Hey ho, the wind and the rain

Robert Hanks

When that I was and a little tiny boy, or at any rate about 14 years old, I was deeply disconcerted by J.G. Ballard’s novel The Drowned World, set in a London submerged by the melting of the polar icecaps under a tropical swamp. Now I see it for the utopian dream it was – tropical? We should be so lucky. Hey ho, the wind and the rain.

Fantasies of inundation are deeply embedded. According to Irving Finkel, in his new book The Ark before Noah, around 300 flood narratives have been documented in different cultures, across every continent. Hollywood has been curiously inept at exploiting this fixation: Kevin Costner’s folie de moiteur Waterworld, at the time the most expensive film ever made, bellyflopped at the box office; Evan Almighty, the comedy update starring Steve Carell, did better commercially but was in its way just as bad; and rumour has it that Darren Aronofsky’s Noah has been going down like a torpedoed cruiser with preview audiences.

Aronofsky appears to have interpreted the Bible story as a survivalist fantasy, in which Noah (Russell Crowe), a combination of John Galt and Mad Max and spry for a 600-year-old, fights off a bunch of freeloading morlocks, led by his brother-in-law Tubal-cain, desperate to hitch a ride on his hard work. Tubal-cain stows away in the depths of the Ark, living off the flesh of hibernating lizards. And he’s played by Ray Winstone. Sometimes God hears our prayers.

The trailer shows off some impressive CGI animals, especially a carpet of reptiles slithering to safety, unaware that Winstone awaits. But Christian and Jewish groups have been antagonised by the film’s deviations from Genesis – the addition of Noah’s adoptive daughter Ila, for example, to provide a part for Emma Watson, and the fact that Noah is aided in the fight scenes by, if I’ve understood this correctly, six-armed fallen angels. To be fair to Aronofsky, at least some of his deviations – such as Tubal-cain being the brother-in-law – are derived from Jewish tradition.

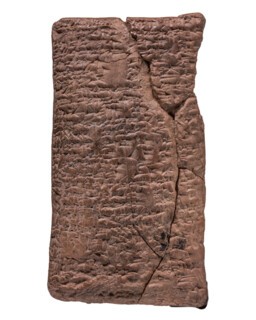

But I don’t suppose his critics will be much more receptive to that line of argument than to Irving Finkel’s message, which is that the Genesis version is just a big rip-off from the Babylonians and doesn’t even get the details right. Finkel’s big discovery is a cuneiform tablet, part of the account of the flood in the Akkadian epic of Atrahasis, containing notes on the construction of an ark – made out of rope and pitch, none of that gopher wood rubbish, and circular: in effect, a giant coracle. (An exciting footnote for people who grew up in Britain in the early 1970s: the tablet was the property of the late Douglas Simmonds, who played Doughnuts in the children’s TV comedy series Here Come the Double Deckers.)

Aronofsky’s critics have also been annoyed that the film is too liberal. As a commenter at the Christian News website put it, 'Hollywood is owned by the homosexuals. They are never going to honestly portray the true reasons for the destruction of Noah’s world, which were the same as those of Sodom & Gomorrah (see Luke 17:20-37). Don’t expect Hollywood to do God’s work for YOU because they get their paycheck from the Devil and that will never ever ever change.'

A similar view was put forward on this side of the Atlantic by David Silvester, a UKIP councillor in Henley-under-Thames, who declared that our local deluge is God’s response to the legalisation of same-sex marriage. Though it strikes me as more likely that He's taken offence at the news that the Council for Learning Outside the Classroom has awarded a 'quality badge' to the Noah’s Ark Zoo Farm in north Somerset, Britain’s only creationist zoo. And the rain it raineth every day.

Comments

Hal Clement's 1980 novel The Nitrogen Fix is about a future Earth in which not only have the icecaps melted, but all the free oxygen has disappeared from the air, making the distinction between underwater and above-water life somewhat academic. Humanity survives in the form of underground city dwellers and ocean-going traders. The plot is a bit cerebral, like most of Clement's work, but would still make a good non-action movie (nowadays we have only two movie genres, action and non-action).