I don’t remember when I was first irritated by that children’s rhyme, which is wrong twice over. Oil painting may well be hard but in some ways it’s easier than painting in watercolour, and watercolours are often more beautiful. However, the prejudice the rhyme encapsulates does arise from real differences. A typical oil painting is an object, a substantial piece of work displayed on a wall. Its colour is strong, the paint may be thick, may even stand proud of the picture surface. A watercolour remains firmly in its two dimensions, is often not intended for a wall and may be a topographic or scientific document. The colour is less strong and the paper it’s painted on plays a greater part in what you see than canvas does in an oil. Watercolour paints and paper are cheaper, and more portable. Historically, it has been a medium for amateurs, women, children and travellers, for miniature painters and manuscript illustration, for preliminary sketches and notes, or for the precise delineation of plants, buildings, landscapes and animals. When watercolour painters, who were at various times excluded from Royal Academy exhibitions, wished to establish their art as an alternative to oil painting – one of equal (if distinct) aesthetic merit – they were caught in a bind. The more heavily or intensely worked, the more like oil paintings their pictures became, and the greater the possibility that the fresh truth of passing effects, which was the medium’s strength, would be lost. That quality had been developed in England to a high degree.

In Watercolour (at Tate Britain until 21 August), there are many examples of that freshness: two of the most famous, Thomas Girtin’s The White House at Chelsea and Turner’s Blue Rigi, hang side by side. There is also Bonington’s view of the Piazza dell’Erbe in Verona, which gives a sense of moving crowds and shifting light that makes Canaletto’s Venetian crowds and calm yellow sunshine seem mechanical. Sargent’s picture of a crashed aeroplane with harvesters in the foreground, painted in France in 1918, has the gawkiness of something noticed, not composed, while in David Cox’s Tour d’Horloge,Rouen it is not so much the architecture of the clock tower as the patch of bright light seen through the arch at its base that is the subject. This kind of observation, centring on light, weather and landscape, became a distinguishing characteristic, not just of swift accounts made on the spot but of elaborately stippled, highly detailed studio pictures like Alfred William Hunt’s meteorologically exquisite November Rainbow or the gaudy sunlit foliage in Myles Birket Foster’s Burnham Beeches.

However, much of the work in the exhibition is not of this kind. By taking the medium all the way from the Middle Ages to the present day, and by excluding no substance (gouache, acrylic, earth even) that can be diluted in water and fixed, the exhibition is able to include manuscript illustration from the 13th century at one end of the timescale and two twigs attached to the gallery wall and painted with gouache by Hayley Tompkins at the other.

The show includes things made for a practical purpose. An estate map of 1582 has its carefully surveyed fields differentiated into crops and grazing; while Hollar’s views of the defences of Tangier, c.1669, are an early example of watercolour being pressed into military service. Drawings of plants – an asphodel by Georg Ehret and an orchid by Franz Bauer – are wonderfully precise and sufficiently free from the imperfections of individual specimens to stand as scientific botanical descriptions.

The staccato effect of contrasting periods and genres is less comfortable when works are assembled to illustrate themes – ‘Watercolour and War’, ‘Watercolour Today: Inner Vision’, ‘Travel and Topography’: any one of these themes would be worth an exhibition on its own, as would many of the individual painters. One could almost wish for the abundance of the 19th-century exhibitions, where pictures were hung close-spaced in ranks.

The section labelled ‘The Exhibition Watercolour’ shows what happened when the medium took on oil painting head to head. White paper disappears, subject matter becomes more dramatic. Here you have Turner’s mountain landscape The Battle of Fort Rock, Val d’Aouste, Arthur Melville’s The Blue Night, Venice, in which a luminous sky of midnight blue is as much the subject as the campanile that reaches up into it, and Burne-Jones’s The Merciful Knight. John Frederick Lewis, who spent ten years in Cairo amassing drawings of Oriental life, came home and turned them into images like Hhareem Life, Constantinople, in which the detail is abundant and accurate but the atmosphere suburban English. In the end he gave up watercolour; there was more money in oils.

There is much enjoyment to be had from seeing what can be done with a loaded brush and from studying how the artist controls the bleeding of one colour into another. Indeed, in the hands of artists from Turner to Patrick Heron (his gouache abstracts are quite as successful as oils in the same mode), this might seem to be the proper pleasure to take from the watercolour. The precise kind of watercolour drawing which depicted every crocket on a cathedral façade also had its progeny, however. Pictures of such buildings by Cotman, with their flat mosaic of patches of colour, also evident in his watercolours of seas and heaths, came to be much admired in the 20th century. Francis Towne’s mountain landscapes pleased Eric Ravilious, whose versions of hills and sea taught people to understand the pale boniness of the South Downs. In Soldiers at Rye of 1941, Edward Burra, a painter of big, neat, surreal watercolours (the largest of any shown in the exhibition), no doubt because he was allergic to oil paint, makes a threatening version of the same shapes by following the contours of bulging buttocks and calves and the carnival masks of soldiers. Late in life he too turned to landscape: in a Northumberland valley here an oppressive hillside looms, as dangerous as any soldier. It is not imagined (his sister, who was driving him at the time, recalled a valley ‘south of the Cheviot’), but it has the floating, threatening topography of a dream – something watercolour does well. The figures swimming away from you in Blake’s The River of Life could be inhabiting one of those dreams in which you glide gently above the ground.

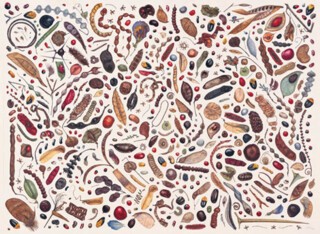

When it comes to the present day one is back with exhibition art. There is a recent example of botanical illustration (Rachel Pedder-Smith’s Bean Painting: Specimens from the Leguminosae Family), but on the whole the curators have turned to fashionable modernity to bring things up to date. The odd example from a body of work like Arthur Lockwood’s, which records disappearing industries in the Midlands and is as exact and informative as Hollar’s fortifications (more useful than photographs: drawing interprets as well as represents), would have established a continuity with the practical records that are the exhibition’s starting point. Edmund Dulac’s illustration to The Entomologist’s Dream and Aubrey Beardsley’s Frontispiece to Chopin’s Third Ballade are included, but there is no recent illustration. The pieces shown have moved a long way from the traditions that inspired the bulk of the exhibition.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.