In February 1932, on the occasion of George Moore’s 80th birthday, a group of distinguished London literati published an encomium in the Times paying homage to ‘a master of English letters’. Today there are few critics who would find a place for him in a pantheon of English novelists – of his 16 novels and numerous short stories, only Esther Waters counts as a ‘Penguin Classic’. That said, Moore’s social life and literary career continue to provide a fertile ground for enthusiasts; more often than not as source material for whimsical and mildly defamatory character sketches. Adrian Frazier’s painstakingly researched new biography of Moore marks a considerable advance on Joseph Hone’s respectful but pedestrian 1936 standard biography and Tony Gray’s lively but unscholarly 1996 Life.

Moore was born in 1852 into the West of Ireland ‘hard-riding country gentry’ idolised by Yeats. His childhood playgrounds were the sombre, boggy landscape and the racing stables of Moore Hall on the shores of Lough Carra in County Mayo. He was sent to Oscott, a Roman Catholic boarding school near Birmingham, where his academic career was undistinguished: in December 1865 the headmaster Spencer Northcote wrote to Moore’s father to inform him that concerning Master George’s ‘progress in learning I can scarcely say too little’. His father, George Henry Moore, a successful racehorse owner and politician, was convinced his eldest son was a dunce and took the time-honoured step of attempting to browbeat him into an Army career. Moore junior balked at the discipline of military training college and was mercifully, if guiltily, liberated from Army life by his father’s death in 1870. ‘I sprang like a loosened bough up to light’ was Moore’s comment. Inheriting a not inconsiderable fortune, the misunderstood and unappreciated Moore set off for Paris in March 1873 hoping to become an artist. As he later put it, ‘I longed for fame, brutal and glaring.’

Once in Paris, Moore assumed a pose as le plus Parisien de tous les Anglais. After abortive attempts to become a painter and poet, he settled into his true vocation as a flâneur manqué. He had his head turned by the Impressionist painters who frequented the Café Nouvelle Athènes on the Place Pigalle. Manet, Degas, Renoir, Pissarro and Monet were among those with whom he could idle away the day in endless conversation in his patchy and unidiomatic French, often a source of hilarity to his Parisian acquaintances. Moore would claim in his Confessions of a Young Man (1888) that the Nouvelle Athènes had been his substitute for Oxford and Cambridge, and he may have picked up his education in Parisian cafés and salons, ballrooms and bar-rooms, but there was an accompanying loss. He had an aversion to systematic education, claiming that scholarship left the essential mysteries of art untouched, but his refusal or inability to sweat for knowledge exacerbated the limitations of a truculent critic who remained all his life, as Desmond MacCarthy put it, ‘a dipper’. That said, Confessions of a Young Man, written with a young man’s boastfulness and high spirits, did much to create the legend of the decadent and bohemian Montmartre of the 1870s and 1880s in the minds of English readers.

Moore’s stay in Paris was cut short by the agitation of the Land League in Ireland and his Mayo tenants’ refusal to pay their rents. The sudden loss of income led him to move to London, lodging in dignified frugality in the Strand while he embarked on a career as a journalist and novelist. His response to his change of fortune in Confessions was characteristically extravagant: ‘That some wretched farmers and miners should refuse to starve, that I may not be deprived of my demi-tasse at Tortoni’s, that I may not be forced to leave this beautiful retreat, my cat and my python – monstrous.’ The swagger of the aristocratic dandy (not to mention the fabrication of non-existent miners) sits oddly beside the sentiments of the author of Esther Waters (1894) – the tender story of an uneducated maidservant’s struggle to bring up her illegitimate child.

In one scene, Esther, employed as a wet-nurse by a Mayfair society lady, is refused permission to nurse her own sick child for fear that her employer’s baby will wake and cry for milk. Esther defends her baby’s right to exist and tells the frantic Mrs Rivers to nurse her own child. And then the Rivers baby begins to cry. I’d be interested to know whether it was Moore’s implication that class divisions can outweigh the shared bonds of motherhood that led Virginia Woolf to describe Esther Waters as ‘this novel without a heroine’, as if she doubted that servants were a proper subject for serious literary representation. Moore was certainly one of the first to bring the approach and methods of French naturalism to English fiction. He made a pilgrimage to Médan to meet Zola and like his master, he courted controversy, offending the guardians of the circulating libraries of Mudie and W.H. Smith with his assault on the hypocrisy, respectability and complacency of the late Victorian reading public.

In another powerful set piece, Esther reproaches William, the father of her child, with the consequences of his desertion while their crying son stands close by, clutching the toy boat his father has given him and off which Esther has snapped the masts in a jealous fury. By contrast with the sentimentality that envelops many Dickensian heroines, there is an integrity of tone in Moore’s portrayal of his stubborn, quick-tempered domestic servant. Similarly, Esther Waters does not compare unfavourably with Hardy’s Tess. Esther and William’s reconciliation during a colourful outing to Epsom Downs on Derby Day, and the ending, which shows Esther settled in the Sussex countryside after William’s death, make Hardy’s novel feel excessively grim. Dickens and Hardy far outdistance Moore in imaginative vigour and invention, of course, but his naturalistic novels afford satisfactions that have been unduly neglected. In fact, Moore thought of Esther Waters as more Flaubertian than Zolaesque and perhaps the most instructive approach to his novels is that which argues that Moore found a middle way between realism and aestheticism, influencing Joyce and therefore the course of the 20th-century novel.

