The Other Half

Robert Melville, 4 July 1985

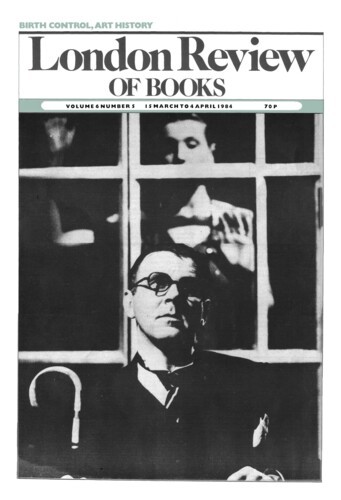

I knew Kenneth Clark by sight some time before he spoke to me. It was in the late Fifties, I think, at the press view of an exhibition of 20th-century English painting, that words were exchanged. We must have got there very early, because no one else was in the gallery. I was standing in front of a big Pasmore and Clark was coming to look at it. Suddenly I thought: ‘My God, he’s going to speak to me!’ ‘Am I right in thinking you’re Robert Melville?’ he said. ‘My name is Clark.’ ‘Indisputably, Sir Kenneth,’ I answered. I remember the word I used, because as soon as I said it I realised that it was ludicrously inappropriate. And I went on quickly: ‘It’s a fine Pasmore, isn’t it?’ He agreed. Nothing else was said, and we went our separate ways. I found it a pleasing example of his desire to get in touch with the people whilst looking down at us from a great height. We had three or four more meetings of a similar kind, at long intervals. I relied on news of him as a man, rather than as an art historian of unequalled readability, from Sidney and Cynthia Nolan, who went quite frequently to Saltwood Castle.