Gwen John’s attic bedroom, Edward Hopper’s Sun in an Empty Room, Adolf Menzel’s open window and blowing curtain, Andrew Wyeth’s New England rooms full of cold, hard light, Hammershøi’s frugal Danish ones and Van Gogh’s narrow bedroom: these are pictures you might choose if exiled to a desert island. Thinking of the inviting effect such paintings have I went looking for them in the National Gallery. The closest thing I could find was Hammershøi’s 1899 Interior, in which there is a figure – a maid – but she has her back to you.

Why so few? It may just be that painters didn’t feel a picture without a figure was complete, but whatever the reason, the unpeopled room is a late subject. Unpeopled landscapes are rare too, but the tradition of outdoor sketching, as much note-taking as picture-making, goes further back: a glance round the room you worked in might be enough when it came to remembering the fall of light from a window, but without a sketch made out-of-doors the look of morning mist, high clouds or the colour of distant hills may be lost. Most oil landscape sketches – those from the Gere Collection, for example, that share a little room in the National Gallery with wonders like Corot’s Avignon from the West – were not made to be exhibited.

Pictures of empty rooms are also different from landscapes in that they suggest private places, but ones which, because they are empty, you are tempted to enter. In Gwen John’s attic you are alone, waiting for someone; in Hopper’s empty room you attend on the realtor who will draw up in his car any moment now. Sometimes, finding yourself alone in a room, if only fictively, you wonder what kind of life is, or could be, lived here. Novelists put characters in rooms that give colour to their thoughts. Henry James does it memorably in the first paragraph of The Wings of the Dove:

She waited, Kate Croy, for her father to come in, but he kept her unconscionably, and there were moments at which she showed herself, in the glass over the mantel, a face positively pale with the irritation that had brought her to the point of going away without sight of him. It was at this point, however, that she remained; changing her place, moving from the shabby sofa to the armchair upholstered in a glazed cloth that gave at once – she had tried it – the sense of the slippery and of the sticky. She had looked at the sallow prints on the walls and at the lonely magazine, a year old, that combined, with a small lamp in coloured glass and a knitted white centre-piece wanting in freshness, to enhance the effect of the purplish cloth on the principal table; she had above all, from time to time, taken a brief stand on the small balcony to which the pair of long windows gave access. The vulgar little street, in this view, offered scant relief from the vulgar little room; its main office was to suggest to her that the narrow black house-fronts, adjusted to a standard that would have been low even for backs, constituted quite the publicity implied by such privacies. One felt them in the room exactly as one felt the room – the hundred like it, or worse – in the street. Each time she turned in again, each time, in her impatience, she gave him up, it was to sound to a deeper depth, while she tasted the faint flat emanation of things, the failure of fortune and of honour.

Rooms not unlike that one are the background against which the Camden Town painters displayed life. They have more character than the inn rooms and kitchens carved by the light from small windows and open doors in 17th-century Dutch genre paintings, whether low-life scenes by Teniers and Ostade or the ordered rooms in which ter Borch’s ladies and gentlemen exchange notes, play music, or pose. It is partly a matter of what light is used for. When it spotlights brawling drinkers or caresses satin skirts and fur collars the economy of looking that determines the path of the eye means that less time is spent on the room, more on the people and their clothes. If the light is spread evenly and the figures have their backs to you or are concentrating on a task – in Vermeer’s case, pouring milk, weighing gold or making music, in de Hooch’s looking for nits in a child’s head or taking a basket of apples from a boy – it is easier for the viewer to share their space. You feel that they would be too self-absorbed to notice you.

There are pictures in which rooms are something more than backdrops. In Danloux’s Baron de Besenval in His Salon de Compagnie, the ormolu-mounted Chinese pots that crowd the chimney piece and the paintings that fill the wall hold your attention more than the baron’s unemphatic profile. But nothing in the National Gallery has the same snapshot-like acceptance of accidental detail as Købke’s portrait of his friend Frederik Sødring in the Hirschsprung Collection in Copenhagen, in which light falls equally on the panelled wall, the prints pinned up on it, a pot of ivy and the sitter. The National Gallery’s picture by Liotard of a lady pouring chocolate comes closer to it: the room is modest, there is rush matting on the floor, on the wall there is one of those plain Dutch church interiors. It comes to you that when you can see a sitter’s feet – you can see both the baron’s and the lady’s – the view is wide enough to let you in. A room can be set up as a commentary on people and their doings. If you scan the scenes in Hogarth’s Marriage à-la-Mode you find little caricaturist’s jokes: the grotesque frogs and figurines above the fireplace in the Tête à Tête, for example, that somehow stand as evidence of the decadence of the bored, hungover couple slumped and yawning below. This is a room you don’t step into.

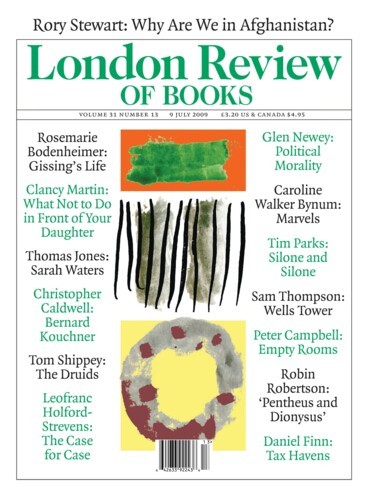

There is a long history of architectural perspectives of interior spaces, real and imagined, that runs from the columned gallery and inlaid pavement of Piero’s Flagellation through Saenredam’s pale Dutch churches, Pannini’s theatre galleries and palaces (the National Gallery has his interior of Saint Peter’s) on to Gandy’s views of John Soane’s buildings, whether occupied or empty, and any number of paintings, mostly in watercolour, of 19th-century grand houses. These are not pictures of rooms that invite you in. Minor pictures, I now realise, are more likely to welcome you into their rooms. Matisse, Bonnard, Bacon; you can conjure up rooms from each of them, but you can’t slip in – you don’t even want to.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.