Objects from Africa displayed in galleries leave us bemused. We hesitate to use the word ‘art’ – this is not Giorgione or the Barbizon School or Howard Hodgkin – and hedge our bets with polite words like ‘artefact’ or ‘decoration’. African narrative and music have done better. World-music impresarios can market the virtuoso kora players of the western Sahel; we have the kitsch academic term ‘orature’ to soothe our anxieties about the fact that the greatest story-telling and poetry from this vast continent had nothing to do with pen and paper. But ritual masks, pots and cloth, or forged metal that crackles with military prowess – how are we to decipher and project these as the aesthetic truth of a continent?

The first step is to dismantle ‘Africa’ and think of it instead as various places at various times. This is what the British Museum has done in bringing back its African collections from the Museum of Mankind and setting some of the best work on display in the new Sainsbury Galleries. It’s been thirty years or more, and a note of triumph is sounded in the BM’s press release about the return of all this stuff ‘to Bloomsbury’. ‘Illuminating world cultures’ – in the new BM brand-speak – is a sophisticated affair, and what better place than Bloomsbury to illuminate a 400-year-old pectoral mask in brass from Yoruba country or a couple of wooden fish on a hat made from a cardboard mineral water case?

A little nostalgia is in order, then, for the dusty, understated entrepot of Burlington Gardens, where the collections looked more at home, entangled – it seemed – in the creeper-like attentions of the few: frayed and hollow-eyed adventurers in baggy trousers; scholars and devotees from soas; seething parties of schoolchildren from Lewisham. But there’s no doubt that the new location, in which hundreds of objects are lavishly displayed for larger numbers of people, is the better option. The difficulty is that when you take an ethnographic collection and ask people to think of it in terms of art – as these rooms do – you replace an oddball discipline, which can handle all kinds of material, with a grand categorical assertion that cannot.

Just as the African Galleries have done away with the suggestion of a single Africa, so, too, they’ve underplayed the idea of ‘art’ in favour of a sanguine anything-goes – easier for the BM, with its wealth of imperial bric-à-brac, than it was for the Royal Academy when it staged its superb Africa exhibition in 1995. In the book that marks the opening of the galleries, John Mack warns against ‘a monolithic reinvention of African culture and history’, preferring ‘to open up a new gateway into a collection that can be mined in very many ways to show something of African varieties of life and thought’. (Whence, perhaps, the decision to dust down and re-enlist that time-honoured medium, the ‘ethnographic film’ – the video material in this case less like Jean Rouch and far more like an 8mm geography-lesson module from the 1960s.)

Yet the suspicion that everything on display may one way or another be thought of as ‘art’ is carefully – and brilliantly – allowed to linger in the visitor’s mind. Mack and his colleagues had already managed this in the Museum of Mankind with their later acquisitions (only intermittently displayed). These have since been added to and are now so conspicuously placed in or about the entrance of the new galleries that there’s no getting around them. First, upstairs, a group of decorative coffins from Ghana in painted wood, the best a white Mercedes (number plate: RIP 2000), the lid removable, from headlights to tailgate, to admit the deceased. Next a kind of ideal receptacle – a curving ceramic vessel with a sphincter-like protrusion in the broad, inquiring neck. Then a pair of contemporary masquerade figures in steel, fabric, feathers, wood etc, one with a sturdy fishing-boat on its head and an apron splashed with paint – the red of sacrifice.

The importance of all these exhibits is that they are named. The coffins come from workshops in Ghana (Paa Willie’s and Paa Joe’s); the ceramic piece is by the Kenyan sculptor, Magdalene Odundo; the masquerade figures are by the Nigerian artist, Sokari Douglas Camp. It is a proper, and properly political, strategy to preface the big rooms we’re about to enter with a clutch of works whose attribution to individuals or workshops is certain. It alerts us to the likelihood that styles of popular art and more elaborate forms of homage (to notables and ancestors) were never entirely a matter of transcendent aesthetic consensus. Better, surely, to imagine competition between rival schools and individuals; disagreements, closely guarded secrets, and something resembling celebrity, which would have fallen to sculptors or carvers who set their own distinctive mark on an existing style or founded another. This, after all, is how it is in many parts of the continent now.

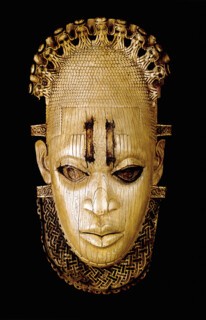

Anthropology is happy with named informants; ethnographic collection, on the other hand, seldom saw the point in attaching a name to a work, even when it was possible. Which is one reason for the longstanding belief that African art was an almost mystical expression of the collective. The Africa Galleries make this seem like a silly idea. And so one can go deep into the past, especially in the rooms to the right of the entrance, where the earliest objects are more than a thousand years old, without losing that sense of a maker who would also have had a name. Hardly strange, though, that we cannot identify the masters of the Benin metals, bronze and brass, plundered for Queen and Country in 1897. Or that we don’t know who carved the ivory pendant mask of Idia, a Benin royal mother, 400 years ago. She is not, by the nature of things, a Virgin Queen. But the hint of Tudor impassivity reminds us that the period is roughly the same – and that more than one portrait of the English monarch who underwrote John Hawkins’s second slaving-voyage along the coasts of Africa in 1564 is by an unknown artist too.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.