At Bozar

Glen Newey

Why isn't there just zilch? It would have saved everyone a lot of bother, and you wonder why it never occurred to the Almighty. Creative artists, whose calling is to negate nothing by making something, can prove strangely drawn to inexistence – their own, if not the world’s in general. W.H. Auden found T.S. Eliot playing patience once, and asked him why he liked the game. Eliot said: 'Well, I suppose it's the nearest thing to being dead.' Painting seems to have done much the same for Francisco de Zurbarán, the subject of a major exhibition at the Bozar centre in Brussels until 25 May.

To a ‘religiously unmusical’ (in Weber’s useful phrase) Romeophobe, Zurburán’s Counter-Reformation imagery is often stupefying. Mariolatry is to the fore. Some of the paintings in the Bozar show seem, to a 21st-century eye, to ply the no man’s land between the kitsch and the surreal. In an Immaculate Conception, the Virgin is buoyed up on a cloud of disembodied infant heads, while beneath her a bunch of querulous-looking cherubs jostle and pore over plans. The same goes for St Francis in Ecstasy, and for numerous canvases where subjects warily eyeball the skies, as if being overflown by a flock of pigeons. Dalí’s debt to Zurbarán is as clear here as Morandi’s in the still lifes.

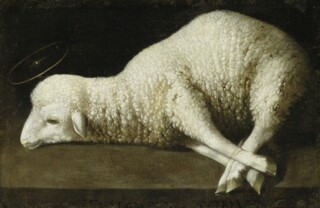

On the other hand, some pictures, like the bravura St Gregory, lend themselves to Zurbarán’s delicately realised treatment of fabrics, braids, calicoes, taffetas and brocade. There’s a charming one of Mary as girl asleep, and in general Zurbarán seems happier with docile or comatose subjects. The San Diego Agnus Dei lies, hooves trussed, as if airdropped without a parachute, a filament-like halo whizzing round its head like stars round a KO-ed Tom or Jerry. A couple of versions of the lamb by Josefa de Obidos, strongly marked by Zurbarán's influence, have the lamb in a similar pose on a slab that bears the tag: ‘occisus ab origine mundi’. It’s hard not to conclude that for de Obidos as for Zurbarán, dead is best, and, as the motto suggests, that things went bad from the get-go.

Despite himself, it’s in the room of natures mortes that Zurbarán almost comes to life, partly because it contains a couple of pictures by his son Juan. Fruit is wilfully succulent, the red-beaded flesh of a halved pomegranate, next to a frankly vulvar slashed medlar, a glimpse of licit sensuality. This is the work of Juan, who was borne off by bubonic plague aged 29. Alongside it, Zuburán père’s still lifes – an exquisitely rendered row of four ceramic vases, and baskets of apples and quince – remain just this side of astringent.

Zurbarán's clincher is the show's final canvas, a late (1660) crucifixion with a brush-and-palette-toting St Luke, patron saint of painters, at the foot of the cross. Unlike the show’s earlier eyeballs-skyward crucifixion, Jesus is here indubitably dead; Luke is caught in a rictus of maybe-grief maybe-ecstasis. Christ himself is pale, almost greenish under Bozar’s muted lighting. The specks of white and red paint on Luke’s board seem pathetically inapt for the task of limning the dead man-god that the picture itself shows. Here, at least, Zurburán has lighted on a subject of becoming tenebrosity. And an image of what Auden called ‘the dreadful martyrdom’ is, in its way, still life.