When she arrived at the Slade, in 1910, Dora Carrington looked quite conventional. But she soon hacked off her long hair into an androgynous bob. Her sophisticated friends Barbara Hiles and Dorothy Brett went bobbed too and the three became known as the ‘Slade cropheads’. They wore baggy smock dresses modelled on Augustus John’s gypsy drawings and found themselves written about – in both admiring and satirical terms – in the college magazine. For all her later fame in the close orbit of the Bloomsbury set, Carrington had a modest upbringing as the daughter of a railway engineer in Bedford. Under the Slade’s fearsome drawing tutor, Henry Tonks, she worked hard enough to make sure she won a scholarship to extend her studies, chiefly – it seems – so that she wouldn’t be forced to go back home. In 1926 she wrote to a friend from her parents’ house: ‘Here I am plunged in the middle of Benares brass life, and Japanese screens … I am too depressed by the hideousness … and the bric-à-bracs.’

At the Slade, she was part of what Tonks declared the school’s ‘second, and last, crisis of brilliance’ (following the one a decade earlier brought about by Augustus and Gwen John, Wyndham Lewis, Spencer Gore etc). Her fellow students included C.R.W. Nevinson, Mark Gertler, Paul Nash and Stanley Spencer. Together they are the subject of David Boyd Haycock’s compelling group biography, A Crisis of Brilliance: Five Young British Artists and the Great War (2009), and now also of an exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery (until 22 September). Gertler became obsessed with Carrington. Nash was in love with her too. Nevinson, also smitten, fell out with Gertler over her. Stanley Spencer went to classes with them during the day, but was always keen to get back to his beloved Cookham in time for tea (for him there was almost certainly no Friday Club – a weekly soirée of painters brought together by Vanessa Bell).

Gertler’s painting of Carrington from 1912, Portrait of a Girl in a Blue Jersey, doesn’t suggest much of the charisma she must have had. Acres of blue jersey against a blue sky, with staring blue eyes, her bob painted on like a helmet: it all looks rather severe. But perhaps that was the charm. In a letter of 19 June 1912 Gertler wrote that he had ‘come to the conclusion that I love you far too much for us to be merely friends … I am afraid we must part for always,’ and listed five ‘advantages’ she would gain by marrying him:

1. I am a very promising artist – one who is likely to make a lot of money.

2. I am an intelligent companion.

3. You would not have to rely upon your people.

4. I could help you in your art career.

5. You would have absolute freedom and a nice studio of your own.

He added: ‘I know of course that you would not agree to this.’ He was right, but so was Virginia Woolf. ‘A sturdy figure,’ she wrote in 1918, ‘& a fat decided clever face.’

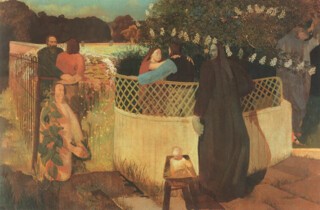

The Dulwich exhibition, curated by Boyd Haycock, is varied and incoherent, a little like a posthumous degree show. It’s almost awkwardly clear from the first room that Spencer is going to emerge as the star student. In a series of self-portraits done on Professor Tonks’s orders, Spencer’s – in red chalk on paper, with rugged cross-hatchings and a steady gaze – is the one that stands out. His Nativity (1912) hangs in the same room, painted when he was 21 for the Slade’s summer composition competition (it won). Mary, Joseph and the others stand about in a suburban garden complete with garden fence and trellis, paving slabs and iron railings. It ‘celebrates my marriage to the Cookham wildflowers’, he later said. He often felt that way. Of Apple Gatherers (1912-13), his ‘first ambitious work’, he said: ‘I felt I could kiss the canvas all over just as I began to paint.’ Nobody would want to kiss Gertler’s The Fruit Sorters (1914), which hangs heavily next to it, though Sickert kindly praised its ‘well-supported and consistent illumination’.

The students had the luck to be at the Slade in the year Roger Fry’s exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists scandalised the Pall Mall Gazette (works by Matisse, Manet, van Gogh, Picasso and Gauguin being ‘the output of a lunatic asylum’). Carrington went back to Bedford completely transformed. Her brother reported that her new opinions on art ‘deflated all our previous conceptions; those revered elders, Lord Leighton, Alma-Tadema, Herkomer and company were brushed aside as fit only for the dustbin. Who were we to look to, then? Why, Sickert, Steer, John, McEvoy: names unknown to Bedford, and even these were not to be mentioned in the same breath as Cézanne.’ Carrington’s art-loving mother found it all ‘rather humiliating’. At the Slade, Tonks summoned his students and told them ‘how very much better pleased he would be if they did not risk contamination but stayed away’. He told his colleagues: ‘I shall resign if this talk about Cubism does not cease; it is killing me.’ In 1913 he had David Bomberg expelled for associating with Marinetti and the Futurists. Bomberg went straight to Paris to spend time with Picasso and Modigliani, and despite being courted by Wyndham Lewis as a Vorticist fellow sympathiser, he chose to go his own way. He was virtually ignored in his lifetime and long beyond: it was only after a show at the Tate in 1988 that he came to be seen as the best of the bunch, if you leave aside the kooky painter from Cookham. Bomberg is missing from the main cast of Boyd Haycock’s book, but not from the exhibition: his In the Hold (1913-14), made soon after he was thrown out of the Slade, is a kaleidoscopic, jaggedly geometric, brilliant riot of colour.

The other thing that happened to these artists was the war. It was the making of Nevinson, whose dabblings with Futurism – viaducts, boats, ports – now had a subject to suit them. La Patrie (1916), made after his work with the Friends Ambulance Unit, shows the injured and dead laid out on the floor of a French railway shed. A grim silver light shines on the distorted, screwed-up faces of the injured and illuminates their bandages and dressings. A covered-up body is being shuffled in through the door; presumably it will take its place at the back of the shed, which is almost totally dark, and where bits of bodies can be glimpsed in the gloom. The train carriage outside suggests there are other bodies waiting to be brought in. Since the men laid out in the third row weren’t really men anymore, the picture’s public no longer found it strange that they were painted as abstract shapes with broken angles.

Carrington’s portrait of her companion Lytton Strachey, also made in 1916, which hangs on the wall perpendicular to La Patrie, is a shocking, almost offensive contrast to it. The men in Nevinson’s painting are lying on the ground either dead or in agony. Strachey, the conscientious objector, is lying against a pillow, holding up a book with his long, delicate fingers. Carrington began painting it shortly after one of her brothers went missing during the Somme offensive. She wrote to Strachey after finishing it: ‘I would love to explore your mind behind your finely skinned forehead. You seem so wise and very coldly old. Yet in spite of this what a peace to be with you, and how happy I was today.’ In 1917 they bought a large house together by a river in Berkshire. She told him: ‘I say twenty times a day how lucky I am to live in such a lovely place!!!’ There’s a painting of the view in the show: water, trees, vast expanse of lawn. ‘The true life of an artist,’ she wrote, ‘is I am sure all connected very closely with birds singing, & branches against the sky.’ She did like life in the country.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.