1 January 2003. A Christmas card from Eric Korn:

This is the one about Jesus

And his father who constantly sees us

Like CCTV from above

But they call it heavenly love;

And the other a spook or a bird

Or possibly merely a Word.

Rejoice! We are ruled thru’ infinity

By this highly dysfunctional Trinity!

10 January. In George Lyttelton’s Commonplace Book it’s recorded that Yeats told Peter Warlock that after being invited to hear ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’ (a solitary man’s expression of longing for still greater solitude) sung by a thousand Boy Scouts he set up a rigid censorship to prevent anything like that ever happening again. This is presumably the origin of Larkin’s remark that before he died he fully expected to hear ‘They fuck you up, your mum and dad’ recited by a thousand Girl Guides in the Royal Albert Hall.

12 January. Read Macbeth for maybe the second time in my life (and I don’t think I’ve ever seen it). Much of the language is as opaque as I generally find Shakespeare but I’m struck by how soon he gets down to business, so that within a scene the play is at full gallop. No messing about with Lady M. either. No sooner does she learn Duncan is going to visit than she decides on the murder. Oddities are Macduff’s abandonment of wife and family in order, seemingly, to save his own skin, though the scene in which his wife is discussing this with Ross is unbearably tense, the audience knowing she is about to be murdered. The ending is as abrupt as the beginning, with not much in the way of a dying fall from Malcolm, who’s straightaway off to Scone for his coronation. Most relevant bit:

Alas, poor country,

Almost afraid to know itself . . .

. . . where violent sorrow seems

A modern ecstasy.

14 January. When I am occasionally stumped on a grammatical point, having no English grammar, I consult a copy of Kennedy’s Latin primer, filched more than thirty years ago from Giggleswick School. It’s only today that I notice that some schoolboy half a lifetime ago has painstakingly converted The Revised Latin Primer into ‘The Revised Man Eating Primer’. Perhaps it is the same boy who has inscribed across one of the pages: ‘G.H. Williams, Lancs and England’.

22 January. Watching Footballers’ Wives I see among the production credits the name Sue de Beauvoir.

I do so hope she’s a relation.

1 February, Yorkshire. Last time we visited Kirkby Stephen we were in Mrs H.’s shop when a clock chimed. I’ve never wanted a clock and this one was pretty dull, made in the 1950s probably and very plain. But the chime, a full Westminster chime, was so appealing that we talked about it on the way home and later asked Mrs H. to put it on one side. Today we collect it and it looks every bit as dull as we remember, but now on the table behind the living-room door it seems very much at home. And the chime is of such celestial sweetness that when it goes it’s hard not to smile.

9 February. To Widford in the Windrush valley near Burford for a second look at the church built on the site of a Roman villa, the mosaic floor (now covered over) once the floor of the chancel. There are box pews, aged down to a silvery grey, a three-decker pulpit, Jacobean altar rails and the remains of whitewash-blurred medieval wall-paintings. It’s an immensely appealing place, not unlike Lead in Yorkshire or Heath near Ludlow. Good graves on the north side, some for a family called Secker who seem to live in the manor house across the field, a romantic rambling house that looks unrestored and has oddly in its grounds an ornate seaside-looking Edwardian clock tower.

The Windrush tumbles through the weir on this mild winter morning, but the idyll is deceptive as once, at least, the river has seen slaughter. It was in 1388 that Richard II’s favourite, Robert Vere, led his army floundering along this flooded valley, desperate to escape his baronial pursuers, who eventually caught up and cut most of them down a little upstream at Radcot Bridge.

15 February. R. and I go down to Leicester Square at noon, the Tube as crowded as at rush hour, then walk up Charing Cross Road to where the march is streaming across Cambridge Circus. There seems no structure to it, ahead of us some SWP banners but marching, or rather strolling, beside them the Surrey Heath Liberal Democrats. Scattered among the more seasoned marchers are many unlikely figures, two women in front of us in fur hats and bootees looking as if they’re just off to the WI. I’m an unlikely figure, too, of course, as the last march I went on was in 1956 and that was by accident: I was standing in Broad Street in Oxford watching the Suez demonstration go by when a friend pulled me in.

