Vernon, Grandison, Caroline and Regent

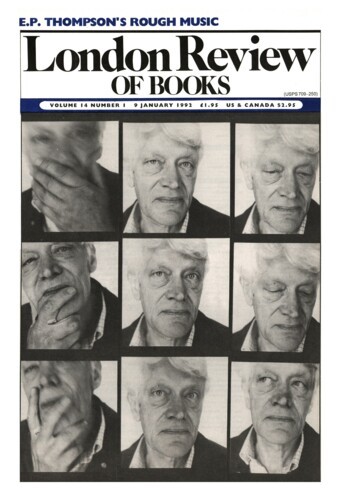

Alan Brien, 9 January 1992

Everybody, they say, has a book in them, if only the history of their lives up to their graduation from adolescence. I would agree, but with the proviso that these books be openly offered as fiction. When I think what unreliable witnesses my book chums are, especially about each other, I wonder how any trust worthy biographies, let alone autobiographies, ever get to be written. Most of these friends tend to dispute this thesis. But then, they would, wouldn’t they? For if they have not themselves been persuaded against their natural modesty and common sense to write autobiographies, flattered out of their natural caution and canniness to take on huge biographies, they will be reviewing the end-products, or perhaps supplying pre-publication quotes for the ads. At the very least, they are buying, or borrowing, or pretending to have read, the things.