One of the many excellent photographs Barry Webb has assembled shows Blunden going out to bat with Rupert Hart-Davis, in a match between Jonathan Cape and the Alden Press. That was in 1938. Blunden looks miniature, a frail determined Don Quixote with eagle nose and jaw, who had persuaded the burly Yorkshireman as they set out for the crease together not to wear batting gloves, which were unsporting. No gesture was involved, but a certain amount of quiet conviction. John Betjeman and Joan Hunter-Dunn would have approved: indeed Betjeman was a great admirer of Blunden’s poetry. His English Poems ‘was the first book by a living poet I remember saving up to buy. I learned many of his poems by heart and can still recite them with their autumn mists, summer cricket matches, sounds of church bells and recollections of 18th-century romantic poets.’

The last point has a particular accuracy. The Georgian inspiration came not from 19th but 18th-century models, Cowper, Shenstone, John Clare, with whom Blunden identified closely and helped to bring back into general appreciation. The leading characteristic of this poetry is its facility: it flows, and the relaxed naturalness with which it flows, the informal accuracy of its diction, constitute its special virtue It is rightly a popular virtue, and Wordsworth wilfully ignored its popularity when he implied that it was the kind of poetry for a cultivated taste, ‘like claret or rope-dancing’. Compared with Clare or Blunden nothing could be less natural than the way Wordsworth treats his ‘scenes and episodes from common life’. But his best have romantic drama, as Betjeman’s scenes do, or Larkin’s, and Blunden’s poetry lacks it absolutely. Any good poet can write poems to order – Eliot or Frost or Larkin with equal facility –but Blunden’s poetry, like that of many of its 18th-century models, seems written as if to order all the time. There is no inner tension, no feeling incommunicable in any other way, as there is in Eliot or Edward Thomas, or even in such an apparently frivolous squib as Betjeman’s ‘ Death in Leamington’. Housman was unexpectedly benevolent about Blunden’s poetry and helped to get him an award from the Royal Literary Fund: but he was a little dry about it in private, observing in a letter that Blunden had a gift for describing nature, and the temptation to over-use it must have been considerable. Like Leigh Hunt, with whom he identified even more than with Clare, Blunden certainly did write too much, although in both cases there was more financial need in this than temptation. Poetry produced every day could hardly give Housman’s shiver.

Blunden’s best-known poem and anthology piece comes near it.‘ Report on Experience’ begins with a most effective Eliotian part-quotation, conflating Shakespeare’s ‘When I was young (as yet I am not old)’ with the Psalmist:‘I have been young and now am old; yet I have not seen the righteous forsaken.’

I have been young, and now am not too old;

And I have seen the righteous forsaken,

His health, his honour and his quality taken.

This is not what we were formally told.

A striking opening, and very unlike Blunden. It has the syntactic touch of Pound or John Crowe Ransom, and the inter-war flavour of understated and total disillusion. The next two stanzas retain this intensity, though with less effect, for the references to the war and to betrayal in love become more conventional, and in the last stanza collapse is complete.

Say what you will, our God sees how they run.

These disillusions are his curious proving

That he loves humanity and will go on loving;

Over there are faith, life, virtue in the sun.

The poem seems to have no inner knowledge of how to end itself, and takes refuge, though with no hint of insincerity, in what is traditionally and comfortingly familiar, like pubs and country churches and village greens. The unexpected ear that had produced the first precise cadences fails with the vagueness of that ‘Over there’; and one has the feeling the poet did not realise how close he was coming to ‘Three Blind Mice’ in the first line of the last stanza.

Not surprise but familiarity is the pleasure of Blunden’s poetry, even when he was noting, as Clare would have done, some oddity in scurrying beech leaves or spring blossoms. These are never referred back to the poet, as Edward Thomas’s strange excitements would refer them: the absence of self is the real offering in Blunden’s poems. Like Ralph Hodgson, whom he knew well in Japan, he suffers from anthologies, and his poetry is best browsed through. He made great friends with Adrian Bell, the country novelist who wrote Corduroy and became the first compiler of the Times crossword. Bell had a sharp but kindly eye for the Blunden ethos and personality, remarking that there was ‘something about the little man that made every woman who met him want to protect him from everyone else’. They were apt to smother him with ‘rivalries of affection’. Certainly he was a great success with women without trying: he received their attentions with the same ease with which he composed his verse. Such a Georgian poet could not go wrong if he wrote about the right things, and in the same spirit he accepted women for their traditional qualities.

Provided they continued to show them to him. Home on leave in the first war, he met a charming and pretty barmaid who seemed to display them all. Blunden, whose father was a village schoolmaster, was no snob. But it seems that she did not really like cricket, or beer, or Charles Lamb, or – after a very brief marital idyll – Blunden himself. She declined to accompany him to Japan, for which he set out in 1924 to take up a teaching post at Tokyo University. Although his students soon began to like and appreciate him, he was lonely there, and it was not long before he was solaced by a short swarthy teacher, seven years his senior, called Aki Hayashi. Aki spoke excellent English, and made it clear she would like to accompany him back to England and marry him after he had obtained a divorce. No Madam Butterfly (his students wondered what on earth he could see in her), she was tender and kind and helpful, all that a Japanese wife could still be, and Blunden seems to have given her every encouragement. The episode has been very well presented by Sumie Okada, in a recent book on Blunden in Japan.