Today it’s bitterly cold, particularly since the march keeps stopping or is stopped by the police, who seem bored that they’ve got so little to do, the mood of the march overwhelmingly friendly and domestic and hardly political at all. I’d have quite liked something to march to, even (however inappropriately) ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’, but the nearest we get is (to the tune of ‘Yellow Submarine’) ‘We all live in a terrorist regime,’ which isn’t a chant I feel entirely able to endorse. At Albemarle Street we split off and go and have lunch at Fenwick’s, having, I suppose, walked a third of the route.

On the TV news the police estimate the numbers at 750,000, the organisers at two million, the true figure presumably somewhere in between. Whether anyone has ever nailed the police on why they routinely overestimate the numbers for demonstrations they approve of (like the so-called Liberty and Livelihood March) while marking down more dissident movements I don’t know. They would presumably deny it as vigorously as their not infrequent throttling of black suspects.

26 February. For much of last year the post in Gloucester Crescent was delivered by a delightful French girl, Stephanie Tunc; blonde and pretty, she was chatty, funny and also very efficient. Unique among the French of my acquaintance she didn’t like France one bit and pulled a face if you told her you were going on holiday there. Before Christmas she and her sister took off for South America and this last week the market men in Inverness Street got a postcard from Stephanie in Peru, which they pinned up on one of the stalls.

Then yesterday the new postman told us that having run out of money in Peru she and her sister had come back from South America to Miami. Sunbathing on the beach they had been run over by a police car, which had then reversed over them. Stephanie was dead and her sister in a critical condition.

‘Add something,’ I note as I transcribe this entry. But there is nothing to add. A lovely, lively girl is senselessly dead. That’s all.

8 March. A phrase often in the mouth of Bush and Blair is ‘Our patience is exhausted.’ It’s a phrase that is seldom used by anyone who had much patience in the first place; Hitler was quite fond of it.

14 March. To Oxford to vote for the chancellor, though it doesn’t seem very long since I did the same for Roy Jenkins. At Bodley I’m overtaken by A.N. Wilson, who’s brought his gown in a Sainsbury’s bag, though it’s part of Roy Jenkins’s legacy that gowns are no longer required on such occasions. This doesn’t stop many of the voters swishing about in them for the benefit of their families, who are then left at the door of the Divinity Schools while the graduate goes in to participate in the mystery. Not much of a mystery now, though, as in another of Jenkins’s reforms there is no ceremony at all and certainly no vice-chancellor enthroned in Convocation waiting to take your voting paper and lift his hat as Patrick Neill tipped his twenty years ago. Now Neill is himself a candidate in what feels more like a local council election, with trestle tables, ushers and the proctors taking the votes. One of Tom Bingham’s proposers, I vote for him and no one else, the single transferable vote (another Jenkins inspiration) likely, it’s thought, to favour Bingham’s chief rival, Chris Patten. At the table I hand in my paper to one of the junior proctors, a weary-looking don who, in what is perhaps a ritual humiliation, demands some evidence of identification. I hand over my Camden bus pass which he scrutinises as grimly as an Albanian border guard, even checking the likeness. Andrew Wilson sails through unchallenged.

I walk back through the streets of Oxford and as always I have a sense of being shut out and that there is something going on here that I’m not a part of; not that I was a part of it even when I was a part of it.

16 March. One of the lowest moments this year was Tony Blair and Jack Straw misrepresenting the French and German position on Iraq in order to encourage xenophobia and get more support from the Murdoch papers.

17 March. A bin Laden associate reported as being ‘quizzed’ by American agents in Pakistan. Were suspects ‘quizzed’ by the Gestapo, I wonder. Other people torture; we quiz.

19 March. What is particularly bitter is to hear one’s own moderate, pragmatic and indeed patriotic sentiments in the mouth of the Foreign Minister of Germany, Joschka Fischer, while our own Prime Minister parrots the American line, a case, I suppose, of Speak for England, Joschka. Meanwhile the troops get ready to ‘rock and roll’, as they call it this time; last time it was ‘shooting fish in a barrel’.

21 March. The first soldiers killed. If our army had been made up of conscripts no one would have tolerated this war for a moment. However much these are ‘our boys’, the war can only be waged because the US and the UK have armies of mercenaries.

24 March. G. was on the bus en route for Camden when a woman opposite leaned across and said: ‘I suppose you think I’ve got this sore throat because I’ve had a cock in my mouth? Actually I’ve been in Germany, but I wasn’t going to let them rearrange my face.’

