The exhibition Moctezuma: Aztec Ruler, at the British Museum until 24 January 2010, is sombre and disturbing – the chirpy half-rhyme in the title hits a wrong note. (The catalogue says not only that Montezuma is better spelled Moctezuma, but that his subjects are properly called Mexica, not Aztec.) What is shown is fascinating but often repellent. The carvings of skulls, hearts, feathered serpents and individual figures have a lugubrious weight, the bird-beaked gold ornaments are fierce, the figures ground out of hard greenstone, indeed all the free-standing figures, have a totem-like frontal symmetry. Many menace the viewer with staring eyes. The richest and most colourful objects, like the turquoise mask on the poster, are finely crafted, but the snarl of large white teeth threatens. In its own time much of what is here was frightening because it was supposed to be. The message is that the future is uncertain, that bad times are probably coming, that nature is malicious and must be propitiated.

The catalogue is not easy to read: a picture of the early history and late collapse of Mexica society must be extracted from overlapping contributions that draw on different disciplines, and one’s inexperienced tongue stutters over the names of the Mexica Gods: Coyolxauhqui, the moon goddess, her brother Huitzilopochtli, who defeated and dismembered her, the sun god Xiuhtecuhtli. But it is worth the effort; particularly as the story of Moctezuma’s empire and the nature of its downfall treats anxieties and problems oddly close to our own.

Scenes of hell in pictures by Signorelli or Michelangelo, like the ghouls in a horror movie, are now less a real fear than a safe thrill. Contrast those with a reading of Moctezuma’s coronation stone. It is a rectangular slab of basalt, carved in low relief on all six sides. In the exhibition it stands on its side; originally it was probably laid flat on the ground, so the rabbit with improbably large Bugs Bunny teeth would have been hidden. This date glyph (1 Rabbit) relates to the creation of the earth: it is the ‘calendar name’ of the earth goddess Tlaltecuhtli. In each corner of the upper face a glyph represents a past era; three ended in entirely familiar modern disasters – hurricane, flood and rain of fire (volcanoes?). The fourth, a plague of jaguars, is more exotic, but the glyph in the centre of the rectangle that represented the current era, the one during which Moctezuma would have to keep the forces of nature at bay, predicted earthquakes. The disasters the Mexica knew or dreaded are those we see on the news, or have explained to us over sonorous music in science documentaries. (We turn the plague of jaguars on its head and fear their disappearance rather than their proliferation.) Round the stone, filling its narrow sides, are four images of Tlaltecuhtli, her skirt decorated with skull and crossbones: ‘Her open mouth and bared teeth remind us of the constant sacrifices needed to feed the earth and to maintain the stability of the present era,’ the catalogue reports.

Then as now, society was vulnerable both to the forces of nature and to inherent instability. Moctezuma’s city, Tenochtitlan, occupied an island in the shallow lake that once spread across the basin of Mexico on the site of what is now Mexico City. When Cortés arrived in November 1519 the island population may have numbered as many as 200,000. The city was rich, supplied with staples from surrounding territories and luxuries from more distant provinces: bird skins and feathers, cacao, cochineal, live eagles, salt, seashells, jaguar and deer skins, canes, chillies, cotton, turquoise, paper, gold and greenstones. Tribute was enforced by wars fought by a warrior aristocracy that was rewarded lavishly with gifts and whose captives supplied the hearts and blood the gods hungered for. Not all battles were won, but the warriors expected their presents even so, and an expanding population needed feeding. The tributary provinces and alliances of the Mexica empire that supplied the city’s needs were, like famine, a threat, and famine was not a theoretical disaster. A prolonged drought began in 1451; by 1454 there was nothing to eat and traders travelled from the coast to purchase the Mexica as slaves for a few corncobs. Horses, steel weapons and smallpox enabled the Spanish conquest, but it was aided by disaffected subjects.

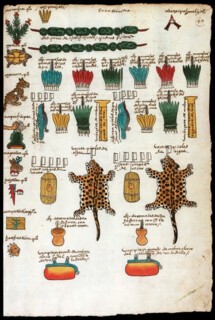

Three kinds of material are on show in the exhibition. There are objects connected with Moctezuma and his kingdom: carvings, weapons, gold work, jewellery and so forth. There are paintings and engravings, made after Moctezuma’s defeat and death, that record the events of the Spanish conquest. And there are manuscript ‘codexes’ made by Spanish ecclesiastics or by descendants of the Mexica ruling class in the latter part of the 16th century. In the codexes what was known and remembered of the history, customs and culture of the Mexica people is recorded. Several codexes are on display; it is from accounts in the catalogue based on them that one gets some notion of the lives of the Mexica. Artist-scribes working in the indigenous tradition produced sheets in which pictographs and diagrammatic representations are combined with alphabetic transcriptions. Two pages from the Codex Mendoza identify things to be delivered to the Mexica royal court in a style very like that used by a modern pictorial encyclopedia when it lines up diagrammatic ears of corn, say, to compare agricultural outputs.

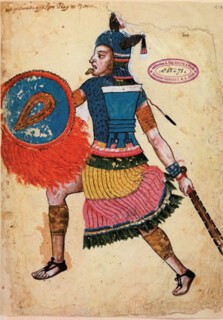

A fragment of a giant sculpture of a rattlesnake, the scales and rattle wonderfully well observed and confidently carved (the kind of thing 20th-century sculptors looked to and admired when they were pursuing authenticity by doing direct carving), was once part of a decoration in Moctezuma’s palace. It is evidence of its size and splendour. There is much information available about what the Mexica ate and how they dressed. Now that body piercing is commonplace it is easier to imagine the effect a gold eagle-headed labret might have had when it was plugged into the lower lip of a warrior (one of the nastier humiliations suffered by captured warriors was to be left constantly dribbling after the removal of their labrets). Modern fashion has also made the large ear-spools easier to envisage in use than they once would have been.

The feelings that sustained the ritual life of Moctezuma and his people are harder to imagine. We know its outward manifestations in considerable detail. The gods were thirsty for blood; the ruler supplied it in small quantities at his investiture from scratches made with the sharpened bones of eagles and jaguars; human sacrifices supplied it in quantity. The Templo Mayor, still being excavated in the centre of Mexico City, was topped by the twin temples of Tlaloc, the rain god, and Huitzilopochtli, the Mexica ancestral hero; a representation by a Mexica scribe in a late 16th-century manuscript shows blood flowing down steep steps from the temple doors. It gives one a chill, as might the wiring diagram for an electric chair.

The abundance of material that can be traced back to native sources shows up the aesthetically undistinguished images in the Western tradition included in the exhibition: the long early 18th-century screen describing scenes from the conquest of Mexico in overwhelming and confusing detail, for example, or the late 17th-century portrait of Moctezuma, commissioned by Cosimo III de’ Medici. We now have more real objects and more near-first-hand accounts to draw on. But when it comes to sacrificial blood, the Spaniards, who in the 17th century developed a style in painted sculpture that put much emphasis on Christ’s wounds (it is the subject of a current exhibition in the National Gallery), had much in common with the Mexica. For them, too, anxiety about divine intentions and the need to ask for divine intercession were facts of life.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.