Ephemerality shows its sweet sad face when the yellowing edges of books you remember buying, and of letters you remember receiving, remind you that it all happened a long time ago. The ability old paper has to set events in time past is not just a personal thing. In Century City: Art and Culture in the Modern Metropolis (until 29 April), Russian film posters, Japanese avant-garde magazines, cheaply produced books from Nigeria, satirical weeklies from 1900s Paris – things piled on stalls and pasted on walls, cheaply made and quickly discarded – tell of their time more reliably and engagingly than great art (of which Century City is not short).

The exhibition is very large, sporadically wonderful, frequently banal, and sometimes over-directed, in the sense that the art often refuses to bear witness to the curators’ view of things, or is reduced to the status of illustration by being too firmly captioned by its context: see the Kokoshka and Schiele paintings and drawings decorating the walls of the chapel in which Freud’s couch is the altar.

Print – printed ephemera in particular – demands a quick response. The publicist amuses the party while the artist works away in the back room. You can go along with that view of the relationship when you turn from the row of early Cubist paintings by Picasso and Braque to the case showing contemporary copies of Le Rire, L’Assiette au Beurre or Le Frou-Frou. But before you make this comparison you have probably already passed through the Moscow rooms and are aware that quite different deals could be struck.

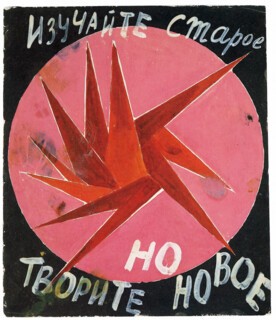

There, briefly, in the 1920s the boys from the back room took over the whole show. Before the academic easel painters had time to regroup as Social Realists and Stalin pulled the plug on Modernism, an argumentative cohort of Constructivists and Supremacists had a chance to try their utterly confident, highly theorised, future-directed way of image-making and image-editing on the stage, in film, in posters, books and magazines. The rooms which show this, splendidly, are the best in the exhibition. The results in print graphics were wonderful. Sharp geometry, type at odd angles, circles for stability, triangles for dynamism, bits of photographs for probity. It was something which could never have taken place in the commercial environment of the Paris news-stands. When Stalinism had done its worst Rodchenko, El Lissitzky and Stepanova could still work in design and photography on the magazine USSR in Construction, which celebrated Soviet progress. A style made for a new socialist world was adapted to the job of advertising the achievements of centralised power.

In Japan in the 1960s print took on a quite different Modernist function. It brought a note of refinement and prettiness to protest. Between 1969 and 1972 Horikawa, as an awareness-raising exercise, sent stones – large pebbles really – to various addresses. It was around the time of the Moon landing. One went to President Nixon as a Christmas present. Horikawa wrote: ‘Nothing changes in the universe if humanity stood on the Moon and brought back the stones. What does change is humanity and his thinking.’ Whatever that may mean exactly, you would not gather from it how nicely tied and labelled the stones were. The stamps, franking and address are like a footnote in a page of Saul Steinberg’s The Passport, the whole item as elegant as one of the examples of traditional Japanese packaging in How to Wrap Five More Eggs. Akasegawa’s Greater Japan Zero-Yen Note failed as a quixotic attempt to put the state’s currency out of circulation. As represented here with printed valueless currency and two glass jars full of mailers from (I presume) those who sent three real 100-yen notes in return for one authentic zero-yen note, it has some of the mystery of a Joseph Cornell box. Yokoo’s posters for the Situation Theatre are masterpieces of delicate, allusive kitsch. In every case a Japanese talent for elegant presentation contrasts with conceptual ambitions which, in Europe and America, have drawn on cruder archetypes.

The Russian avant-garde tried to take over the show when revolution destroyed the marketplace, the Japanese turned a national talent for the exquisite to subversive ends. When you bring things up to date and come to London and Bombay in the last decade of last century the categories of high art and low, of commercial and non-commercial are meaningless. The ironic borrowings of pop art are replaced by an overlap in which posters for commercial films in Bombay and fashion magazine photographs in London are categorised not by what they are but by the frame of reference they are placed in – art in the gallery, publicity in the street. This elision, which takes place almost unnoticeably in the medium of print, is evidence that the membrane which seemed to separate art from non-art is now entirely permeable.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.