6 April. All of Rupert Murdoch’s 175 papers are in favour of the war though he always claims that his editors are independent and decide for themselves. I wonder whether the Rupert Murdoch Professorship at Oxford maintains the same fiction. I know I’m a bore on the subject and thought to be an unworldly fool, but so long as it bears his name this grubby appointment is a continuing stain on the reputation of the university that solicited it.

10 April. George Fenton has been in Berlin talking to some of the Berlin Philharmonic with whom he is due to record and conduct his Blue Planet music. They go out to supper in a restaurant in what was East Berlin, a vast converted warehouse where the food is superb. The Germans are all very nice and hugely taken with recent events: ‘The world has turned upside down. The best golfer in the world is black; the best rapper in the world is white; and now there is a war and, guess what, Germany doesn’t want to be in it.’

The sense of impotence is what one never gets used to, of being led into ignominy and not being able to do anything about it except march and, one day, vote.

22 April, Yorkshire. Drive up towards Kirkby Lonsdale then along Wandales Lane, the old Roman road from Burrow to Sedbergh. Walking down one of the green lanes below the fells we come across a fold with a stone stile and in the centre of the fold a boulder so huge it looks like an ancient feature of the landscape, walled for its own protection; an erratic perhaps, carried down and deposited here by the melting glaciers of the Ice Age and then some centre of ancient ritual.

It’s a lovely day and strolling along the lane towards Leck we find a similar fold with another boulder and a hundred yards along a third and a fourth. All are neat, grazed by sheep which have access through a cattle creep under the wall, and all have stiles. They seem ancient, fit snugly into the landscape and are immensely pleasing to look at, some of the pleasure admittedly being in their discovery and their mystery. Are the boulders prehistoric? Or stations along what is plainly an ancient track, some of which is banked up and possibly Roman?

We turn back and drive down to the nursery at Brownthwaite, which is attached to an old-fashioned farm where there are hens and their chickens scuttering about, sheep and today a huge turkey. It’s a farm out of a children’s story, kept by a nice oldish woman and her son, both expert gardeners, their nursery full of rare plants, and ending in a gate to their own garden, which overlooks the valley.

We ask the son about the sheepfolds and he smiles indulgently at the thought that they might be ancient monuments. They’re actually part of an installation or a series of installations by Andy Goldsworthy, who put up a hundred or so similar folds as Cumbria’s Millennium Project. It was an expensive do, costing £500,000 or so, and involved shifting the boulders down from the fells with earthmovers besides building the folds that surround them. An additional burden, I would have thought, was likely to have been the scepticism of the local communities that were home to these ‘sculptures’, though nobody could object that they’re not wholly in the tradition of the countryside in which they’ve been sited. However the only criticism our market gardener has is that Goldsworthy refused to allow any guide to be printed to the location of the folds, the public meant to come across them by accident just as we did and presumably to ask the same kind of questions – who made them, what for and when?

28 April, Yorkshire. Our clock has been losing time, so this morning we pack it up ready to go to Settle to be overhauled. Like a dog being taken to the vet it seems to know where it’s going and as soon as it’s in the box begins to chime, chimes all the way down in the car and only stops when we find that Mr Barraclough, whose retirement job it is, doesn’t have a clock surgery today. So now it’s back home, though still in its box, sulking perhaps, but occasionally giving a plaintive chime.

3 May, Yorkshire. The cherry tree that my father planted just by the back door some thirty years ago is now not much more than a stump. It was radically pruned a few years back in an effort to cure the blackfly that annually infested it, making the leaves clumped and scorched like burned fists. Even then, with so few leaves left, it still got infested, though it was the only tree in the garden that I was ever driven to spray. A few years ago, in desperation, I planted a vine (Vitis coignetiae) just over the wall in A.’s garden (and so in full sun) and began to train it over what was left of the cherry tree. It flourished, so much so that it has covered the stump with its broad heart-shaped leaves, the cherry is virtually obliterated and the tree looks like a mop-headed catalpa. It’s one of my few ventures into creative gardening and the only time I’ve had foresight enough to devise a remedy for a problem and the patience to see it carried through.

