Heath Ledger

David Thomson

The entry on Heath Ledger was inadvertently dropped from the fifth edition of ‘The Biographical Dictionary of Film’, out next month. It will be included in the sixth edition. In the meantime, here it is.

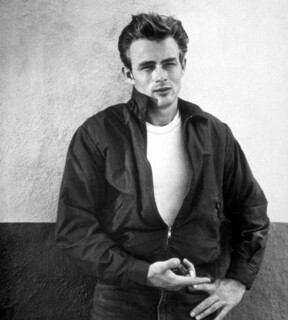

Heath Ledger was only 28 when he died, so he was four years older than James Dean at that unexpected moment. Yet he feels less of a loss than Dean. Unless you loved Ledger, and only love inspires true loss. Perhaps we have to admit that no one now really loves movie stars as people did when Dean died in 1955. But if Dean had lived – he’d be close to 80 – would all of us have become dismayed by a boredom that settled on him? Isn’t that what happened with Brando? I don’t mean Brando was boring in person, but he had wearied of being Marlon Brando and lost faith in acting and pretending.

Actors don’t lodge in the culture as once they did. They are a type of celebrity now. If a young soldier from Duluth or Wolverhampton is blown up in Iraq, the news passes swiftly. The names don’t linger. But if the young man was Prince Harry or a Kennedy grandchild then it would be news of a different order. Fame (with or without achievement) has a brief purchasing power on our attention and then it is replaced. Remember River Phoenix? Just. Most of you were not alive when James Dean died, but you know who Dean was. You have seen his films and you can make the imaginative jump that grasps something of what his death meant.

Then take Robert Williams. He was an actor who made half a dozen pictures, including Platinum Blonde (1931), a Jean Harlow movie. There’s no need to go into it in depth (and you can find the film), but Williams is ‘extraordinary’ and ‘brilliant’ in Platinum Blonde. I’d add ‘memorable’ – but so few of us remember him. He died of peritonitis before the film opened. He might have been another Cary Grant – but so might Cary Grant.

What I’m trying to convey is that the question of how good an actor Heath Ledger was is less interesting (or open to answer) than why we ask ourselves such questions. His last film was The Imaginarium of DoctorParnassus, a Terry Gilliam picture. So it was easy to credit that Ledger would be original/striking/funny/sinister/unpredictable (select two) in the picture, even if a few other actors had to complete his work, but that he might be kept from considerations of acting genius by the frolic and froth of a Gilliam picture. It was always easier to win an acting Oscar in an Elia Kazan picture than in one directed by Jerry Lewis, Preston Sturges or Terry Gilliam. Kazan came on in a boxer’s crouch that said: ‘Look, I care about acting. I really care.’ That’s the great start Dean got in East of Eden – his Cal is so placed and framed that the entire picture says: ‘Look at him.’ If you doubt that, just consider the way Cal’s brother is treated. Try to remember the name of that actor, or even the name of the brother!

On one occasion, at least, a picture opened like the waves of the Red Sea to reveal Heath Ledger. I’m thinking of Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain, from the Annie Proulx story, though clearly that attention was not just on Ledger but on Jake Gyllenhaal, too, as the other cowboy. Ledger was very good in that film and a surprise, for he had not shown such depth or calm before. It wasn’t just that he made us believe in a ‘gay’ cowboy. He made us think of an Ennis Del Mar who had the limited world view of a Wyoming cowhand. In short, he was playing someone a good deal less educated or worldly than Heath Ledger – and many actors are not comfortable playing ‘dumb’.

But I never lost some feeling with Brokeback of watching an actor attempt a tricky role, and it is possible that that owed something to Ledger’s caution at playing a gay character. So, despite the quality of the writing and the alertness of Lee’s direction, I felt I was watching two actors not two cowboys.

I found it easier to ‘lose’ myself in his Joker in The Dark Knight. Much of that performance lay in the dazzle of the make-up and the showiness of the director’s style. It didn’t help Ledger in a key moment (where he threatens Maggie Gyllenhaal’s character) that the camera insisted on whirling around the two of them while Ledger’s authority begged for stillness. The most interesting thing about that film was his voice and his way with words. That’s where Ledger began to open up the chilly, demented humour of the Joker and its wounded philosophy. A lot of acting in films is being watchful, and waiting and listening. Ledger won his Oscar when the Joker talked and a warped mind flowered.

