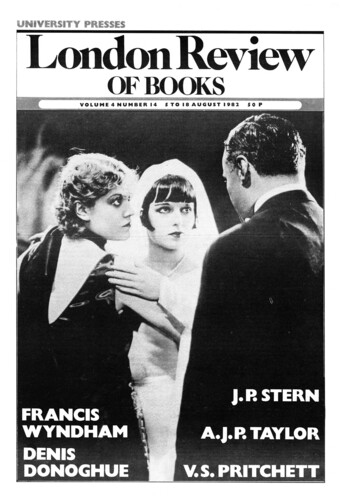

The photographs of Louise Brooks in Lulu in Hollywood show a face as beautiful, and almost as unchanging, as a Japanese mask. Both praise and criticism notice this inexpressiveness: ‘Louise Brooks exists with an overwhelming insistence ... always enigmatically impassive,’ ‘Louise Brooks cannot act ... she does not suffer ... she does nothing.’ Her writing, on the other hand, is painfully self-revealing. Sometimes funny, sometimes angry, she is unfailingly perceptive about the arts of acting and film-making. The description of Pabst’s direction of Pandora’s Box is one of the best things in the book:

Alice Roberts came on the set looking chic in her Paris evening dress and aristocratically self-possessed. Then Mr Pabst began describing the action of the scene in which she was to dance the Tango with me. Suddenly she understood she was to touch, to embrace, to make love to another woman. Her blue eyes bulged and her hands trembled. Anticipating the moment of explosion, Mr Pabst, who proscribed unscripted emotional outbursts, caught her arm and sped her away out of sight behind the set. A half-hour later, when they returned, he was hissing soothingly to her in French and she was smiling like the star of the picture – which she was in all her scenes with me. I was just there obscuring the view. Both in her two shots and in her close-ups photographed over my shoulder, she cheated her look past me to Mr Pabst, who was making love to her off-camera. Out of the funny complexity of this design Mr Pabst extracted his tense portrait of sterile lesbian passion, and Mme Roberts satisfactorily preserved her reputation.

Pabst took immense care over physical details. Louise Brooks, who was used to choosing her own costumes (Paramount had let her play a manicurist in a $500 beaded evening dress), found Pabst selecting everything – ‘from an ermine coat to my girdle’. His final victory,

which made me cry real tears, came at the end of the picture, when he went through my trunks to select a dress to be ‘aged’ for Lulu’s murder as a streetwalker in the arms of Jack the Ripper. With his instinctive understanding of my tastes, he decided on the blouse and skirt of my very favourite suit ... Next morning my once lovely clothes were returned to me ... torn and foul with grease stains. Not some indifferent rags from the wardrobe department but my own suit, which only last Sunday I had worn to the Adlon Hotel ... I went on to the set feeling as hopelessly defiled as my clothes. Working in that outfit I didn’t care what happened to me.

William Shawn, in his introduction, quotes a passage of which he says: ‘If she had written nothing more than that one sentence I would be prepared to call her a writer.’ It runs like this: ‘And so I have remained, in cruel pursuit of truth and excellence, an inhumane executioner of the bogus, an abomination to all but those few people who have overcome their aversion to the truth in order to free whatever is good in them.’ The Louise Brooks who no one in the Ziegfeld chorus line would share a dressing-room with might thus justify bitchiness. As the historian of her own art she delivers her truths with scornful finality. Of post-Gish, post-Garbo Hollywood, for example: ‘Producers were left with their babes and a backwash of old-men stars, watching the lights go out in one picture house after another across the country.’

Her mother, who ‘nearly always had more creative uses for her time than disciplining her children’, saw to it that Louise got dancing lessons. A college-student soda-jerk improved her Witchita vowels, and waiters her knowledge of food and cutlery. The chorus girl and dancer became an unwilling movie star – Hollywood could not offer professional satisfactions to match those of dancing. All the essays in the book add something to the theme of what artists did to fit themselves to Hollywood, or what Hollywood did to them. So when she writes about Bogart and W. C. Fields as stage actors, and about her own pleasure in being treated as an actress by Pabst, she gives a remarkable view of what it was like to be part of the film industry – one which serves to correct the views of critics who know the product but not the process of its making. She writes of the schoolboys in the Sixties who ‘approached me with wildly uninformed flattery ... presuming me to be a forlorn old actress full of gratitude’, and who expected her to supply material which they could ‘muck about with, sign with their names, and present to the teachers of their film classes’. She complains that ‘the Fields they idolised was the man they read about and superimposed on the Fields they saw (or didn’t see) on the screen.’ Yet her own narrative the autobiographical bits in these essays has many scenes which reinforce notions of Hollywood gleaned from the screen. She deplores a history of film in which ‘film celebrities cast themselves as stock types,’ yet neither her wit nor her intelligence, nor even her despair or her disgust, can make her story anything but a Hollywood one – which means it comes to us in a Hollywood mould. When she writes about Marion Davies’s niece, Pepi, the scene is set by memories of Citizen Kane – her real Hearst and Welles’s elide. When she describes how she got the news of Pepi’s death she makes a movie scene out of that too: ‘Dario and I opened at the Persian Room of the Plaza on 10 June 1935. The next day, John McClain telephoned ... Pepi had just killed herself by jumping out of a window of the psychiatric section of the Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles. Looking in the mirror as I checked my hair, make-up and costume for the dinner show, I thought, her dreaded visit to Hollywood had lasted exactly six weeks.’ Decades after the event she sets up the camera angle – over her shoulder, seeing her face in the mirror – before she says what she thought.

Hollywood, on her showing, was profligate with talent. Like a factory that packs lobster tails or goose livers and discards the rest of the beast, it took the bit that it thought it could best exploit. In Louise Brooks’s case it was a wonderful face. What never came to terms with Hollywood, and what Hollywood never had any use for, was the remarkable human being masked by it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.