One drawback is that with so few leaves there is very little cherry blossom, but this year the coignetiae has compensated for that, too, as its newly emergent leaves are a darkish pink on the front and white at the back so that they look as much like blossom as leaves. It reminds me of a Claude Rogers painting I once tried to buy and now here it is outside the back door.

15 May. After supper we go down to look at the Titian exhibition, now in its last few days at the National Gallery. It’s 10.15 and the doors have only just closed so that the rooms still smell of the hordes that have been passing through; there are screwed up tickets on the floor and abandoned programmes with, a few feet above the clutter, these sublime paintings.

As usual in galleries I feel inadequate and somehow ungiving and am quicker through the rooms than R., like a child wanting to see what’s next, though this means, too, that I can keep having a sit down as I wait for him to catch up. Some of the wonder the paintings inspire is at Titian’s technical accomplishment: his painting of stuff, the fur and the fabric and the raised and knotted embroideries on the fabric, all of which melt into a brown mess on close examination, and only achieve form when one steps back. Oddly favourite is a portrait of the (unappealing) Pope Paul III in a faded rose-coloured cape enthroned on a worn velvet chair, the supreme pontiff just a lay figure there to demonstrate the painter’s skill with his materials. Next to him the irresistible portrait of the 12-year-old Ranuccio Farnese and another of Clarissa Strozzi that could almost be by Goya.

Least impressive is the much advertised reconstruction of Alfonso d’Este’s camerino which doesn’t work because a. the room is too large b. certain elements are missing and c. the NG’s Bacchus and Ariadne apart, I don’t altogether like the paintings. I don’t care for his last pictures much either, while recognising how (in every sense) far-sighted they are. The Flaying of Marsyas is a disturbing picture, the detachment of the satyrs watching the torture of their fellow creature chilling; Marsyas’ upended eye, blank with a horror beyond feeling or fixed in death, is done with a single dot of white paint, a dot I’d like to see enlarged or in detail.

Now it’s a quarter of an hour before midnight and we walk back through the dark and deserted gallery, the feeling of privilege we had when we were first able to do this ten years ago never lost; it’s the greatest and most tangible honour I have ever been given.

Lying in bed, though, I think of the time I invited Alec Guinness to go round with me. Having given him careful instructions which door to come to I waited in the lobby until well past the appointed time. Never late he eventually arrived cross and out of sorts, claiming I had sent him to the wrong door. I hadn’t, but I should have known that any attempt to return his always munificent hospitality would end in tears. He so disliked being beholden to anyone that he was bound to fuck things up if you tried to give him a treat. Though whether he knew this (or knew it about himself) was never plain.

26 May, Yorkshire. A dullish day, though fine enough to garden, which we do until, around five, we take some rubbish down to the dump in Settle. It used to be on the edge of a disused quarry and reminded me of the place where the Virgin Mary appeared to St Bernadette at Lourdes, as seen in The Song of Bernadette, a film which terrified me as a child. Now it’s in Settle itself, an immaculately kept installation below the railway with a series of skips all lined up and with steps and a platform as for the launching of a ship rather than the filling of a skip. The man in charge has a commodious hut, where he may very well live, and is cheerful and helpful and this, plus the fact that disencumbering oneself of rubbish always lifts the heart, makes most people come away in a cheerful frame of mind. It isn’t all rubbish, though, and today as I junk some of the mysterious accoutrements that always come with a vacuum cleaner I spot some quite ancient-looking decorated wood. Alas, one of the rules of the establishment (displayed on a painted board) is that one cannot go through the contents of the skip, so I have to leave my fancied medieval panels to their fate.

Afterwards we go the back way along the Feizor road, stopping to walk up the green lane towards the Celtic wall. The lane is lined with patches of water avens, the dusky purples and pinks in its strawberryish flower growing in among the spikes of yellow wood spurge, an arrangement more effective than anything you’d get at Pulbrook and Gould.

29 May. That Tony Blair (as today talking to troops in Basra) will often say ‘I honestly believe’ rather than just ‘I believe’ says all that needs to be said. ‘To be honest’ another of his frank-seeming phrases.

11 June. Why isn’t more fuss made over Charles Causley? Looking through his Collected Poems to copy out his ‘Ten Types of Hospital Visitor’ I dip into some of his other poems, so many of them vivid and memorable. Well into his eighties, he must be one of the most distinguished poets writing today (if he still is). But why does nobody say so and celebrate him while he’s still around? Hurrah for Charles Causley is what I say. [Too late. He dies 4 November.]

