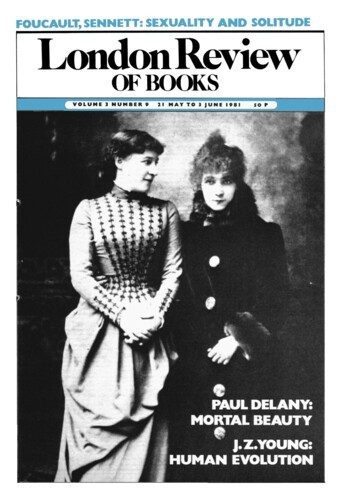

Mortal Beauty

Paul Delany, 21 May 1981

Nietzsche defined beauty as the highest type of power, because it had no need for violence. Here was a whole theory of beauty in a nutshell: but it is curious how little thought has been devoted to beauty since then, except as a rather anaemic branch of aesthetics. Unusual physical beauty, like unusual ugliness, is faintly scandalous: a product of chance rather than justice, it has typically been associated with stupidity, immorality and bad luck. This may be because beauty has been the only kind of social power monopolised by women; men have often felt resentment or mistrust towards it, but they have not been eager to examine their motives for doing so. A different way of dealing with beauty has been to praise it as the acceptable face of sex – a way of refining our animal urges, or displacing them upwards. But making beauty into a spiritual ideal often stems from uneasiness about its very concrete power to inspire action: an uneasiness that is pervasive in Kenneth Clark’s latest book.