At the Whitechapel

Brian Dillon · Aspen

In August 1971 the US Postal Service wrote to Phyllis Johnson, the publisher of Aspen, an arts and culture quarterly then in its sixth year, to inform her that the magazine’s right to reduced postal rates had been definitively revoked. Aspen, which is the subject of an exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery until 3 March, seems to have fallen foul of Title 39 US Code 4354 on several counts, not least the journal’s increasingly intermittent publication schedule. There was the matter too of its eccentric form; whatever else it was, according to the Postal Service, a periodical was surely a discrete object made of printed sheets, bound together and maintaining more or less the same format from issue to issue. Aspen was a bureaucratically flummoxing proposition: an unpredictable agglomeration of essays and articles on loose pages or in booklets, packaged with flyers, photographs, diagrams, flexidiscs and even in one issue a spool of 8mm film – all housed in a box whose design and dimensions varied from one mail-out to the next.

In short, Aspen was scarcely a magazine at all; it was a work of art. Johnson, a former fashion editor, had started it with the ambition, as an advert in the New York Times declared, of surveying ‘all the ideas that enhance life, that make it meaningful and give it style and verve. Its coverage: everything that can be described as the civilized pleasures of living.’She named it for the Colorado ski resort that seemed ‘a symbol of the freewheeling life’. The intended or ideal readership, one of its editors said later, was ‘the Sixties’. Early issues are strewn with advertisements for upscaled-hip boutiques (‘Are you confused enough for Paraphernalia?’), articles on skiing and rather languidly campaigning pieces on environmentally threatened portions of picturesque America. Highbrow kicks came courtesy of the likes of Lionel Trilling (‘Cinema – the Andromeda of the Arts’), pop-cultural connoisseurship from a nostalgic essay on Dixieland jazz by Freddie Fisher. But Aspen quickly attracted notable guest editors who recast its cabinet-of-curiosities eclecticism in their own avant-garde images. Andy Warhol oversaw the third issue, with its ‘Fab’ cover graphics and flip-book version of his film Kiss. Quentin Fiore, who had designed The Medium is the Massage in 1967, put together a ‘McLuhan issue’ that also included a diary of more or less random pensées by John Cage, entitled How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse).

With the combined fifth and sixth issues, delivered in an austere white box like a giant cigarette pack, Aspen produced an artefact that was genuinely an addition rather than a deluxe adjunct to the art, literature and thought of the time. Brian O’Doherty, who had considered previous issues ‘interesting,but rather shallow intellectually’, corralled an astonishing number of works and writings by the US and European avant-gardes. There were texts by Susan Sontag, Michel Butor and Dan Graham,recordings by Marcel Duchamp, Alain Robbe-Grillet and William Burroughs, discreet artworks (or conceptual descriptions of potential artworks) by Mel Bochner, Sol LeWitt and O’Doherty himself. The lifestyle spreads had gone and the advertisements begun to dwindle, so white space and cool grids dominated: the whole, which is also a sort of exhibition, is a key document in the transition from Minimalist art to text-heavy Conceptualism. O’Doherty asked Roland Barthes for an essay, and he gave him ‘The Death of the Author’, previously unpublished. (Barthes never got paid, despite letters and postcards asking where his fee was that are included in the Whitechapel show.)

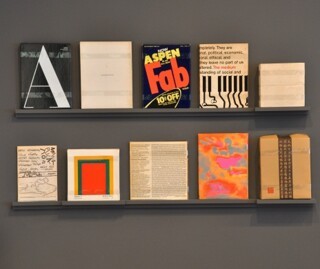

At the time of writing, a slightly battered example of Aspen no. 3 signed by Warhol will set you back $22,500 on AbeBooks. (Unsigned you can get it for $1500, andthere’s also the whole run minus no. 10 for $9450.) The relative ease with which one can still get hold of the magazine is a little surprising, because the mythology attached to Aspen consists partly in its supposed rarity: O’Doherty has noted that readers were as perplexed as the Postal Service, and most issues were probably thrown away. At the Whitechapel, all ten numbers –publication stopped in 1971 – are tantalisingly vitrined, and there’s an accompanying display of other magazines-in-a-box. McSweeney’sadopted the model of a dispersed periodical in 1998, and for the past decade Cabinet (where I’m an editor) has attempted some ofits Wunderkammer mix of essays, artists’ projects and paper ephemera. Aspen itself is among the star items on UbuWeb – Kenneth Goldsmith’s vast and frequently copyright-flouting collection of artists’ texts, films and audio – where its immaterially archived fragments continue to inspire writers and artists still committed to words on pages and actual objects.

Comments