23 June. The woollen hats worn by boys nowadays often take the form of medieval basinets or such helmets as soldiers wear in a French Book of Hours. A boy comes by this morning with just such a helmet looking as if he might be coming off duty from the foot of the Cross.

25 July. John Schlesinger dies. The obituaries are more measured than he would have liked, the many undistinguished films he made later in life set against A Kind of Loving and Sunday, Bloody Sunday. He wasn’t by nature a journeyman film-maker taking whatever came along, but was forced into this way of working by having three houses to keep up, one of them in Hollywood, and always leading quite an expensive life. What none of the obituaries says is how much fun he was to work with, though no one had a shorter fuse, besides being wonderfully funny, particularly about his sex life.

Short, solid and fat, John looked like the screen Nazi he had once or twice played in his early days as an actor; he was a scaled down Francis L. Sullivan, managing nevertheless to be surprisingly successful in finding partners. Not invariably, though. Sometime in the 1970s he was in a New York bath house where the practice was for someone wanting a partner to leave the cubicle door open. This Schlesinger accordingly did and lay monumentally on the table under his towel waiting for someone to pass by. A youth duly did and indeed ventured in, but seeing this mound of flesh laid out on the slab recoiled, saying: ‘Oh, please. I couldn’t. You’ve got to be kidding.’ Schlesinger closed his eyes, and said primly: ‘A simple "No” will suffice.’

6 August. Driving along the back road from Muker to Kirkby Stephen we spot down in the valley another of Andy Goldsworthy’s circular sheepfolds and a mile or two further on a complex of folds that at first we take to be a development of his art but which on closer examination turns out to be the real thing: a series of three or four walled enclosures set round a one-chamber single-storey cottage used for dipping and shearing sheep. And still used, seemingly, the long stone-lined pit brimming with evil-looking oily dip, a ragged fleece hanging by the wall and the ground carpeted in flocks and curds of wool. It’s a sinister place and much as it must always have been, an old board blocking one of the cattle creeps hinged with scraps of ancient leather. That it can at first sight be mistaken for one of Goldsworthy’s installations says much for the authenticity of his work.

14 August. Another death: Cedric Price, for many years the partner of Eleanor Bron and an inspirational figure to many architects. He was a figure of 18th-century exuberance with views on conservation that were shockingly at variance with received wisdom. Cedric didn’t believe in preserving buildings that had outlived their usefulness; he would have made a good character in a modern-day Ibsen play. At Cambridge as an undergraduate he was once in the Rex cinema when the adverts came on, including one for Kellogg’s Ricicles. ‘Rice is nice,’ went the jingle, ‘but ricicles are twicicles as nicicles.’ Whereupon Cedric boomed out: ‘But testicles is besticles.’

By their jokes ye shall know them.

The elegance of the black building crew up the street is a constant delight. Today one comes down the street in a lemon-coloured shirt, his head wrapped in a bandana of matching shade and a white dust mask pushed up above his forehead. He is like a wonderfully exotic rhinoceros, but with a grace and self-assurance that wouldn’t be out of place on the catwalk.

24 August. Our GNER train from Leeds stops at Retford, where passengers are bussed down the A1 to Grantham, the line between being under repair. It’s around seven and the clouds are beginning to break up and the journey is redeemed by a vision on the eastern horizon of the towers of Lincoln Cathedral, caught in the late light of the setting sun. It’s the kind of thing that would have immensely excited me as a boy (and quite excites me now). I’ve driven up and down this road hundreds of times and never seen it before, but that’s because in a coach you’re hoisted above the hedge and given an artist’s prospect of the countryside.

28 August. T. Blair claims to the Hutton Inquiry that if the BBC had been right and the Iraq dossier had been ‘sexed up’ he would have resigned. This is presumably intended to pre-empt any calls for his resignation at the conclusion of the Inquiry, which, whether it reports so or not, has conclusively shown that this is exactly what happened to the Iraq dossier. I suppose ‘sexed up’ is a euphemism for ‘hardened up’ (‘stiffened up’ even), fastidiousness about language not being one of the characteristics of Blair and Co; one of the many distasteful aspects of the whole affair is that anyone (Lord Hutton included) engaging with the issues has to do so in the language dictated by Number 10.

