In the Saddle

Alice Spawls

As the first signs of autumn began to appear last week I went horseriding with my sister in Trent Park, just north of London. It's mostly woodland, and for a lot of the time you can go without hearing or seeing another person, or car or any sign of modernity, even though it’s only a couple of miles from the M25. When you’re alone you can ride as fast as you like, which is to say as fast as you can, feeling the earth kicked up behind you, the forest a blur, the burn of little branches whipping you in the face. The horses we ride are only stable cobs, but the fantasy horse is always an Arabian.

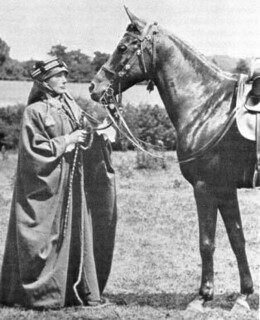

The Horse: From Arabia to Royal Ascot, at the British Museum until 30 September, traces a history from domestication more than 5000 years ago to modern racecourses, through rock paintings, ceremonial tack, carvings and pictures. The Arabian was first introduced to British equestrianism in the 18th century. In the 19th century, the poet and adventurer Wilfrid Scawen Blunt and his wife Anne (Byron’s granddaughter) started an Arabian stud at their estate in Sussex, travelling to the Middle East to find pureblood horses to bring back to England.

Wilfrid thought Anne ‘drab’ (it wasn’t a love match) but she had been taught drawing by Ruskin, spoke various languages and, he later admitted, 'there was no one so courageous as she'. They travelled for six months at a time, to areas unknown to Europeans, visiting Bedouin communities on horseback and camel. The first mares they brought back were named Dajania, Hagar, Jerboa, Wild Thyme, Burning Bush. They both became fluent in Arabic and Anne translated two volumes of Arabic poetry, as well as publishing her revised diaries of their travels.

In A Pilgrimage to Nejd, Wilfrid described visiting the Bedouin of Jebel Shammar as 'an almost pious undertaking... a pilgrimage'. He admired what he perceived to be their religious and political simplicity, the 'shepherd rule' which he thought offered 'a community living as our idealists have dreamed... without compulsion of any kind, whose only law is public opinion and whose only order a principle of honour’. Edward Said wrote that Blunt, like other Oriental experts in England and France, ‘believed his vision of things Oriental was individual, self-created out of some intensely personal encounter with the Orient, Islam, or the Arabs’. But Said also singled Blunt out for not expressing ‘the traditional Western hostility to and fear of the Orient’.

He was determined to help emancipate the Arabs from Ottoman domination. After the defeat of Ahmed Orabi's rebellion in Egypt in 1882 (Blunt considered Orabi a protégé), Blunt turned against the occupying British, and British occupation everywhere – he was the first Englishman to be sent to prison for supporting Irish home rule (in 1888) and campaigned for a seat in Parliament on that platform while he was in prison. Oscar Wilde reviewing his book of poems the following year said that ‘prison has had an admirable effect on Mr Wilfrid Blunt as a poet.’ He did not, however, win the election.

The couple split in 1906 after Wilfrid tried to move his mistress in with them. They divided the horses. Anne retired to Egypt and their second stud farm, Sheykh Obeyd; after her death (and a bitter legal battle with Wilfrid) their daughter Judith ran the English stud. Today more than 90 per cent of Arabians are descended from the Blunts’ horses.