Aki did indeed come home with him: but once there he was temporarily reconciled with his wife Mary, and no more was said about divorce, at least not for a while. Aki was installed in a room in London and set to work on Leigh Hunt in the British Museum, where her researches were to be a great help over the years. She settled down stoically enough in her new role and never went back to Japan. Blunden supported her and was invariably kind. Short of money and full of anxieties which made his asthma bad and whisky a remedy, he turned out lectures and articles at full speed, helped by a circle of friends which included a fellow asthmatic, T.S. Eliot, who also befriended Ralph Hodgson. They took sides over the ladies – the ever tolerant Eddie Marsh facetiously exclaiming in a letter to Blunden that he had been ‘rather a pig’ – but on the whole no one blamed him: he was not the kind of person who gets the blame. What he did get was a fellowship at Merton College, Oxford (the Warden kindly advised him to do some reading over the summer in preparation for his teaching), and another lady, Sylva Norman, whose literary ambitions he assisted.

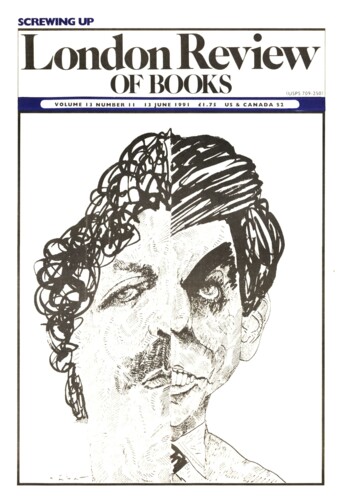

Teaching was as much a success in Oxford as it had been in Japan: he got on with his pupils and took great trouble over them. Divorced and remarried, he settled down happily, acquiring a reputation as a bit of a pacifist in the Second World War. In 1947, with yet another other wife (he remained on excellent terms with them all) he went as professor to Hong Kong University, where he was as popular as he had been everywhere else, and his final teaching years, again in Japan, were an all-time triumph. He returned to become Professor of Poetry at Oxford, but ill-health proved too great a strain, and in spite of a large and loving family (‘one more daughter than King Lear,’ he seems to have said) his years of retirement were more saddening than most. Photographs in old age, the hawk profile distorted with steroids, are deeply touching.

Apart from its virtues as a biography Barry Webb’s book gives a remarkable picture of a literary epoch, its denizens and their way of life. The Georgians had staying power: they hung on. And although with hindsight what must for convenience be called Modernism now looks to have been the outright winner, that was not how things seemed at the time. Siegfried Sassoon, who almost hero-worshipped Blunden as well as helping him with money, saw him as the epitome of the old chivalric and rural values. His poetry was widely read and far more popular than that of the Moderns. The affirmation at the end of ‘Report on Experience’ was sincere. Blunden and Sassoon were furious when Robert Graves published in 1929 Goodbye to All That. Blunden’s comments are of great significance, and deserve to be taken seriously as evidence of what men who loathed the war, and had been through a great deal of it, actually felt and continued to feel. Very few felt like Graves. Blunden saw his conduct in writing the book as a question of doing, or not doing, the right thing.‘My Colonel, who thought himself a mere “regular soldier”, was a saint without a halo. Every detail of his life would be found to answer the great question: Is this the right thing to do? ... Graves knows “all that” and knows that he saw comparatively little of the front line: it is his own conscience that he is shouting down.’

Rather interestingly, that was in a letter to his great friend and colleague in Japan, Professor Saito. But he spent an evening with Sassoon annotating their advance copy of Goodbye to All That with passionately hostile comments, and the rift in their friendship with Graves was never entirely healed. It was readers too young to have been in the war at all who chiefly responded to Graves’s autobiography, and had the post-war feelings influenced by it. Far more popular at the time was Blunden’s own memoir, Undertones of War, written in Japan and published soon after he got back, and three years before Graves’s book. It rapidly went into several editions

But Goodbye to All That won in the end, on merit: it is a far better book. Though Blunden saw more of Flanders mud, describing it, as he engagingly says, from the standpoint of ‘a youthful shepherd in a soldier’s coat’, the ‘sensitive’ writing in Undertones of War has dated and blurred. Blunden was no doubt right about his colonel, and right about how most soldiers felt, but his instinct was to pastoralise war, as his poetry had done the Home Counties. Barry Webb’s shrewd treatment brings out very well the sad contradiction that Blunden’s immense and deserved popularity as a lecturer and literary figure has failed to stand the always hard-faced test of time. He was right about so many things, though not, perhaps, about the Duke of Windsor, whose side he impulsively took at the time of the Abdication crisis.

Only for this, maybe, I write:

Distress that service rich and bright,

So willing, unpretentious, should

So soon meet such ingratitude.

But though he objected to Eliot’s comments on Keats and Shelley, he responded at once to his ‘gentlemanly simplicity’ and the ‘something of the American loneliness in his face and ways’. Larkin’s discerning eye chose for his Oxford Book of 20th Century English Verse a poem that will certainly last, ‘Lonely Love’, in which Blunden conveys deep and strong feeling for ‘unnoticeable people’ and for how they ‘make their world’. Few poets, not even Betjeman, could do this without a hint of patronage. Blunden does it perfectly – perhaps he was thinking of Aki Hayashi.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.