15 September. At Thora Hird’s memorial service in Westminster Abbey the best joke is Thora’s own. When she was beginning to fail but was still living on her own in her mews flat she would sometimes get confused and ring her daughter Jan for reassurance. She rang one day to say: ‘I’m in the studio doing this picture with John Wayne. Only he’s gone out and left me. And everybody else has gone out and left me and I’m stuck here on my own.’

Jan said: ‘Mum. You’re not in the studio. You’re in the flat in the mews.’

Thora said: ‘I am not. I’m in the studio with John Wayne and the beggar’s gone out and left me.’

Jan said: ‘Mum. You’re in the flat. Look out of the window. Is that the mews?’

Pause. ‘Well, it looks like the mews . . . but they can do wonders with scenery nowadays.’

25 September. To Folkestone to speak at the Saga-sponsored literary festival. We have tea at a seafront hotel and sitting on the balcony in the warm sunshine I reflect on how seldom it is that I see the sea. The tide is in and the waves are breaking only a yard or two from the road and although it’s quite busy there is something restorative about sitting here, watching the brown waves edge up the narrow beach. On the horizon to the south is the power station at Dungeness and beyond it, I imagine, Derek Jarman’s now much visited cottage, trips to it one of the features of the festival. There are three or four ships motionless on the horizon, putting one in mind of Larkin’s ‘To the Sea’, though there is no ‘miniature gaiety of seasides’ here, just the occasional grim jogger toiling along the front.

Saga itself turns out to be a tall modern block set in a steep park above the sea and alongside the offices an even more modern auditorium up to which several senior citizens are already labouring. The lavishness of the set-up – the vast terrace outside the auditorium above the sea, the spacious park and the many-storeyed office block – combine to make it slightly sinister, as if the ostensible purpose of the organisation, the interests and welfare of old(er) people, is just a front as it would be in a Bond film, say, a cover for international criminality with a hatch opening in the cliffside parkland to reveal a hangar humming with the mechanism of some project that will take over the world. And all the thousands of employees are old. As the audience certainly are at my meeting, though very amiable and jolly. At the finish I am presented with a stick of Folkestone rock the size of a barber’s pole, sign books for an hour and then get the train back; home by 10.30.

30 September. A memorial service for John Schlesinger. It’s in the synagogue opposite Lords and though it’s Liberal Jewish I don’t feel it’s quite liberal enough for me to tell the bath house story. Still, there are a lot of laughs in the other speeches, so I do feel able to give John’s own account of his investiture with the CBE. John was so aware of his sexuality that he managed to detect a corresponding awareness in the unlikeliest of places. On this occasion HMQ had a momentary difficulty getting the ribbon round his sizeable neck, whereupon she said, ‘Now Mr Schlesinger, we must try and get this straight,’ the emphasis according to John very much hers and which he chose to take as both a coded acknowledgment of his situation and a seal of royal approval.

4 October. To Ely to look at the cathedral, last visited all of twenty-five years ago when the town was still a lost place like Beverley or Cartmel. Nowadays, like so much of East Anglia, it thrives and today is the Harvest Festival, at the west end of the nave a pen of sheep and a few roosters crowing their heads off and in odd corners all over the cathedral little heaps of baked beans, cling peaches and custard powder, the staples of such occasions, and which, as Clive James noted, will later be distributed among the poor and devout old ladies who contributed them in the first place. A truer symbol of the locality’s harvest would, I suppose, be a sheaf of emails or a roll of print-outs, electronics round here more profitable than agriculture. The sheep attracting most of the visitors, the rest of the cathedral is blessedly quiet and there is much to see. Our favourites are a little eccentric, with mine the late 15th-century cloister arcades outside the south door, bricked up presumably at the Dissolution, and R.’s a fragment of wooden tracery from the prior’s study and the framework of a door that once housed the library cupboard for the monks. But there’s much more spectacular stuff, even though the methodical iconoclasm of East Anglian puritanism is more in evidence here than at York, say, with even the little fragment of glass preserved and restored in one of the cloister windows having the Virgin’s face scratched out. Every statue and saint is headless or faceless, with the mutilations in the Lady Chapel looking so fresh they might have been done by the vandals of today.

