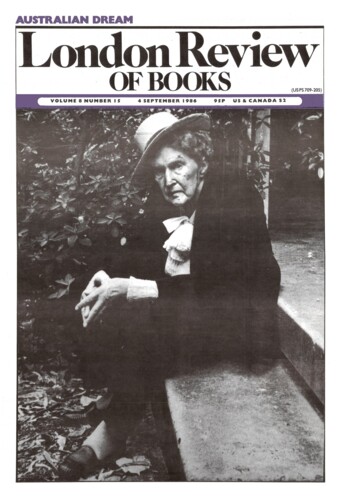

A.D. Hope reflects on the advent of an Australian literature

A.D. Hope, 4 September 1986

The publication of this work, following closely on Professor Leonie Kramer’s Oxford History of Australian Literature with its two supplementary anthologies, marks not only a new development in the standing enjoyed by Australian writing in the world but also a radical change in the point of view from which literature written in the English language must henceforth be treated. This change of attitude, which was inevitable and has been slowly imposing itself over the present century, is still not well understood and has scarcely yet been accepted. It arises from the fact that English is now a literary language in some forty countries all over the world. In some it is the main or the only literary vehicle for writers. In others such as India, Canada, Malaysia and South Africa it competes with one or more other languages. In still others, like Nigeria, it is a secondary language but provides the only outlet for educated writers since the many native tongues do not provide an adequate reading public. In all these countries the English language serves and is embedded in very different social and cultural backgrounds which are unfamiliar to speakers and writers from other areas. Major writers in all these areas are known to readers throughout the English-speaking world and now constitute the current body of English literature proper. The editors of the last couple of volumes of the famous Oxford History of English Literature were forced to recognise this fact, just as they had had to recognise, in earlier volumes devoted to the 17th and 18th centuries, that the major writers of Scotland, Ireland and Wales were an integral part of ‘English’ literature. The older view that all branches of the process outside the British Isles formed minor, and probably inferior, offshoots to the main stem must now be given up, and in view of the fact that the literature of the United States now takes at least equal status with that emanating from England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales, it is arguable that the term ‘English Literature’ ought to be replaced by ‘Literature in English’. It would at least avoid confusion in describing its field and would bypass implications of dependence or inferiority. It would help to underline the fact that the writing produced in Great Britain from this age onwards enjoys no special prestige but is simply one among many branches of a subject defined merely by the language in which it is written – as Latin literature ceased in time to have any geographical meaning.’