Patrick McGuinness

Patrick McGuinness’s most recent collection is Blood Feather.

Colloquially Speaking: poetry from Britain and Ireland after 1945

Patrick McGuinness, 1 April 1999

Anthologies are powerful things: movements are launched, periods are parcelled up, writers are made and broken. They are, or want to be, the book world’s performative utterances: defining what they claim only to reflect, they make the things they speak of come to pass. But one last fin-de-siécle anthologising project remains: an anthology of anthology introductions. We would then be able to follow the growth not only of a market but of a genre, a genre with its own protocols and house rules, in which, much like poetry itself, the new product tussles with the predecessors it both rejects and feeds off. Such a book would show us the anthology in its many guises: the anthology as canon or as anti-canonical dry-run for a canon, as launching-pad or stock-take, as sampler or as revelation, as provocation or as consolidation. If, as Auden wrote, poetry makes nothing happen, then the poetry anthology has no such self-effacing qualms. Blake Morrison and Andrew Motion knew this, as did the predecessor they were tussling with, A. Alvarez’s The New Poetry (which was tussling with its predecessor, Robert Conquest’s New Lines). ‘This anthology,’ they wrote in their preface to the Penguin Book of Contemporary British Poetry, ‘is intended to be didactic as well as representative.’ Though the things anthologies make happen may be confined to poetry, the representative and the didactic are hard to tell apart.‘

Enlarging Insularity: Donald Davie

Patrick McGuinness, 20 January 2000

In a recent poem, ‘Languedoc Variorum: A Defence of Heresy and Heretics’, the American poet Ed Dorn honours Donald Davie’s penultimate collection of poems, To Scorch or Freeze (1989), as ‘the most economical rebuke … this age in moral free-fall is likely to get’. It is Davie’s most experimental poetry book: a series of religious meditations based on the Psalms (he edited The Psalms in English for Penguin) which take their bearings from Pound’s Cantos (he also wrote two ground-breaking books on Pound and numerous essays on the Poundian tradition). Dorn’s homage is apposite, too: his poem is founded on the conviction that heretics have been persecuted because they are, in fact, the only people who really care about religion, putting established cults to shame. Davie, a dissenter rather than a heretic, in religion as in poetry, had his fair share of polemical spats with what he called the poetry ‘establishment’: big commercial publishers and the metropolitan journals (the LRB gets a dishonourable mention in this category).‘

Going Electric: J.H. Prynne

Patrick McGuinness, 7 September 2000

‘Calme bloc ici-bas chu d’un désastre obscur’ (‘calm block fallen here below from some obscure disaster’): this line from Mallarmé’s ‘Le Tombeau d’Edgar Poe’ seems an apt description of his own poems – aftermaths of stellar catastrophes, meteors sitting impassively in their craters, enigmatic wreckage from some temporal or spatial elsewhere. But it would also do for J.H. Prynne’s poems, which contain lines like these, in ‘Star Damage at Home’, from the 1969 collection The White Stones:’‘

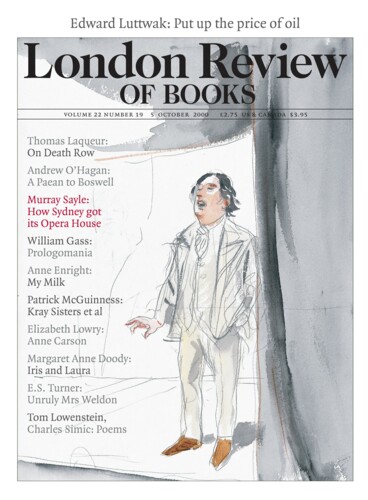

Get rid of time and everything’s dancing: Kray Sisters et al

Patrick McGuinness, 5 October 2000

Thetis, the mythical self-transforming nereid, could be the shape-shifting guiding presence behind these three books. Carol Ann Duffy and Jo Shapcott write poems about her, or more exactly through her, while transformation and metamorphosis, travel through time, space and states of being lie at the core of Gwyneth Lewis’s second English-language collection, Zero Gravity (her mother...

Pieces about Patrick McGuinness in the LRB

Book of Bad Ends: French Short Stories

Paul Keegan, 7 September 2023

Voltaire regarded the short tale as a duel with the reader, and a form of complicity. He went out of his way to disparage the ‘littleness’ of the form, and to ridicule all fiction, as fables without...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.