The shop is doing a brisk trade in tea towels, table-mats and all the merchandise that were I Jesus I’d be in there overturning. And, as always, no decent postcards, the want of a proper series of black and white reproductions of architectural details such as you find in French cathedrals an indictment of . . . whom? The cathedral chapter? The dean? Unenterprising photographers? Or just, as Lindsay Anderson would say, ‘England!’

Why the west tower is not one of the wonders of European architecture I don’t understand. It’s as extraordinary and as asymmetrical as Gaudí and a staggering achievement for its time, every bit as astonishing as Pisa, which its arcades recall, though lacking the lean that would put it in the big league, and have people gawping (which of course I wouldn’t want anyway). ‘Oh, grumble, grumble,’ says R.

15 October. The Earl of Pembroke, Henry Herbert, has died. I met him only once in July 1974 when I had to do a Kilvert recital in the Double Cube room at Wilton. He was charming and easy but it didn’t go well for all sorts of reasons, some sad, some comic. The evening was to have been introduced by Cecil Beaton, but earlier that week he had had a stroke and this overshadowed the proceedings. Princess Alexandra was the guest of honour but being Kilvert there was quite a bit about little girls’ bottoms and such-like so this put rather a damper on things as royalty often does, or did in those days anyway. I was wearing a new velvet suit and it was only afterwards I found that my flies had been open throughout. ‘Never mind,’ said the lighting assistant. ‘The spot was on your face.’

The story wouldn’t be worth telling except that nearly twenty years later when The Madness of George III was playing at the National Henry Herbert wrote to me about the Lady Pembroke who figures in the play. This was a lady of mature years to whom in his derangement George III takes a fancy; she was a woman of some dignity who did not in the least reciprocate his attentions, which were something of a joke at Court. Herbert’s letter filled in the family tradition about this ancestor with an anecdote told him by his father:

Lady Pembroke’s husband, Henry, was charming but he was also a shit and the King was so incensed by the Earl’s behaviour towards his wife that he demanded to know what possible excuse he had for treating her so badly. To which the Earl replied: ‘Sire, if you had a wife whose cunt was as cold as a greyhound’s nostril, you would have done the same.’

Twenty years after the Kilvert recital we went back to Wilton to film part of The Madness of King George, by which time Richenda Carey who had played Lady Pembroke on the stage had had to give way to the less matronly Amanda Donohoe, star of Castaway and more what Hollywood thought audiences were entitled to expect in a fancy woman, and one unlikely to be suffering from her historical counterpart’s genital hypothermia.

19 October. Watch the second part of ITV’s Henry VIII with Ray Winstone as the much married monarch. It’s no better than the first half and as wilfully inaccurate, the Dissolution of the Monasteries presented as if it were some Viking raid, with troops riding down the fleeing monks, hacking them to death as they try to rescue the monastic treasures. It’s a far cry from the peaceful retirement on a small pension that was the lot of most of the monks and nuns, with the actual dismantling of the fabric and the selling off of the furnishings far more interesting (and far more interesting to watch) than these silly melodramatics.

Aske, the leader of the Pilgrimage of Grace (played by Sean Bean), is pictured being hauled up outside Clifford’s Tower in York, with the wicked Duke of Norfolk ordering that he be left to hang for three days, presumably to die of exposure. This is picturesque nonsense. Aske was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered and though there’s seldom much to be said for Henry VIII in the clemency department he did at least agree to Aske’s request that he be hanged and allowed to die before the rest of the sentence was carried out.

In the same programme Thomas Cromwell is pictured as being inexpertly despatched by a novice executioner, Cromwell’s face contorted in agony as the first two blows fall, his head only cut off by the third. This, too, is fanciful. Certainly there must have been many botched beheadings, but Cromwell’s was not one of them, the executioner (whose name is known) taking off his head at a stroke.

In a programme as poor as this it might seem pedantic to be concerned about such details. But there is more than enough savagery in the reign of Henry VIII without adding to it.

