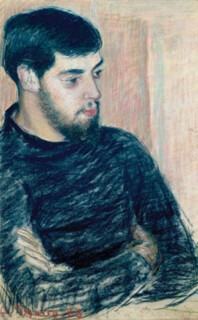

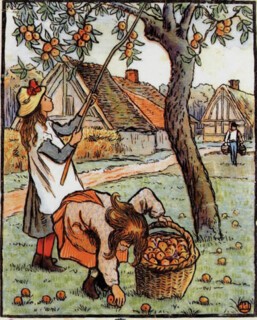

Camille Pissarro, the great Impressionist painter, spent a year in England escaping from the Franco-Prussian War. His eldest son, Lucien, spent more than half his life here. Lucien was the gentlest, sweetest, least practical of men, it seems. His wife, Esther, the tough one, had two goals, the art historian John Rewald wrote: ‘to make friends happy while at the same time running his life by any means she could think of’. Together she and Lucien produced the 30-plus books printed by the Eragny Press, the subject of the current exhibition at the Ashmolean (until 13 March). Lucien Pissarro in England: The Eragny Press 1895-1914 is about as good as such a show could be. It has all the Eragny books, several in multiple copies so that more than one spread can be seen. The books were mainly small, sometimes printed in red and black, though more often reproduced from colour wood engravings; some were traditional tales for children, some were by living writers; the texts were set close, often within flowery borders, the engravings ranged from peasant children in his first book, The Queen of the Fishes, to Italianate girls in long dresses in a Perrault fairytale.

The exhibition goes beyond the production of books. It includes three of the pictures Camille painted from the windows of the house in Bath Road, where he stayed with Lucien and his family in 1897. (His French views of England’s new suburbia have a lightness no native painter attained.) Lucien had just suffered a cerebral haemorrhage; he was young (born in 1863) and made a recovery, but lost some use of his left leg and arm and, perhaps, some of his confidence as a painter. His concentration on book-making and engraving during the next two decades, and the retreat from avant-garde adventures (he had experimented with Pointillism), may have been a result. When he returned to painting in the last decades of his life he reverted to the Impressionism of his youth.

Adjacent rooms that contain the Ashmolean’s collection of Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, Sickerts and Camden Town paintings, perhaps because not a stunning collection like the Courtauld’s, make one think about what less wealthy English collectors could afford and of painters aspiring to fill smaller walls. Walls not necessarily much more extensive than those the Pissarros lived within. Simon Shorvoan’s essay in the catalogue describing their lives in England is a vignette of Bedford Park bohemia, of dedication to an artistic life in which poverty was an accepted condition. The dilapidated 18th-century cottage, The Brook, which Lucien and Esther moved into in 1901, was over the years transformed into what Tyrone Guthrie called ‘the prettiest house in London’ and the books were part of it. At times the family was so poor they had to rent it out and live in the studio annex (Alec Guinness was one tenant). ‘Low, small, with four deep windows in which were all kinds of flowers’, a Dutch visitor wrote.

On the walls paintings by Camille Pissarro, Lucien Pissarro and others. The dining-room is even smaller. When you sit down there is no room left. On the walls old Japanese woodcuts, engravings by Dürer, Ricketts and Pissarro. Above the fireplace are shelves of well-read books – apparently quite extraordinary books to judge by the title. Madam is very sweet, yet very cultured. Pissarro, hidden behind his beard and thick eyebrows, sat there enjoying everything so heartily and yet so quietly.

There is something French in all that, as though scrunched up here was a condensed version of the famous dining-room at Giverny (Esther corresponded with Monet about gardening).

There are volumes from other private presses in the exhibition – Doves, Vale, Kelmscott, Ashendene. Only the Eragny books mix French modernity, English antiquarianism and the Pre-Raphaelitism that Camille Pissarro feared would corrupt his son’s naive talent. The books from Doves Press, severe, unillustrated, seem to imply a different way of life from Pissarro’s with their colour, decoration and engravings, not only of the Italianate girls his father disliked but also the odd peasant who might have a relation in a Millet drawing. Yet the Arts and Crafts ideal of things well made and serviceable could easily lapse into a kind of luxury that seems foreign to its intentions. The Doves Press books – volumes of Shakespeare, the Bible, Milton: not hard texts to come by – were monuments to literature. The Eragny books ask that you turn their few pages: the Doves books rest in hermetic magnificence while you read the paperback. In his introductory note to the Kelmscott edition of Ruskin’s The Nature of Gothic William Morris proudly states that Ruskin didn’t just ‘let a flood of daylight into the cloud of sham-technical twaddle which was once the whole substance of “art criticism”’: he had ‘done serious and solid work towards that new-birth of Society, without which genuine art, the expression of man’s pleasure in his handiwork must inevitably cease altogether and with it the hopes of the happiness of mankind’. Think of Ruskin in Brantwood, even of Morris at home, and the cosiness of The Brook takes on its own moral quality. The Pissarros were anarchists, of the most pacific kind: active socialism was more demanding.

Lucien’s first attempts at book-making were for children. Had he become a professional illustrator such as Walter Crane or Kate Greenaway penury would have been avoided. But though he admired Charles Keene’s observation of types and was encouraged and helped by Ricketts and Shannon there was too much of his father’s son in him, and not enough of the English craftsman, for him to become a professional illustrator, working for publishers in the English manner. The English tradition made wood engraving a natural medium. To print text and pictures together by the same process gave an aesthetic unity that was at the time much admired in 15th-century models like the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, which Ricketts and Shannon imitated. Later presses like the Golden Cockerel continued the tradition well into the last century, often taking their inspiration from illustrators like Thomas Bewick. The move was towards books that were more readable, less monumental, plainer.

In France things were different: the mix of type, lithography and etching, as well as woodcutting, resulted in wonders of freely drawn illustration. In 1900, while Pissarro was producing little books of Flaubert stories with wood-engraved frontispieces and borders, Verlaine’s Parallèlement with Bonnard’s sensuous, sprawling illustrations was being published in Paris. Verlaine’s was a ‘livre d’artiste’, another category of book too grand to read.

The asymmetry of the exchanges between England and France which the exhibition and the Ashmolean pictures represent gives the relationship between the two its character. The English responded to Impressionism’s escape from the academic into the everyday, but made something tighter and darker of it. The French pleasure in picnics and river parties and weather wasn’t naturalised here. Between the wars Pissarro was close to Charles Ginner, Robert Bevan, Sickert, Spencer Gore, painters well represented in the Ashmolean. There is a pleasing primness about them, a neatness, a care about getting the drawing right, that was just what Camille hoped Lucien would escape from.

In 1947 Pissarro’s widow and her nephew buried the Eragny types at sea as they made their way back to France. Having a typeface cut for your press was a crucial rite of passage, but when the work of the press was done, destroying the types and punches saw to it that your types would grace no corrupt version of your style. Cobden-Sanderson dropped the Doves Press types and punches into the Thames off Westminster Bridge.

The exhibition’s catalogue is admirable. Private press books from the end of the 19th century are unlikely ever to become a popular taste but one turns its pleasing pages wanting the many things one learns from it about the relation between art in France and England to be helped through it to a less obscure place in the world. An awkward offspring one would like to see appreciated.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.