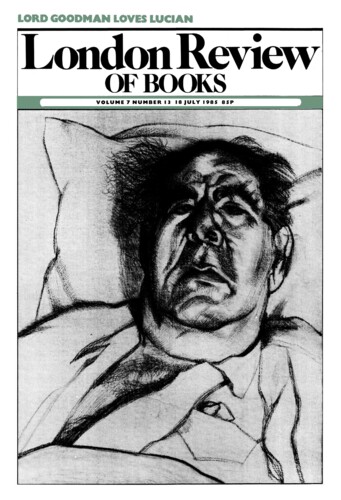

Martyrs

Lord Goodman, 8 May 1986

The enlightened editor of this publication has sent me these three books for review, having detected some symmetry which might make a joint review appropriate. All three are concerned with an aspect of freedom of speech; all three, moreover, attend to the age-old enigma of whether betrayal of a pledge can ever be justified, and if so, in what circumstances. One of them, Miss Keays’s book, can be briefly disposed of. In her case the betrayal is twofold. First, the betrayal of a lover by the desertion of her partner, and, secondly, the betrayal by the aggrieved lover of the private story of the romance. Wiser counsels – family counsels in particular – should have prevailed upon her to recognise that such a book would earn her little sympathy even among the many who had sympathised with her distress. It is indeed difficult to feel sorry for anyone who feels such poignant sorrow for herself. I am irresistibly reminded of the famous dog in Three Men in a Boat. His name, I believe, was Montmorency, and at one stage the author describes how, when someone trod on his tail, ‘he appealed to the solar system.’ This is Miss Keays’s appeal to the solar system and she will, I fear, have met the same response as poor Montmorency. It is a kindness to say no more about the book.’