Against Whales

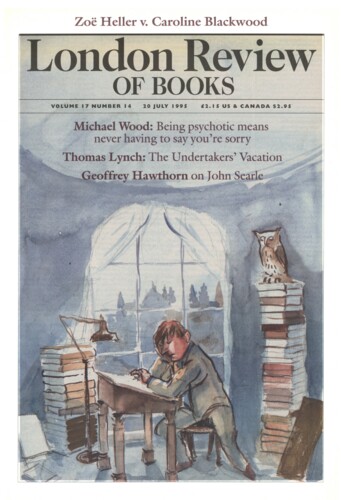

Paul Keegan, 20 July 1995

For Sir Thomas Browne it was a commonplace that ‘the number of the dead long exceedeth all that shall live.’ But this is no longer necessarily true, as has been pointed out in these pages before now: there may be more people living now than all the people who have ever died. With over 5.4 billion of us alive today, on course to become 8.5 billion by 2025, we must think of the outnumbering dead as outnumbered – at least until population slows (at perhaps ten billion, perhaps 15 billion) some sixty years hence.’