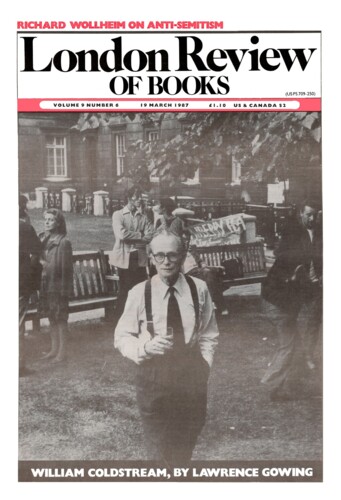

Thinking far away about my friend and teacher, who died a fortnight ago, I am aware of how many owed to William Coldstream, not necessarily, as I did, the circumstances of their whole lives, but the terms of reference through which they came to the painting and thought of their time. It must have been in 1936 that I met him at the suggestion of W.H. Auden, the friend of a friend, in the pub in Charing Cross Road nearest to Soho Square. I have told the story often – Auden had written: ‘You want to get into film because you think it is the art of the future. It isn’t. Art is the art of the future’. Coldstream looked over his shoulder back towards the offices in Soho Square. ‘My life puts whole districts of London out of bounds’. Something neither furtive nor taciturn, but functionally economical with words, put an 18-year-old, on adult ground for the first time, at his ease. He asked me what I was painting and forbade wallpaper in the background of a picture of my sister. ‘One can’t paint wallpaper any longer’. He must have thought I had a Vuillard-type pattern in mind.

Anything that savoured of art or taste was excluded. In the studio which Coldstream shared with Graham Bell in Robert Street off the Hampstead Road ‘art’ had become a dirty word, though the depth of bitterness was reserved for the word ‘artistic’. Coldstream’s time at the GPO Film Unit was coming to an end, but his association with John Grierson had a lasting effect.

I cannot remember if I became aware of the doctrine at the pub or at the Group Theatre Film School where I first heard Coldstream teach with typically paradoxical practicality. Grierson held it to be naive as well as wicked to suppose that the quality of art could be produced on purpose. It could only emerge as an involuntary by-product of an image assignment capably and selflessly accomplished. An image that must have enough social utility to make some responsible person prepared to pay for it.

For Coldstream, no question of ‘art’ arose until someone was interested enough in the image to support its production. This seemed to indicate portraiture, like the portraits of Auden now at the University of Texas at Austin, and of his mother and Mrs Berger in the Tate – all of them painted at this time and in the light of this conviction. Or subjects of equally indisputable human interest, like the miraculously integrated cat on his wife’s lap, now in the Ashmolean.

Coldstream always knew when he (or anyone else) was interested. The word was at the heart of his vocabulary and the centre of his life. He had an equal talent for knowing when he was bored. The appearance of a man or woman to be painted always engaged his attention utterly, and he was deeply interested in the quality of anyone else’s engagement. This was the commitment that gave his attitude its peculiar positiveness, its sympathy and common sense.

I have heard a qualified observer remark that Coldstream was the only natural logical positivist that he had ever met. I asked Coldstream much later (later than anyone else would have done) if we could be sure that the length and breadth of the visible aspect of a thing – the apparent height as against the apparent width of Lord Avon’s moustache, for example – composed its real nature. His answer was to demand, with signs of incipient boredom, what else it could possibly be.

Going to meet Coldstream when he was painting St Pancras in 1938, I wondered in the face of that vast elevation of terracotta Gothic how we should ever find him. In another moment the appearance through one of the windows of a rigid horizontal arm gripping an exactly vertical brush-handle up which a square-cut thumbnail was creeping in minute adjustment of the length to the angle subtended, answered me delightfully.

It was the systematic notation of measurements that stuck out conspicuously in the style of middle-period Coldstream. Or seemed to – whether anything in his subtle and complex art was entirely what it seemed must await the judgment of posterity. Real art always eludes the chronicler, but committee members recall the relief of a meeting under Coldstream’s brisk chairmanship. When the Tate acquired pictures that gave no sign of the uncomfortable tendencies for which their authors were noted, his reaction was ribald. When it accepted a Kupka of a picturesque waterfall, he was heard to remark: ‘Before he changed his name to Winston Churchill!’ Coldstream sometimes said that he thought of measurements, and of the comparative ratios on which their use depended, as the musical part of painting. The delight in them increasingly communicated itself.

But hearing a discussion like this, he would allow his attention to wander. He did not think it sensible or interesting to debate such issues. I have known him to confide that it did not matter what people painted so long as they thought it did. The data of mensuration interested him precisely because he could get his hands on it. It had a salutary impersonality; there was nothing emotional about it.

He used to explain that he hated the internal stuff of emotional expressiveness; if he relaxed his vigilance, it would come flooding out contaminating him. I have seen three or four black-toned juvenilia which were perhaps the kind of self-betrayal that inspired his reserve. I understand the decision to suppress them, because it would be a pity if anything were to weaken the lifelong testimony to lucid outwardness and to the otherness of the actual, the beauty in which he placed his faith. We have lost an enchanting companion, and a resplendent intelligence whose trust in freestanding objectivity is hardly comparable with anything else in English painting.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.