No Stripes Please

Inigo Thomas · Guy Burgess’s Pyjamas

‘If anyone invented homosexuality it was Guy Burgess,’ Jack Hewit once said. If Hewit is remembered for anything it is for the men he slept with, and was bullied by. Christopher Isherwood, Anthony Blunt and Guy Burgess were three of them. Burgess ‘was the most promiscuous person who ever lived’, Hewit said. ‘He slept with anything that was going and he used to say anyone will do, from 17 to 75.’ Blunt said that Burgess was very persuasive, though that sounds too reasonable: he was feral. He also knew how to put people down. ‘The trouble with you, Anthony,’ he once told Blunt, ‘is that you want to have your cake and eat it, and you want to look as if you are giving it to the poor.’

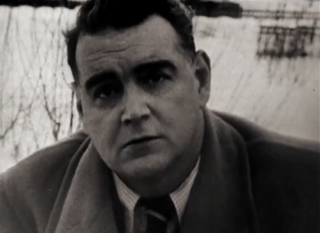

Last year, a researcher at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation found an interview with Burgess in the archives. Recorded in Moscow in January 1959, filmed outside in the cold, it is the only known television interview with him. Friends and acquaintances remembered Burgess as dishevelled – the cigarettes, the ash, the unwashed clothes, the drink. The photographic record is kinder. In the film, he wears a smart coat. His speech sounds as if it's from the pages of Ronald Firbank or Max Beerbohm, amused and epigrammatic. But it's hard to believe he’s only 47; he looks over 60, the spirits and cigarettes having got to him.

The film was shown last July at the Reform Club, and parts of it were broadcast on Newsnight more recently. The Reform was for Burgess emblematic of all the best things in life. A first-class existence and proximity to power were important to him; at the Reform Club he had all that without having to move. There was the food and drink, which weren’t rationed at gentlemen's clubs during the war. A 'double port' was Burgess's favourite – what wasn't double about the Burgess life.

He had a life-long adoration for fast cars. Harold Nicolson wrote in his diaries about having lunch with Burgess in 1943. He says nothing about their conversation, but he had the best grouse of his life. Sixteen years later, the year the interview was filmed in Moscow, Burgess wrote to Nicolson: ‘Gossip is, apart from the Reform Club & the streets of London & occasionally the English countryside, the only thing I really miss.’ Had he forgotten to mention the double port?

A man of the state Burgess obviously wasn't, but he was unfailingly a man of St James's and would be until he died. From Moscow, he carried on paying his annual membership fee to the Reform. He banked at Lloyds on St James's. His clothes came from tailors on Jermyn and Bond Streets. The actress Coral Browne, who met him in Moscow, bought clothes on his behalf and sent them on. Their correspondence was the inspiration for Alan Bennett’s play An Englishman Abroad.

‘Thanks for your kindness in shopping for me and visiting my mum,’ Burgess wrote in an undated letter. ‘I really begin to think that English women, like Russian ones, are better characters than men.’ He tells Browne he is impressed not only with her shopping but with her thoroughness: she knows how to ‘dot the 'i's in "miaow"’. Having had suits made for him and ordered Homburg hats with their rims turned up from Locke's, Burgess has a last favour to ask: pyjamas.

What I really need, the only thing more, is pyjamas. Russians ones can't be slept in – are not in fact made for that purpose. What I would like if you can find them is 4 pairs (2 of each) of white (or off white, not grey) and Navy Blue Silk or Nylon or Terrylene [sic] – but heavy, not crêpe de chine or whatever is light pyjama. Quite plain and only those two colours... Don't worry about price... Gieves of Bond Street used always to keep plain Navy blue silk. Navy and white are my only colours, and no stripes please.

Browne suggests Burgess might be interested in meeting Paul Robeson, who was also living in Moscow. But Burgess doesn't think he's up for that:

In spite of you suggestion, I found myself too shy to call on him. You may find this surprising but I always am with great men and artists such as him. Not so much shy as frightened. The agonies I remember on first meeting with people I really admire e.g. E.M. Forster, (and Picasso and Winston Churchill – but not W.S Maugham). H.G. Wells was quite different but one could get drunk with him him and listen to stories of his sex life. Fascinating. How frightened one would be of Charlie Chaplin.

In the film, Burgess talks about being a ‘non-party Bolshevik’. ‘It’s no use me saying I'm not a traitor,’ he says. ‘That means nothing.’ But in his taste for pyjamas, in his fear of Charlie Chaplin, the traitor in Burgess isn't present at all.

Still, it wouldn't be right to say life for Burgess was all about pyjamas, drink and sex. He was, and is, easy to under-estimate. Writing to Nicolson in 1962, Burgess said:

Stendhal's 'The Pistol Shot in the Theatre', the thrust of political exaction and ideology into personal circumstance, as the author writes, have always at and for me. You were born too early to be hit by this at the age at which one acts, & the intelligentsia of the 40s and 50s were both too late. I was of the generation of the pistol shot in the 30s. I notice the intellectuals of the 60s, the young at Aldermaston, have again been hit by the continuing fusillade. I notice this with pleasure one greets others getting into the same boat; and with sorrow that they don't know how rough the crossing is.