Turner’s remark ‘Had Tom Girtin lived, I should have starved’ is as good a posthumous puff as any artist ever gave another. It’s printed on the back of Tate Britain’s Girtin catalogue. There it reads as a challenge. It puts you on your mettle as you walk past the many pictures whose original effect must be reconstructed from sheets that time has rendered curiously rusty or unnaturally blue.

Transparent watercolour – the medium Girtin used and developed – allows passing effects of light and weather to be set down swiftly. An oil sketch (one of Corot’s made in the South of France, for example) can record heat, strong shadow and bright light. Watercolour, used strictly as a medium for painting (coloured drawings such as Rowlandson’s, in which pen-line holds the form, are a different matter), comes into its own at dusk or at dawn, when clouds gather and rain begins to fall, or when mist diffuses light. With it, subtle effects can be recorded – such as the juxtaposition of pale shades in sky and clouds. Layers of transparent wash can give depth to murky shadows. But the force of other kinds of work on paper is hardly diminished by the degrees of fading or darkening which leave pictures like Girtin’s slumped on the ropes. A careless choice of materials or putting a picture on a wall rather than keeping it in a portfolio can have a disproportionate effect. In the exhibition, problems of condition are explained and displayed: a strip of a painting formerly protected by a mount shows unaltered blue greys, which exposure to light has turned to brown over most of the picture area. The comparatively small number of pictures that can be reckoned to look much as they did when they were new can be used to measure change in others. Among the guilty fugitives, whose departure has made monotone what was polychrome, are indigo (blue), gamboge (yellow) and brown lake (purple).

Thomas Girtin was born in 1775 and died at 27, perhaps of asthma, although nameless dissipation and even sitting sketching on cold ground have been given as possible causes of death. What he achieved in his short life shows how various the tasks undertaken by a professional watercolour painter could be – and how hand-to-mouth his existence. Girtin’s first commissions were copies after prints and worked-up versions of amateur drawings of scenery and antiquities. Later, he would spend the spring, summer and early autumn touring in search of scenery, and would take back what he drew and painted on the spot to use as the basis for studio work done (along with teaching) in the winter. He exhibited at the Royal Academy and had a number of loyal patrons. Among his pupils were women of means and influence. The major work of the last part of his life was a panorama of London – painted in oil and covering nearly two thousand square feet. There were prints (mostly published by Girtin himself) made from his work. His wonderful study of a strangely empty rue St Denis is without the usual crowd of figures because it was to be translated into stage scenery. All of these kinds of work are represented (although for the panorama only studies survive) in the exhibition. It is topped with work by earlier painters – Edward Dayes, to whom he was apprenticed, Michael ‘Angelo’ Rooker and Paul Sandby among them – and tailed with pictures by those who were influenced by him: including Turner, de Wint, Cotman and Constable.

For a sense of why Girtin matters it is best to start with his late watercolours, the views of Guisborough Priory, Kirkstall Abbey and Storiths Heights, all painted with a breadth that some contemporary critics thought slovenly, but which fits well with modern taste – Cotman, after all, is now the best loved and most praised English watercolour painter.

The White House at Chelsea (1800), with its distant view of a strip of riverbank, a windmill, a couple of church towers, boats and a pale evening sky, is an evocation of landscape that suggests a scientific precision of observation. Yet it was only by selection, editing and rearrangement that the facts of nature were marshalled. Affecting images like this one signalled a new sensibility.

In the late 18th century, tourists who, a generation before, would have been better attuned to the park-like scenery of Claude and Poussin, learned to appreciate different, often more austere landscapes. It was a change encouraged by, and evident in, pictures by the watercolourists who were carrying forward the banner of the British sublime. Things which, to the uninitiated, seemed damnably uncomfortable and visually bleak became a source of pleasure. When a tour bus stops today for a photo opportunity, it is often at a scene made famous two hundred years ago in English topographic art. Country Life recently asked its readers to nominate the best views in Britain. The top two, selected from the most popular nominees by a panel including Jeremy Paxman and Joanna Trollope, were Salisbury Cathedral from the water meadows – Constable taught us that one – and Buttermere, which we learned from Turner.

Photographers have also put their mark on nature, using devices learned from, or at least familiar in, landscape painting. The Ansel Adams photographs on show at the Hayward (until 22 September) make art out of views of the Californian wilderness. The scenes are framed, and the scale of greys in the prints adjusted, in ways that would have been perfectly comprehensible to the 18th-century tourist who admired just such bright clouds and sombre masses in his Claude glass or in a painted view. Adams did commercial work as well as the pictures of wild nature he is famous for: natural history illustrations, views of foreign places, even the equivalent of holiday snaps – photographers, rather than artists, were now the ones sought after for odd-job commissions. In the sketches Girtin made for his panorama of London such journeyman skills are more important than a romantic feeling for dramatic scenery. These sketches are records of what can be seen, not images to trigger feelings. Hydrographers made drawings of coastlines which are not unlike them. There is a premonition here of a taste for the ordinary. You have to look a long way forward – to something like Boudin’s harbour scenes – to find it in gallery art.

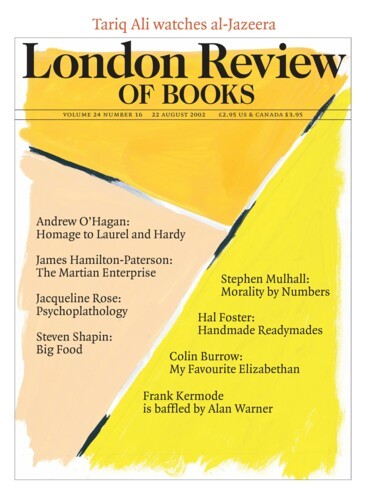

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.