By the 1780s, when the German writer Pierce von Campenhausen visited the Ottoman dependency of Moldavia, its capital, Iaşi, belonged to an Orient that would be familiar to readers of Edward Said. A ‘degraded’ populace was mesmerised by ‘the constant expectation of the arrival of some fatal order’: the gorgeous costumes of the women rendered ‘their indolent languor peculiarly voluptuous’; doubly supine, the ladies at court were ‘characterised by a melancholy cast of countenance, which derives increased interest from the unequalled beauty and animation of their eyes’. Did Jean-Etienne Liotard read Ekaterina Mavrocordato, the wife of Iaşi’s governor, in similar style when he drew her in 1742? Pathos seems to tinge his pencilwork, as if the exquisitely patterned robes had trapped Ekaterina in a gilded cage.

The itinerant portraitist from Geneva – the subject of the Royal Academy’s fascinating new exhibition, until 31 January – could offer sharp-edged yet sensitive records of appearance to his clientele in Iaşi and Constantinople, where he had worked the previous four years: it was not for nothing that a later patron compared Liotard to Holbein. But maybe the East also offered a late arriver, about to turn forty, ways to develop a personal aesthetic. What’s most striking, as you look around the eighty-odd pastels, oils, drawings and miniatures gathered in the Sackler Galleries, is the blare of intense copper-carbonate blue resounding through so many of the sitters’ costumes. Answering strains of a hot rose-vermilion are muted here and there due to the pigment’s evanescence. The colour scheme compares to the cobalt and red bole that dominate Turkish Iznik tiling. And as in Turkish art, depth is generally avoided – the wall behind most sitters seems to be the surface Liotard is working – while the emphases fall on fabric patterns.

Liotard, who had trained in Paris, liked to insist on the naturalism of his art. The claim had its place in a quarrel he was waging, partly with other contemporary pastellists, such as the Rococo master Quentin de La Tour, but ultimately with the legacy of Rembrandt. Chiaroscuro and painterly flash were wrong: they didn’t look like ‘nature’ to the untrained eye of what Liotard called the ‘ignorart’. The ‘ignorart’, whether an Easterner, a bourgeois gentilhomme or a grandee, deserved better than the condescension of art-world coteries, and Liotard, with his punctilious observation and consummate control of pencil and pastel, could supply the lucidity he yearned for.

In fact, Liotard had an advantage over the coteries. When he headed back west again in 1743, it was with a singular sales stratagem he’d sprouted in Iaşi: a vast amorphous beard of the kind a Moldavian boyar might flaunt. In clean-chinned Vienna, Paris and London, the combination of beard, pug physiognomy and Ottoman wardrobe created a comic sensation – abetted by a succession of self-portraits in this guise. Court doors opened readily to welcome the novelty act, and the clients didn’t blink at Liotard’s equally outlandish prices. ‘Self-fashioning’, the cultural historians demurely term it: ‘making a prat of yourself’, the rest of us. Most of Liotard’s art-world contemporaries fell, not surprisingly, into the latter camp. ‘The very essence of Imposture’, Joshua Reynolds remarked. And along with the charade of ‘le peintre turc’, Reynolds condemned the art itself: ‘The only merit in Liotard’s pictures is neatness, which, as a general rule, is the characteristic of a low genius, or rather no genius at all.’

Reynolds’s opinions usually carry some weight – nonetheless in this case he is demonstrably unfair. Liotard’s ‘neatnesses’ are indeed captivating. Pastel was never less sketch-like than in his portraits, with their dense, sumptuous, seamlessly modulated renderings of flesh and fabric, their delicate filigrees. The medium’s fragility has been one reason for the rarity of Liotard exhibitions, but then his works were mostly made not for public show but for individual possession. And it is the intimate Liotard, the artist as good listener, that Reynolds ignores. A clown might make a good confidant, bypassing formalities and the kind of rhetorical flattery expected elsewhere: he might perform the deeper flattery of meeting you on a level, in the flux of your feelings.

Children flourish in this regard. One star of the show is a tremulous, sickly five-year-old Hanoverian princess, staring, lips parted, at the strange man who is staring at her. Another is Liotard’s own daughter, holding fast to her doll. Marie-Antoinette as a child archduchess is preposterously pert, brimming with a self-assurance to which only the very young and very rich can lay claim. Grown women thrive likewise: from smiling French actresses to a severe elderly citoyenne of his native Geneva, Liotard’s empathy has a wide range. Those evanescent smiles, captured by the speed of his favoured medium, lift the viewer into the lightness of heart you might wish on the mid 18th century. The hang becomes that charmed space in which expectations turn, not on fatal orders, but on moues, japes and badinage – a Shandean Enlightenment. In such a dispensation, one might cast the eccentric as the norm and marginalise a sobersides like Reynolds.

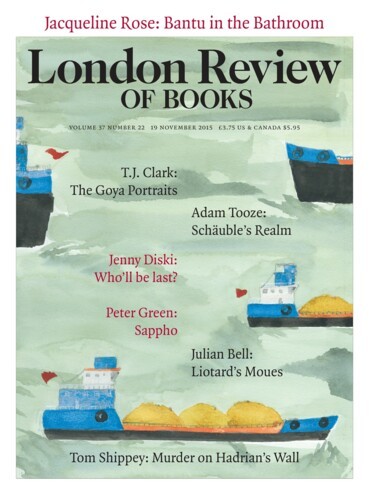

Gravity has a way of swinging back, however. The final room in the round of galleries brings together a few trompe l’oeils from Liotard’s sixties – Sternean pranks, played with the low relief at which he was so expert – with quieter, graver, old-age ventures into still life. With these fruit baskets of his ninth decade, Liotard (who died a month before the Bastille fell) bowed inevitably – but very gracefully – to Chardin, his mighty predecessor. Before leaving the gallery, however, I caught sight again of exhibit No 1. It’s a half-length self-portrait in oils, painted when Liotard was nearly seventy. The precision of the rendering is astonishing, as it is throughout the oeuvre. The artist stands before a curtain drawn onto darkness and, facing the viewer with a roguish gap-toothed grin, points a finger. What is he pointing at? ‘This way please – welcome to my world!’ is the reading encouraged by its position in the hang. But this is fine art, not signwork. It’s a canvas by a worldly-wise success who knows his Rembrandt and his La Tour (the gesture seems borrowed from the latter) and who wants, at this stage in his career, to be treated with like respect while at the same time wanting to refuse the accumulated complexity those artists subscribe to, or at least reduce it to a tease and a riddle. Ha, ha, ha. I have my doubts I really like this man.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.