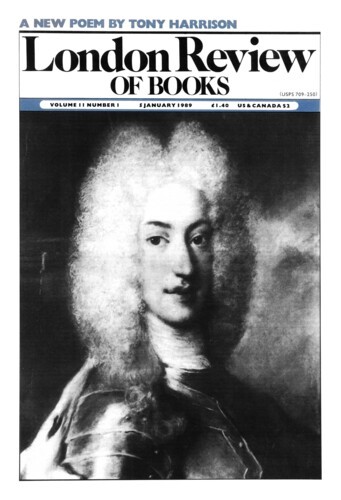

One of the most lively debates currently engaging the attention of historians, more or less the world over, concerns the so-called ‘revival of narrative’. Ought written history to concentrate on the story of great events, or is the description or analysis of structures an equally important part of the historian’s business? At a time when the pendulum seems to be swinging back to narrative, it is encouraging to find a scholar as gifted as Simon Schama moving in the opposite direction. His first book, Patriots and Liberators, published in 1977, told the story of a major episode in Dutch political history, the revolution of the late 18th century, in a fluent narrative divided into 12 chronological chapters. The new book, on the other hand, is not so much a story as a portrait. It offers, as the subtitle proclaims, ‘an interpretation of Dutch culture in the golden age’ (more or less the 17th century). The author seems to have experienced a conversion to cultural history. Not, as he is quick to point out, the history of Culture with a capital C – ‘theatre or poetry or music’. His concern is to describe and interpret what he calls the ‘social beliefs and behaviour’ of the Dutch, their ‘physical and mental bric-à-brac’, their cultural ‘furniture’. In other words, he is interested in culture in the wide, anthropological sense, or, as he sometimes puts it, in the ‘national personality’ or collective mentality’. A confessed eclectic, Schama has drawn some of his inspiration from social anthropologists (from Emile Durkheim to Mary Douglas), some from Freud, and some from the history of mentalities – the Dutch word is mentaliteitsgeschiedenis – as currently practised in France, the Netherlands and elsewhere.’

The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age by Simon Schama. One of the most lively debates currently engaging the attention of historians, more or less the world over, concerns the so-called ‘revival of narrative’. Ought written history to...