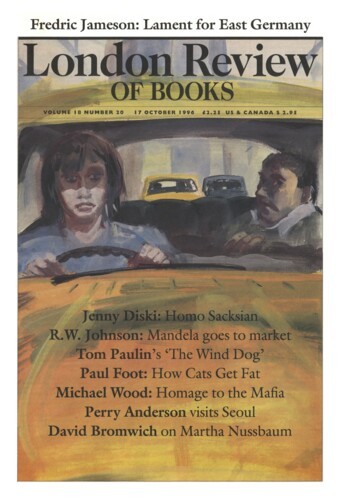

‘Did that man touch our car?’

Elisa Segrave, 17 October 1996

My name is Nicholas. I am 11 years old. I like plants because they have a different life to humans, and they are attractive. They can’t defend themselves and, instead of having blood, they have chlorophyll. They can’t move. They grow towards the light. I feel proud when my plants do well.