The most amusing and informative sections of Frazier’s biography are those which outline Moore’s flirtation with the Irish Literary Renaissance. Increasingly dissatisfied with the naturalistic novel and appalled by English imperialism at the time of the Boer War, Moore decided to leave London for Dublin. He collaborated with Yeats on Diarmuid and Grania, a three-act prose play based on Celtic mythology, but differences of taste and temperament put an increasing strain on their friendship, which reached breaking point when Moore accused Yeats of plagiarism. Moore’s suavely gossipy, almost libellous autobiographical trilogy, Hail and Farewell (1911-14), contained a mischievous portrait of Yeats, who responded in Dramatis Personae, a series of vignettes designed to deflate Moore’s reputation and standing in the Irish literary movement. Yeats tells a number of anecdotes on the subject of Moore’s escalating squabbles with his Dublin cooks and neighbours, culminating in the story of a trap set to capture a neighbour’s cat which threatened a blackbird that sang in Moore’s garden, but which instead snared the bird. Moore’s talent could not flourish in Ireland. His inveterate dislike of his native country didn’t endear him to the Irish Literary Theatre, let alone to the strongly nationalist Gaelic League; the IRA set fire to Moore Hall in 1923.

Moore’s final literary persona was as ‘the sage of Ebury Street’, his home for the last two decades of his life. It was here that he composed his ambitious historical romances, The Brook Kerith (1916), which is concerned with St Paul’s discomfiture on discovering that Jesus had not, after all, died on the cross and ascended to heaven but was tending sheep in the Jordan Valley, and Héloïse and Abelard (1921), an attempt to re-create the world of medieval romance. He did his literary fieldwork in Palestine and travelled to Tours as if in an attempt to breathe the air of 12th-century France. But both works record his disenchantment with naturalism. Seduced by Pater’s delicate cadences and Yeats’s measured prose, Moore had come to believe that his earlier stylistic restraint had amounted only to a studied artlessness. The carefully crafted narratives of The Brook Kerith and Héloïse and Abelard are not wholly successful: the rambling paragraphs are laboured and overwritten, ‘ribbons of toothpaste squeezed out of a tube’ according to Yeats.

If Moore’s historical romances ceased to interest young, experimental novelists, he still had some influence as a garrulous elder statesman of letters. Conversations in Ebury Street (1924) records some of the literary chit-chat that apparently took place in the drawing-room of No. 121, although the conversations sound artificial and savour too much of an after-dinner raconteur enjoying the sound of his own voice. ‘Never did anyone talk such nonsense as George,’ Virginia Woolf wrote to Vita Sackville-West in 1926. A large part of the problem was Moore’s summary dismissal of contemporaries such as Hardy, James and Conrad. Jealous of his literary fame, Moore was aptly described by Joseph Hone as ‘the least catholic of critics’.

It is easy to underestimate how unpleasant it could be to meet so eccentric and belligerent a figure as Mr Moore. His compulsion to shock was nowhere more evident than in his relations with women, although his proclivity to boast of amorous conquests or to trail an indiscretion under the nose of the reader is more likely to irritate than intrigue. ‘I love women as I love champagne,’ he wrote in Confessions. ‘I drink it and enjoy it, but an exact account of every bottle drunk would prove a flat narrative.’ Few of those who knew him were inclined to believe his stories, and many, including Yeats and Woolf, doubted he was capable of much more than risqué correspondence, voyeurism and bottom-pinching. The Dublin wit Susan Mitchell remarked that with Moore it wasn’t so much a case of kiss and tell as tell and not kiss. His self-dramatisations might be traceable to his parents’ taunts that only an old and ugly woman would wish to marry him. Unrequited love led him unchivalrously to boot Pearl Craigie’s backside during a walk in Hyde Park – or at least to fantasise about doing so. Telling stories was his refuge from an indifferent mother, an overbearing father and a lack of belief in his personal appeal; in particular, literary portraiture was a way for this lonely bachelor to make himself attractive. For a man who swore that he would die childless, it would be fascinating to know whether, as Frazier speculates, Nancy Cunard really was his daughter, the offspring of an affair with Lady Maud Cunard.

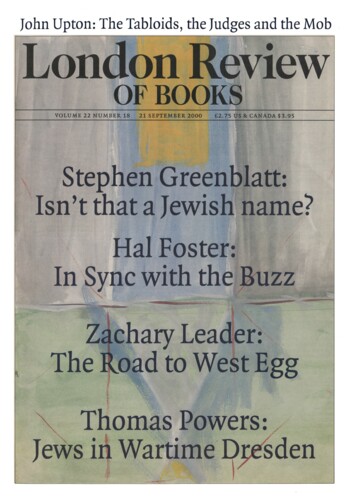

The cover of Frazier’s biography shows Manet’s portrait of Moore: the long, pallid face, dreamy blue eyes and wispy, blond beard with a wild hint of red, bring to mind Yeats’s description of Moore as a ‘man carved out of a turnip, looking out of astonished eyes’. Despite occasional arthritic passages of modern academic discourse, Frazier’s analysis is consistently intelligent and judicious, an affectionate adjunct to Moore’s numerous self-portraits. Most biographies of writers alternately narrate and explain the circumstances behind the work. Frazier’s challenge is to separate the author from the public personae. Contemporaries who fleetingly glimpsed the man behind the mask were always puzzled. In Great Morning!, Osbert Sitwell recalled that when Moore ‘had said something that he hoped would appal everyone in the room . . . a seraphic smile would come over his face, and remain on it, imparting to it a kind of illumination of virtue, like a saint’. Despite his impish charm, rows of pews reserved for literary friends at his funeral at Golders Green Crematorium in 1933 remained empty. There was, however, a floral tribute from Joyce. Moore deserved this gesture, and ‘his place’, in Virginia Woolf’s words, ‘among the lesser immortals of our tongue’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.