After his death (a few months before The DarkKnight opened), it was impossible to extricate Ledger’s personal story from the box-office performance of the picture. Sentimentality weighed in and most pundits guessed Ledger would win the supporting actor Oscar. His competition was not intense – his one real rival, Michael Shannon in Revolutionary Road, might have said, with justice, that he really was a supporting actor while Ledger was a masked lead. But silly things happen at the Oscars, and although the feelings of loss at Dean’s death were greater than they were for Ledger, Dean never won an Oscar. Should he have won? Why ask that futile question? Ledger knew that all actors should win, including those who don’t get the good parts, including those you have never heard of.

It’s a game to ask ‘What would have happened?’ with Heath Ledger. But it’s an instructive game. Imagine you are Heath Ledger. Think of the films that have opened in the time since he died. Which would you have wanted to play? Milk? No, I think we know why Ledger turns that down. BenjaminButton? Are you kidding – that’s not a part, it’s a burial. Revolutionary Road? Possibly, but in truth Kate Winslet needed an older man. And later films? Public Enemies? Nothing there. Funny People? Now, that’s an interesting question. ‘The Joker Jokes Again’? No, they never made that, but they might have done if Ledger had lived though it sounds like as dead an end as death.

That’s the lesson: actors can only choose from things offered to them, and often it is impossible to know how a role will develop. Actors are at the mercy of the public and the medium. Do you realise how long it took for America to realise Cary Grant might be the best actor the movies had ever had? Until a few years before he died. I talked to him a couple of times in that period, and I don’t think he was ever persuaded of how good he was. He was intimidated and haunted by that other fellow, Cary Grant.

Actors can be destroyed by success and failure. Think of Mickey Rourke – so cute, so quick, so sly, so promising in Diner, Body Heat, Rumblefishand a few other things. Then he got taken over by the armoured idea of ‘Mickey Rourke’ (rather in the way the human being in the Joker has been hijacked by the make-up and the image). So Rourke trashed himself for years and brutalised his own face and body. He made The Wrestler, but only as the wreck of that notorious celebrity ‘Mickey Rourke’. He isn’t an actor anymore – as in live pretending. His creative reality is gone.

Or think of Brad Pitt. There was a moment when Pitt was as electric as Rourke. It was the time of Thelma &Louise, A River Runs Through It and Kalifornia. It lived on in Se7en and Fight Club. But see what has happened! Pitt has been overwhelmed by spurious celebrity and dreadful star parts – all those stupid Ocean films, not to mention Button, the Tarantino travesty and so many others.

Not that a Pitt could take comfort from the general pattern of what happens to our great actors. If you want to propose Pacino, De Niro and Nicholson as the outstanding figures of the 1970s and 1980s, they have become pastiches of what they once were. They might agree with Nicholson – that the damn picture business doesn’t supply you with decent parts as you grow older. All of which makes the continuing efforts of a Meryl Streep to find good roles a marvel. But Streep may be brighter than the guys, and more modest in her financial demands.

Early death is regarded as a tragedy, but for actors it may be a mercy. What was Valentino going to do if he had to talk? How would that posturing lothario speak? Dean died with three performances in the bag that transcend disappointment. We know now that Marlon Brando made his best films at the beginning. This wasn’t just the particular films he had. It was his need and innocence. As time went by, Brando fell out of love with himself and with acting. You have to wonder what a Pacino or a De Niro now would say about this plight.

So Heath Ledger was a young hunk, with some pride and panache. He’s watchable in The Patriot, Monster’s Ball and Casanova, and helpless in many other things. In two films, he is seriously interesting, and in one he has moments of greatness. That’s not an unkind verdict, or unfair, and it would fit Robert Williams and the thousands of kids who know they have it in them to be a great actor – if they had Shakespeare, Kazan to direct, Anthony Hopkins as Claudius and Streep as Gertrude. They could have been Hamlet, a contender. That cry of longing hangs over the history of acting. And so wave after wave of young people abandon their own real lives in the pursuit. They begin to be dead, or legendary, and they reckon the trade is worth it.