To the National Gallery in search of hands and feet. It is Sunday and by coincidence a procession crosses my path holding stools and drawing books. From what I can see on the odd sheet this seems to be the ‘drawing hands’ workshop signposted at the Education Entrance.

The hand is a testing subject, although not as difficult as the ear, according to Agostino Carracci, who with his brother and cousin founded the academy in Bologna that set the model for much subsequent art education. The foot sets problems all of its own.

The bit of the brain that specialises in recognition is as willing to pay attention to a face that is relaxed, glum and still as to one that is pulled about expressively. With the extremities, however, it is gestures we attend to: a flexed wrist, a pointed toe, spread fingers. Faces are recognised for themselves, hands and feet for what they say. I’m not sure that I would recognise my own feet in a photograph, or anyone else’s, although hands and feet differ as much as faces: plump when young, wrinkled when old; delicate or clumsy; long and thin or short and thick. The individuality that resides in the sum of such differences is not easily recalled.

Moving from portrait to portrait in the gallery you see that the concept of likeness doesn’t seem to extend to hands. They tend to be generic, specific to an artist, even in portraits. Did all Van Dyck’s male sitters really have the long-fingered, blue-veined hands that Lord John Stuart and his brother Lord Bernard share with the Abbé Scaglia and so many others? Were the hands of Rembrandt’s sitters really all solid and paw-like? Those of Jacob Trip, his wife, Margaretha de Geer, and Hendrickje Stoffels seem to be generated by the same schema, even if the first two are old and wrinkled and the last young and smooth. Madame Moitessier’s fat, flexible little octopus of a hand is at one with the personality Ingres has given the sitter; yet it is a close relation of the hands that emerge from M. Bertin’s cuffs to grasp his knees and establish, through that gesture, and despite the resemblance, an entirely different presence.

In portraits hands are nearly always still, resting even when holding a pen or a sword. Dramatic gestures look unnatural; when a lifted arm, an open palm or a pointing finger appears, a portrait takes on the character of a subject picture. Frans Hals’s Family Group in a Landscape is unusually lively because the youngest children are being offered flowers and oranges, but it is still a portrait group. His Vanitas, in which a boy holds a skull and makes a gesture towards you that foreshortens his hand, is a piece of play acting. Despite the liveliness and individuality of the face, it is not a portrait.

The Hals boy’s hand is even more extreme in its foreshortening than that of Christ, when he makes the same gesture in Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus. The hands of the disciple on the right, who stretches his arms, come out at you and go away from you. Released from the decorum of the portrait, hands take their place as expressive elements, in this case both enclosing the painted group and drawing you into its compass.

Walk round the gallery and you note a vocabulary of gesture: the downward-pointing, open-palmed hand of Christ in Mattia Preti’s mid-17th-century Marriage at Cana, like the upward pointing hand of Christ in Titian’s Tribute Money, painted around a hundred years earlier, is demonstrative, a teacher’s gesture. In neither case are the muscles of the hand tense. The open palm with all fingers spread and under stress, most memorable as a sign of masculine affirmation in David’s Oath of the Horatii, has a long alternative history in the poses of grieving women. Here you find it in Annibale Carracci’s Three Maries, elsewhere and more famously in the woman with upraised arms in Caravaggio’s Entombment. There are class differences. Peasants clasp baskets and the legs of a trussed fowl firmly, saints reach up or out elegantly. You can imagine that they were taught to hold a skirt or cloak with the index finger separated from the other three – like young ladies being taught to curtsy. That way of managing drapery turns up in portraits, too.

Sometimes painters observe truths that fall outside these essentially rhetorical traditions. Murillo’s softness and sweetness can seem cloying, but in Two Trinities Christ’s grip on his mother’s finger and the way he rests his hand in Joseph’s palm are observations of the way big and little hands take hold of each other rather than inventions. In Watteau’s pictures of guitar players, the fingers that stop the strings and the thumb that plucks them are spread and active. The drawings in which he made a note of such things are famous. Chardin’s woman teaching a child to read holds her pointer so simply that it is a moment before you realise that the same kind of observation of modest things made it possible for him to give striking presence to a plum or a pot. In Rubens’s Samson and Delilah, the barber snips at Samson’s hair with the scissor hand unexpectedly turned palm up, while his left hand reaches delicately over it to catch the cut tress between thumb and forefinger. I doubt if it was done without recourse to a model.

It is not easy to avoid hands when you paint people. In Goya’s portrait, Don Andrés del Peral thrusts his, Napoleon-like, into his waistcoat. Many of Velázquez’s sitters wear gloves (Mickey Mouse does too, and only has three fingers, both ways of making it easier to draw his hands). Fingers can be simplified into smooth shoots without nails and handless poses can be invented. But because hands have the potential to suggest feelings that would seem excessive if transferred to the face, painters have had to master their anatomy.

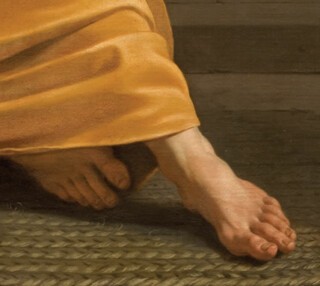

Feet are a different matter. Shoes, boots, long gowns and long grass hide them. And when they do appear they don’t have much to say. In Annibale Carracci’s Christ Appearing to Saint Peter, Jesus steps towards you, weight on his front foot, very much as the Apollo Belvedere does. There is too much of the gentleman who has been taught to walk by a dancing master about him. But although bipedalism, which freed the upper limbs to make signs, limited the potential of the lower ones, once in heaven they can kick and twist. Tiepolo has them lolling on clouds and floating upwards. Rubens so peoples his skies with cherubs that examples of baby feet can be found at any angle, while allegorical figures (often naked women) are also unshod. But they feel like variations on drawing-book examples or studies of sculpture. They fulfil their function as the termination of legs but do not have the emotional potential of the clasped hands of the Sabine women or the clawing fingers of the woman in the centre of the Massacre of the Innocents.

In Raphael’s Transfiguration Christ’s naked feet seem as significant as his spread arms, but I know only one painter who is totally at ease with their geometry – Philippe de Champaigne. In his Dream of Saint Joseph the saint’s foot is as assured and confident as the tools that lie beside him. It is the most satisfying part of a remarkable picture.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.