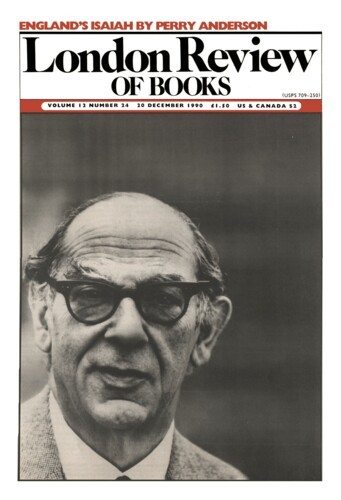

Putting it on

David Marquand, 12 September 1991

My favourite memory of Roy Jenkins dates from a golden July evening during the Warrington by-election. He is standing in the front garden of a council house, deep in conversation with an elderly Labour housewife, for whose support he is canvassing. Stooping slightly, and with a courtly gravitas that would not have seemed out of place at a European Summit, he is explaining why the ‘fluctooations’ which have characterised British economic policy for the last ten years have done so much damage to our international credit. The housewife is looking up at him with an expression of bemused, yet indulgent admiration, like an aged aunt applauding the exploits of a favourite nephew. In the background is a gaggle of SDP helpers, desperately trying to signal to the candidate that it is time to move on. It is clear that the housewife hasn’t the remotest idea what Jenkins is talking about, and that he hasn’t the remotest idea why his supporters are making faces at him. It is also clear that she is delighted to be talked to as though her opinions matter. Most of all it is clear that she will be switching her vote to him.