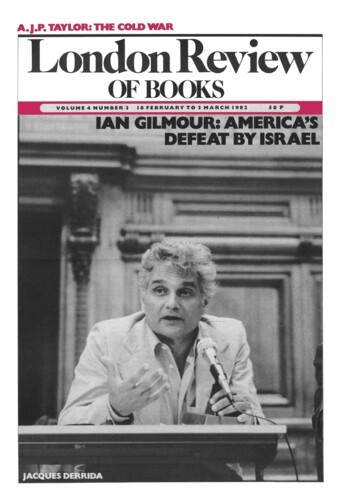

Deciding Derrida

David Hoy, 18 February 1982

Of the essays collected and excellently translated in Dissemination, the best example of Derrida’s own practice of the deconstructive criticism he fathered is ‘Plato’s Pharmacy’. Here he pursues his question why the metaphysical tradition from Plato to the present subordinates writing to speech. Derrida is not claiming to reverse Plato and to subordinate speech acts to écriture, intentions to texts. His suggestion is rather that the attempt throughout the history of philosophy to think about the relations of language, truth and reality is continually biased by the misguided oppositions between writing and speech, signifier and signified, the metaphorical and the literal, presence and absence, sense and intellect, nature and culture, or even male and female. For Derrida these dichotomies are set up not rationally, but with an implicit preference for one side or the other. His procedure for showing the prior exclusion of the other side is to study not the logic but the rhetoric used in such cases as Plato’s attack on writing, especially the metaphors and myths in the Phaedrus.