An exhibition of Osbert Lancaster’s drawings, cartoons, illustrations and set and costume designs, selected by James Knox, will begin at the Wallace Collection on 2 October. Lancaster was a short man with a big head, strikingly large blue eyes, a curled moustache and a dandy’s taste for very good, but emphatic clothes (pink shirts, bow ties). He surveyed English society from a secure promontory. An upper-middle-class upbringing, public school and Oxford delimited the foreground. Friendship and work extended the view but did not change it. It was an ideal position – secure, informed, confident – from which to make jokes about England, its classes, styles and politics, and the effect on them of encroaching modernity. In his autobiography, All Done from Memory, he draws himself wheeled in his pram by Nanny in Kensington Gardens and cooed over by a veiled lady with an ermine muff and hat, and in another illustration he is taking tea with aunts whom Lartigue would have been keen to snap.

In his guides to British architecture (Pillar to Post and Homes Sweet Homes), the excesses of the latest thing are identified. The story advances spread by illustrated spread, so that ‘Early English’ and ‘Modernistic’ get the same degree of attention – architectural history is cut down to size. Baroque excess (‘A taste for the grandiose, like a taste for morphia, is, once acquired, difficult to keep within limits’) is characterised as uncompromisingly as ‘Stockbrokers’ Tudor’: ‘All over the country the latest and most scientific methods of mass production are being utilised to turn out a stream of old oak beams, leaded window panes and small discs of bottled glass.’ The details in the black and white line drawings are wonderfully precise: not just of mouldings, doors and table ornaments, but of inhabitants too. That the furniture in ‘20th-Century Functional’ (bent plywood, Aalto perhaps) and the Bauhaus light fitting should be correct is good homework: getting the slippers, spectacles and soft-collared shirt of the owner right shows the craft of a theatrical designer – Lancaster distinguished himself in that career too. The best of these drawings epitomise the period in jokes that don’t at all interfere with accuracy. Some of Lancaster’s labels (‘Pont Street Dutch’, ‘Stockbrokers’ Tudor’) have entered the language. Standard ones like ‘High Rise’, in the illustration for which a Ronan Point-like explosion blows concrete, pram and mother from the ninth floor of ‘Benn House’, include details that tell things photographs taken for architectural journals will not: the way net curtains were looped and bicycles parked on the balconies.

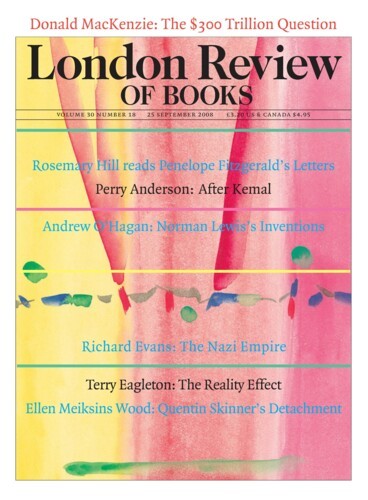

In the book accompanying the exhibition, Knox describes the daily routine Lancaster settled to.* It combined a Bertie-Wooster-like rhythm (morning, sit in dressing-gown, dress at noon, lunch at the club, some sort of conviviality in the evening) with un-Woosterish hard graft, according to his daughter: ‘Imbued with the Victorian work ethic of the Lancasters, which, true to the family code, remained uncorrupted by his private wealth, Osbert never let up … he was always in the studio – working, working.’ So the dressing-gowned morning was spent writing or drawing, and after lunch there was the trip to the Daily Express where, for almost forty years, he produced the daily pocket cartoons, pictured here, that now stand as a history of forgotten headlines and passing fashions – he had a particularly good time when girls wore tight sweaters, short skirts and fishnet tights. Of Maudie, Countess of Littlehampton, who became the most regular inhabitant of the pocket cartoons, he said: ‘Having started as a slightly dotty class symbol she’s been increasingly useful as a voice of straightforward comment, which might be my own.’ Her remarks come in scenes that give glimpses of her social life: cross-examining a permanent secretary at what must be a grand party – his KCMG shows below his white tie and she is wearing long gloves – or drinking champagne on top of a charabanc at Epsom.

The voice has much in common with those of the most memorable English comic novelists of the mid-20th century; they all gathered on the same upper-middle-class promontory. We didn’t much mind, even when Noblesse Oblige, Nancy Mitford’s ‘inquiry into the identifiable characteristics of the English aristocracy’ (it included Lancaster’s illustrations, Betjeman’s poem ‘How to Get on in Society’ and a contribution from Evelyn Waugh) brought home the fact that the identification with the narrator, always a one-way traffic, was in this case disguising the social distance travelled. Lancaster’s contribution to our knowledge of what grander scenes than those we have experience of looked like was considerable. He did drawings for the paperback covers of Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time and Venusberg, the latter showing a party attended by diplomats and officers sporting medals and sashes of the kind that had engrossed the young Lancaster when he found them in the photographic supplements of turn-of-the-century Picture magazine. In clothes, as in buildings, his accuracy is remarkable. He left a record of changes in how people look and act to match that of the contemporary Punch cartoons he admired.

In the architectural satires, encroachment of the new is displayed graphically. In Drayneflete Revealed the same crossroads, ‘Poets’ Corner’, moves, generation by generation, towards traffic-clogged incoherence. Each incursion – the Odeus cinema, the modernised pub – squeezes the increasingly dilapidated Gothick villa that gave the crossroads its name in 1800. Our world, these drawings say, is going to the dogs.

But there were things to do about that. One of Lancaster’s contributions was a series of drawings for the 1974 V&A exhibition The Destruction of the Country House. They showed what would, by then, have become of famous houses in fiction. Mansfield Park is now a girls’ school with a new wing by Basil Spence and what looks very like a CLASP classroom block. CLASP buildings (the acronym stands for Consortium of Local Authorities Special Programme – a prefabrication system used between 1957 and 1980) have lately been shown to have problems with leakage of asbestos. Lancaster might not have been surprised. The soullessness of modernity in architecture and the ruthlessness of all kinds of development – private as well as public – were beasts too big to do more than quiver a haunch at Lancaster’s jabs. Nor was the situation a new one: Ruskin was unhappy about railways, and the spread of industrial cities could make no aesthete happy. But Lancaster, and friends like John Betjeman and John Piper, were part of the movement that encouraged action. Neither Preservation Societies nor the refinement of planning zones could do much about making a new world to their taste, but they did safeguard things that would otherwise have been smothered.

The pocket cartoon is not dead – Matt in the Telegraph is often very funny – but the place from which Lancaster viewed the world has lost its identity. The anarchic invention of Steve Bell’s strips in the Guardian matches our time; Maudie’s sharp exchanges with men in suits are mementos of a differently ordered set of absurdities.

A technical note. In the book most of the cartoons (even the black and white ones) and most of the jacket designs are reproduced from the original artwork. This has a certain nostalgic charm for those of us who can remember whiting out unwanted lines and shading areas in blue pencil to show the block-maker where to lay a halftone tint. Reproductions of graphic work from this period that are true to the artefact – the drawing – can get in the way of truth to the artist’s intention. One can see why the decision was made, but it takes the cartoons a step away from the world of Fleet Street and letterpress printing, of which they were a notable ornament.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.