4 November. Passing through Cambridge we pay a ritual visit to Kettle’s Yard. It’s a house that never fails to delight and though there are features I don’t like (too many artful arrangements of pebbles, for instance), it’s a place I could happily live in. The attendants are mostly elderly and many of them seem to have known Jim Ede, whose house it was and who gave it and its art collection to the university in the 1970s. One particularly sparky old lady recommends a video display running in the big room downstairs. At first it simply seems to be a slightly blurred record of a domestic interior: a kitchen, a sitting-room with on the floor some toys including a couple of model planes. Suddenly one of these planes takes off, then another lands and soon the kitchen and dining-room have turned into a busy international airport, planes crossing the room, landing on tables, taking off from work surfaces and all in total silence. They negotiate the narrow chasm of a slightly open door, deftly avoid a light-fitting or a bowl of fruit and it’s so absurd and silly I find myself grinning like a child. The artist, whose name I forgot to write down, is Japanese and it’s the last thing I’d ever have chosen to watch or expected to find in the austere surroundings of a house like this, but it’s a delight.

15 November. Around nine I go out to put some rubbish in the bin to find someone curled up on the doorstep. I say someone because swathed in an anorak it’s impossible to tell whether it’s a man or a woman; he/she doesn’t speak and when shaken just moans a little. He/she is surrounded by half a dozen plastic bags, most of them empty and not the carefully transported possessions of the usual bag lady, if it is a lady. So, having talked about it, we eventually ring 999 where the Scotland Yard operator is quite helpful and within ten minutes (on a Saturday night) a squad car comes round with two policemen. They’re sensible and firm with what turns out to be a young man. He’s filthy, his hands so black he might have been shifting coal, and is no help when they try to get him on his feet, moaning still and saying he has an abscess. Now an ambulance arrives, and it’s this that seems to bring the young man round. He plainly doesn’t want to go to hospital, and abandoning whatever possessions he has on our doorstep, vanishes into the night. One of the policemen comes back and explains that, because among the rubbish is a squeezed-out lemon, he is likely to be an addict, the juice used to purify the drugs. He counsels caution when we’re clearing up the mess lest there be any needles about and then says, ‘Actually I can do it,’ goes to the car for some gloves and tidies everything away himself and in such a sensible, straightforward way it seems genuine goodness. It makes me ashamed of my habitual prejudice against the police when here is one dealing with what for him is presumably a regular occurrence and going out of his way just to be helpful. I think what a dispiriting job it must be night after night coping with the thieves and addicts of Camden Town and how hard it must be not to despise respectable folk who call them in to solve what for us is just a problem of hygiene. With a final instruction to swill down the flags he goes off in the squad car, I go up and have my bath and then we sit down to our shepherd’s pie. Among the contents of the bags that constitute the young man’s possessions were part of a safety belt, presumably used as a tourniquet, a candlestick with a stub of a candle, a packet of Yorkshire puddings and, unaccountably, some rosemary.

21 November. I see from the paper this morning that while I was trudging up Whitehall past the end of Downing Street on the second anti-war march Tom Stoppard was in Downing Street having lunch with Mrs Bush. While she was there apparently they watched some children doing Shakespeare. I would have felt uncomfortable about this for various reasons, not least because it comes so close to a playbill done the night before at the Royal Court. This included an extract from Tony Kushner’s next play in which Mrs Bush visits a school and talks to the children about literature and (slightly improbably) Dostoevsky. As she chats to them she slowly realises that all the children are dead. In the same programme there’s another playlet, Advice to Iraqi Women by Martin Crimp. I’d dearly love to have written both of them and it would have done more good, I’m sure, than going on the march.

15 December. As I’m correcting the proofs of this Diary the news breaks of the arrest of Saddam Hussein. It ought to matter, and maybe does in Iraq; it certainly matters in America. But here? Whatever is said it does not affect the issue. We should not have gone to war.

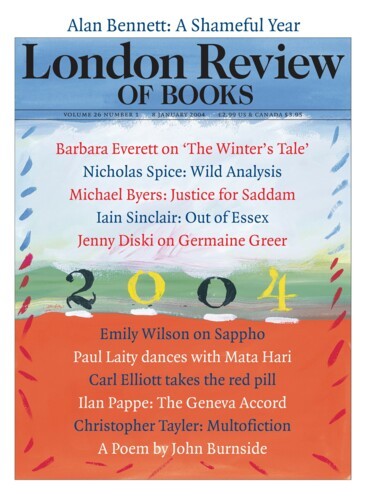

It has been a shameful year.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.