracy. There is a good deal of deceit in the talk of democracy that is heard, and a good deal of hostility to parliamentary government. We shall try to treat this subject, and to pay attention to the fortunes and prospects of the social-democratic Left. And we shall do so in the belief that these concerns may have a bearing on the discussion of literature. We are not in favour of the current fashion for the ‘deconstruction’ of literary texts, for the elimination of the author from his work. Nor shall we subject his work to understandings which lay stress on a narrowly conceived public interest, or on the laws of history. This does not mean, however, that we shall go in for a worship of the author in any of the modes which have held since Romanticism, or that we would want to deny that literature should be publicly useful. The paper will be democratic in this sense, among others, while recognising that democracy isn’t everything, and that there are good writers who dislike it. Those of the writers we shall publish who object to such views can be expected to make their position clear.

Literary journalism in this country shares at present in the country’s contracted and suspended state – a state that will not improve if we keep our appointment with the worsening world recession predicted for the new year. The prestige and velocity of the ‘critical comment’, that notable and often dubious feature of the Fifties, have failed. For reasons that can’t all be separated from the facts of a national decline, criticism, and the literature it serves, have suffered a loss of confidence. But it is also true that gifted performers have arrived, and survived. New papers are starting, and old ones are resuming. There is no law of history which says that literature cannot break the spell of its dependence on the economy and on the state of the nation.

I should add that we are very grateful to the New York Review for doubling up with us and for helping us to make an early start.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.